“People love hearing how right they are.”—Agent Stan Beeman, The Americans

Last year on Game of Thrones, Jaime Lannister raped his sister Cersei. At least that’s what he did in the scene I saw. Statements on the matter by actors Nikolaj Coster-Waldau and Lena Headey and director Alex Graves talked about two people in a deeply dysfunctional relationship having sex they knew they shouldn’t be having, not that one person was refusing to have at all. Co-writer and showrunner David Benioff appeared to disagree in an interview taped prior to the episode’s airing, before adopting total radio silence on the issue. The show’s subsequent handling of the characters, author George R.R. Martin’s comparison of the scene to its equivalent in his original books, and further discussion by the actors provided still more complicated and confounding context. We could perhaps conclude that either through communication breakdowns between the players or a failure of execution to mirror intent, the scene — rooted in complex and destructive sexual dynamics between two habitually secretive and duplicitous characters and interpreted by half a dozen artists each with their own ideas about the event — simply got away from them.

Few of us did. Fans of the books lambasted the scene as yet another horrendous, story-destroying decision by Benioff and his creative partner Dan Weiss, two people frequent treated as singularly unsuited to the task of adaptation. Admirers of Jaime bemoaned the damage done to him by the event at least as much as his sister, the victim. Critics saw the scene as a romanticization of rape, using the show’s long and contentious history with female nudity, sex, and sexual assault to support the argument. And while the wider world focused in the latter of these three critiques, the former two were no less self-assured or severe in their respective corners of the critical firmament.

On one level, the reaction to what happened between the Siblings Lannister in the Great Sept of Baelor is just a standout example of the golden rule of arguing on the Internet: interpret with minimum good faith, attack with maximum rhetorical force. But that rule applies to discussions of everything from politics to fly fishing. In terms of art and art criticism, something else is going on—a phenomenon of which the social-justice framework for criticism is just the most well-publicized, hotly debated embodiment.

The past decade-plus has been a time of dispiriting uncertainty and powerlessness: an era of endless war, economic erosion, class disconnection, and political disillusion. At the same time, our approach to art and entertainment has become all the more unequivocal in its assertions about content and quality. We pore over TV shows for clues about their outcome, which we present with power-point precision. We treat all art like editorial cartoons, interpreting it the way we would a drawing of a fatcat politician holding bulging moneybags in each hand, and accept or reject the story accordingly. We treat the comics and novels that form the basis for our blockbusters as holy writ, we insist that fiction hew inerrantly to the facts that inspired it, and we punish those who stray from the path. We elevate our favorite characters and relationships to the point where the stories they inhabit are mere vehicles to get them to the place we’d like to see them go.

In all four cases—the Theorists, the Activists, the Purists, and the Partisans—we’re treating the inherently subjective fields of art and art criticism as things we can be objectively right about. We’re taking work that’s complex and capable of conveying multiple contradictory meanings and reducing it to a simple either/or, yes/no proposition.

In other words, we’re fucking up.

THE THEORISTS

Do Mad Men’s promo posters contain hidden clues about the fate of Don Draper? Do casting changes indicate that one major Game of Thrones character is secretly another character who hasn’t even been mentioned on the show yet? Was the Breaking Bad finale a fantasy constructed in Walter White’s post-mortem, proverbial snow globe? In a word, no. But feverish theorizing—meticulously assembled from “clues” of every conceivable sort, both on-screen and off, and long a core component of fan discussion—is increasingly common among professional critics as well. Just ask Diana the waitress.

This addiction to over-interpretation and augury can be traced back, at least in its television manifestation, to Lost. A blockbuster hit woven together from overlapping, intertwining, occasionally contradictory mysteries, it invited viewers to figure it out like few shows before it. Remember the essay-length “reviews” EW’s Jeff “Doc” Jensen would crank out every week, each one stuffed with elaborate theories that would be immediately superseded by the next episode? The focus on unraveling and reconstructing the show’s mythos gave it an undeserved reputation for being dizzying to follow; this was true only if you spent most of your viewing time ignoring what was on screen in favor of what was bubbling in your brain. The pleasures of the show — some simple and pulpy, like the gorgeous cast, rollicking fight scenes, and super-scary horror elements; some complex and moving, like the devolution of its leading men Jack Shepherd and John Locke into bitter failures — got lost in the shuffle.

The Theorists are ideal critics and consumers in one respect, at least: They’re always looking ahead. The pop-culture-coverage content mill’s business model depends not on art itself, but on anticipation of art to come. The endless stream of teasers, trailers, casting news, set photos, post-credits stingers, and so on fuels a mentality wherein What Happens Next? is the only question worth asking. If prediction is the TV-crit industry’s product, the Theorists are simply seizing the means of production.

But Theorists work backwards as well, looking back, digging in, and asserting what “really” happened in the art they’ve already experienced. The “Definitive Explanation” of the end of The Sopranos by an anonymous blogger is the most famous example, with its conclusions affecting even how journalists interview the show’s creator. Ambiguity, deliberate or otherwise, has no place in such analyses.

To the Theorists, art is a puzzle to be assembled, a code to be cracked. To be blunt, they’re missing the goddamn point. Like a completed crossword puzzle, stories that can be “figured out” can be set aside afterwards, with the solver content that she’s gotten everything she can out of the experience. Great art endures and evolves. It cannot be solved.

THE ACTIVISTS

Like a Rorschach blot, the acronym “SJW” reveals a great deal in how people react to it. Pejoratively applied—by conservatives, libertarians, anti-feminists, anything-goes speech advocates—it’s intended to deride the Social Justice Warriors for whom it stands as arrogant, intolerant keyboard commandos. According to this line of reasoning, SJWs inflict their personal political shibboleths on art that must be allowed to take risks, make mistakes, and commit sins—if, indeed, these mistakes and sins are even recognized as such by their defenders. More often, SJWs are ridiculed for complaining when there’s absolutely nothing wrong with the work in question at all, according to those who enjoy it.

Self-applied, however, “SJW” reclaims a term of mockery and turns it into a badge of honor. As far as going to proverbial war is concerned, the argument goes, social justice is as good a causus belli as it gets. For far too long, art considered ideologically neutral has invisibly enforced vast disparities between races, religions, classes, genders, sexual orientations, and abilities, using artistic exploration or entertainment value as a fig leaf for its excesses. In that light, it’s fair play, and high time, for marginalized voices to take the mic and call out problematic work, while calling for work that does better.

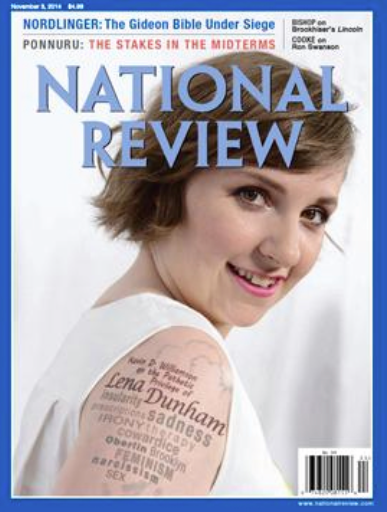

SJWs are the most prominent example of the Activists: critics who apply sociopolitical metrics to determine the worth of a work of art. But for every Activist, there is of course an equal and opposite Reactivist, and their contributions to this overarching approach must not be overlooked. Are the anti-SJWs any less intolerant, any more forgiving of divergent views? Begging your pardon, fuck no. Conservative cultural criticism is as rife with shoe-on-the-table we-will-bury-you rhetoric as the most vociferous left-wing jeremiad: Look no further than National Review’s risible assault on Lena Dunham to see just how personal the political can get.

Moreover, right-wing culture critics are punching down from positions of cultural privilege and power. The nadir here is GamerGate: A reaction to the emergence of prominent, progressive, vocal, female game designers and critics, this movement has employed pervasive bullying tactics to shame and silence them. As such, it’s Nerd Culture’s first genuine outbreak of the real and rhetorical violence that mainstream-culture kids have employed against geeks in middle schools since time immemorial.

The two tribes of Activists are positionally as well as ideologically distinct. Culture, like academia, is one of the few spheres of public life where the right is actually at a disadvantage, so reactionary critics often treat the producers and products of art as an enemy camp. On the other hand, progressive cultural criticism is in essence a form of self-policing, a purity test applied to ostensible allies. (A less charitable read would be that it’s easier to score points on your own goal.) But the methodology is identical. Art and artist are conflated into one entity that says only one thing, and you’re either with it or against it. You’re left with “Why David Benioff and D.B. Weiss Raped Cersei Lannister.”

Alyssa Rosenberg, the most nuanced, least predictable critic addressing art in through this lens, nailed its excesses in a piece with the provocative title ‘What liberal culture critics have in common with Ted Cruz,” written after the Texas Senator, Republican presidential hopeful, and jingoistic buffoon publicly claimed to have sworn off rock music for country after finding rock’s response to 9/11 wanting. “If Cruz has erred,” Rosenberg writes, “he’s made a mistake that some on the extreme opposite of the political spectrum share as well: trying to fit culture neatly into established cultural positions, rather than embracing art’s power to transcend them.” To the Activists, transcendence is not in art’s remit. A work says exactly what it says, no more and no less, and can be judged, embraced, or rejected accordingly, as can the artist who made it. Critic Ken Parille has dubbed this mentality Millennial Literalism, referring to the perceived age group of many of its adherents, but don’t let the M-word reduce the point being made to the quintillionth “what’s the matter with kids today” argument made since the dawn of time. Audiences of every age and political persuasion flatten art’s multivalent magic into something easier to handle—and far less worthwhile as a result.

THE PURISTS

From millennial literalists to Biblical literalists, or in this case, biblical with a lowercase “b.” Of our four groups, the Purists are perhaps the best situated for claiming to be objectively correct about art using their metric of choice: All they have to do is open a book. An adaptation’s fidelity to its source material is their primary concern—an increasingly common one, given the pop-cultural primacy of Game of Thrones, 50 Shades of Grey, the Marvel Cinematic Universe, and other works drawn from preexisting, massively popular, widely accessible texts. If the adaptation deviates, it’s doing something wrong, and chapter-and-verse citations from the original may be proffered as evidence. Time’s James Poniewozik summed the mentality up in four words: “The Book Was Better.”

It shouldn’t surprise us that the Purists are primarily fans of genre stories — fantasy, science fiction, superhero comics, pornographic fanfiction. Yes, nerd culture has taken over mainstream culture almost entirely (sports will always be the great exception to geek hegemony). But as O’Brien asserts to Winston in 1984, an increase in power by the ruling class drives it to become more, not less, intolerant of dissent. Purists demand respect above all else, and filmmaker fealty to the fictions that have shaped their reality is a must. I wish I could remember who joked to me that Kenneth Branagh had more leeway to reinterpret Hamlet than he did with Thor, but that’s about the size of it.

The nerds’ close cousins, the wonks, are a vital and growing constituency for the Purist ranks, as seen in the explosion of “What [Title] Gets Wrong About [Topic]” thinkpieces that crop up in the wake of every New Big Thing. Here, the source material is not a copy of A Feast for Crows or Outlander, but the real world itself. Science fiction films are judged harshly for shaky science, romantic fantasies are criticized for failing to reflect sexual realities, et cetera. But fiction and fantasies deviate from fact by definition—that’s what makes them fiction and fantasies. A reflexive mental addition of “What This Article Gets Wrong About Narrative Art” as a subtitle for every piece that follows that formula is a must for the informed reader.

Source-material fundamentalists, meanwhile, would do well to ask themselves if Francis Ford Coppola’s The Godfather is a poorer film because crooner Johnny Fontane lost the main-character status he had in Mario Puzo’s book, or if Steven Spielberg’s Jaws would have been improved had author Peter Benchley’s subplots involving the Richard Dreyfus character coming on to Chief Brody’s wife, or the mafia killing Brody’s cat in front of his kid, stayed intact. Different storytelling mediums have different needs, and moreover the people responsible for translating a work from one such medium to another can and should have ideas of their own. Change is a morally neutral phenomenon. The mere fact of change doesn’t inherently indicate anything about the quality of the adaptation, or the character of the artist responsible for it.

THE PARTISANS

The post-blog, post-social-media explosion of pop-cultural community and comment on the Internet has given rise to fan subgroups with highly specialized interests regarding the art they consume, and each such subgroup has its own cutesy nickname. Shippers pull for specific romantic relationships—some that actually exist in the story, some that are hoped for, others that are functionally impossible—between characters. Stans, like their real-person-superfan equivalents, celebrate their favorite characters, often with near-religious (if self-aware) fervor, and dislike those perceived as rivals. Bad Fans (male and female editions) lionize flawed, antiheroic, or straight-up villainous characters, excusing or even endorsing their bad behavior and attacking characters (and actors!) who call them out.

Whether these Partisans congregate on tumblr, deviantArt, fanfic message boards, or the comment threads on any mainstream-media Breaking Bad recap, the view of art from where they’re sitting is crystal clear: A work succeeds when it does right by their flawless fave and fails when it doesn’t. The Partisans often locate that failure in the hearts and souls of showrunners, who in their perceived mishandling of the issue at hand reveal hidden hatred for the very characters and relationships it is their job to shepherd.

The real failure here, though, is one of audience empathy with the artist. All of us have characters we love, hook-ups we wish could happen, and moments of vicarious delight over dirty deeds. But when we run art primarily or exclusively through these personal filters, we lose our shot at experiencing the ideas and emotions of another person, the artist — one of the great gifts art gives us. We insist that art accommodates our headspace, rather than embracing the tiny transcendence of leaving ourselves behind and meeting art where it lives.

That’s not necessarily exactly where the artist wants it to be, mind you. Partisans of authorial intent über alles are just as misguided as their counterparts, in that the expressed opinion of a work’s creator regarding her goals is not the final word on her creation’s effect and value. Art exists in the ineffable space between artist an audience, in the interaction between the artist’s ideas, their execution of those ideas in the work, and the audience’s reception of the work, itself shaped and fueled by ideas of their own. Far too many variables are at play for either the artist or the audience to ever find firm ground. Art is a leap of faith.

And you simply can’t make that leap if you’re sure where you’re gonna land. Theorists, Activists, Purists, and Partisans are all searching for a way to feel confident that art can be right or wrong; that the artists who make it are in turn right or wrong, and can be praised or condemned accordingly; and that you, the critic, can be right or wrong and praised or condemned in turn. Each approach has its benefits—in particular I believe all art is political and must be considered and addressed as such. And in an era of crushing anxiety, the certainty offered by each approach is a reassuring lure. But each approach is ultimately reductive and, if no further steps to interrogate the work and one’s feelings about it are taken, contrary to what art and criticism are. Art is big and messy. Making it, consuming it, talking about it—these are inherently risky propositions.

If we’re ever to do anything worthwhile with it, the risk must be embraced.