Railroads were, in theory, an attractive business: while they cost a lot to build, once built, the marginal cost of carrying additional goods was extremely low; sure, you needed to actually run a train, which need fuel and workers and which depreciated the equipment involved, but those costs were minimal compared to the revenue that could be earned from carrying goods for customers that had to pay to gain access to the national market unlocked by said railroads.

The problem for railroad entrepreneurs in the 19th century is that they were legion: as locomotion technology advanced and became standardized, and steel production became a massive industry in its own right, fierce competition arose to tie the sprawling United States together. This was a problem for those seemingly attractive railroad economics: sure, marginal costs were low, but that meant a race to the bottom in terms of pricing (which is based on covering marginal costs, ergo, low marginal costs mean a low floor in terms of the market clearing price). It was the investors in railroads — the ones who paid the upfront cost of building the tracks in the hope of large profits on low marginal cost service, and who were often competing for (and ultimately with) government land grants and subsidies, further fueling the boom — that were left holding the bag.

This story, like so many technological revolutions, culminated in a crash, in this case the Panic of 1873. The triggering factor for the Panic of 1873 was actually currency, as the U.S. responded to a German decision to no longer mint silver coins by changing its policy of backing the U.S. dollar with both silver and gold to gold only, which dramatically tightened the money supply, leading to a steep rise in interest rates. This was a big problem for railway financiers who could no longer service their debts; their bankruptcies led to a slew of failed banks and even the temporary closure of the New York Stock Exchange, which rippled through the economy, leading to a multi-year depression and the failure of over 100 railroads within the following year.

Meanwhile, oil, then used primarily to refine kerosene for lighting, was discovered in Titusville, Pennsylvania in 1859, Bradford, Pennsylvania in 1871, and Lima, Ohio in 1885. The most efficient refineries in the world, thanks to both vertical integration and innovative product creation using waste products from the kerosene refinement process, including the novel use of gasoline as a power source, were run by John D. Rockefeller in Cleveland. Rockefeller’s efficiencies led to a massive boom in demand for kerosene lighting, that Rockefeller was determined to meet; his price advantage — driven by innovation — allowed him to undercut competitors, forcing them to sell to Rockefeller, who would then increase their efficiency, furthering the supply of cheap kerosene, which drove even more demand.

This entire process entailed moving a lot of products around in bulk: oil needed to be shipped to refineries, and kerosene to burgeoning cities through the Midwest and east coast. This was a godsend to the struggling railroad industry: instead of struggling to fill trains from small-scale and sporadic shippers, they signed long-term contracts with Standard Oil; guaranteed oil transportation covered marginal costs, freeing up the railroads to charge higher profit-making rates on those small-scale and sporadic shippers. Those contracts, in turn, gave Standard Oil a durable price advantage in terms of kerosene: having bought up the entire Ohio refining industry through a price advantage earned through innovation and efficiency, Standard Oil was now in a position to do the same to the entire country through a price advantage gained through contracts with railroad companies.

The Sherman Antitrust Act

There were, to be clear, massive consumer benefits to Rockefeller’s actions: Standard Oil, more than any other entity, brought literal light to the masses, even if the masses didn’t fully understand the ways in which they benefited from Rockefeller’s machinations; it was the people who understood the costs — particularly the small businesses and farmers of the Midwest generally, and Ohio in particular — who raised a ruckus. They were the “small-scale and sporadic shippers” I referenced above, and the fact that they had to pay far more for railroad transportation in a Standard Oil world than they had in the previous period of speculation and over-investment caught the attention of politicians, particularly Senator John Sherman of Ohio.

Senator Sherman had not previously shown a huge amount of interest in the issue of monopoly and trusts, but he did have oft-defeated presidential aspirations, and seized on the discontent with Standard Oil and the railroads to revive a bill originally authored by a Vermont Senator named George Edmunds; the relevant sections of the Sherman Antitrust Act were short and sweet and targeted squarely at Standard Oil’s contractual machinations:

Sec. 1. Every contract, combination in the form of trust or otherwise, or conspiracy, in restraint of trade or commerce among the several States, or with foreign nations, is hereby declared to be illegal. Every person who shall make any such contract or engage in any such combination or conspiracy, shall be deemed guilty of a misdemeanor, and, on conviction thereof, shall be punished by fine not exceeding five thousand dollars, or by imprisonment not exceeding one year, or by both said punishments, at the discretion of the court.

Sec. 2. Every person who shall monopolize, or attempt to monopolize, or combine or conspire with any other person or persons, to monopolize any part of the trade or commerce among the several States, or with foreign nations, shall be deemed guilty of a misdemeanor, and, on conviction thereof; shall be punished by fine not exceeding five thousand dollars, or by imprisonment not exceeding one year, or by both said punishments, in the discretion of the court.

And so we arrive at Google.

The Google Case

Yesterday, from the Wall Street Journal:

A federal judge ruled that Google engaged in illegal practices to preserve its search engine monopoly, delivering a major antitrust victory to the Justice Department in its effort to rein in Silicon Valley technology giants. Google, which performs about 90% of the world’s internet searches, exploited its market dominance to stomp out competitors, U.S. District Judge Amit P. Mehta in Washington, D.C. said in the long-awaited ruling.

“Google is a monopolist, and it has acted as one to maintain its monopoly,” Mehta wrote in his 276-page decision released Monday, in which he also faulted the company for destroying internal messages that could have been useful in the case. Mehta agreed with the central argument made by the Justice Department and 38 states and territories that Google suppressed competition by paying billions of dollars to operators of web browsers and phone manufacturers to be their default search engine. That allowed the company to maintain a dominant position in the sponsored text advertising that accompanies search results, Mehta said.

While there have been a number of antitrust laws passed by Congress, most notably the Clayton Antitrust Act of 1914 and Federal Trade Commission Act of 1914, the Google case is directly downstream of the Sherman Act, specifically Section 2, and its associated jurisprudence. Judge Mehta wrote in his 286-page opinion:

“Section 2 of the Sherman Act makes it unlawful for a firm to ‘monopolize.’” United States v. Microsoft, 253 F.3d 34, 50 (D.C. Cir. 2001) (citing 15 U.S.C. § 2). The offense of monopolization requires proof of two elements: “(1) the possession of monopoly power in the relevant market and (2) the willful acquisition or maintenance of that power as distinguished from growth or development as a consequence of a superior product, business acumen, or historic accident.” United States v. Grinnell Corp., 384 U.S. 563, 570–71 (1966).

Note that Microsoft reference: the 1990s antitrust case provides the analytical framework Mehta used in this case.

The court structures its conclusions of law consistent with Microsoft’s analytical framework. After first summarizing the principles governing market definition, infra Section II.A, the court in Section II.B addresses whether general search services is a relevant product market, and finding that it is, then evaluates in Section II.C whether Google has monopoly power in that market. In Part III, the court considers the three proposed advertiser-side markets. The court finds that Plaintiffs have established two relevant markets — search advertising and general search text advertising — but that Google possesses monopoly power only in the narrower market for general search text advertising. All parties agree that the relevant geographic market is the United States.

The court then determines whether Google has engaged in exclusionary conduct in the relevant product markets. Plaintiffs’ primary theory centers on Google’s distribution agreements with browser developers, OEMs, and carriers. The court first addresses in Part IV whether the distribution agreements are exclusive under Microsoft. Finding that they are, the court then analyzes in Parts V and VI whether the contracts have anticompetitive effects and procompetitive justifications in each market. For reasons that will become evident, the court does not reach the balancing of anticompetitive effects and procompetitive justifications. Ultimately, the court concludes that Google’s exclusive distribution agreements have contributed to Google’s maintenance of its monopoly power in two relevant markets: general search services and general search text advertising.

I find Mehta’s opinion well-written and exhaustive, but the decision is ultimately as simple as the Sherman Act: Google acquired a monopoly in search through innovation, but having achieved a monopoly, it is forbidden from extending that monopoly through the use of contractual arrangements like the default search deals it has with browser developers, device makers, and carriers. That’s it!

Aggregators and Contracts

To me this simplicity is the key to the case, and why I argued from the get-go that the Department of Justice was taking a far more rational approach to prosecuting a big tech monopoly than the FTC or European Commission had been. From a 2020 Stratechery Article entitled United States v. Google:

The problem with the vast majority of antitrust complaints about big tech generally, and online services specifically, is that Page is right [about competition only being a click away]. You may only have one choice of cable company or phone service or any number of physical goods and real-world services, but on the Internet everything is just zero marginal bits.

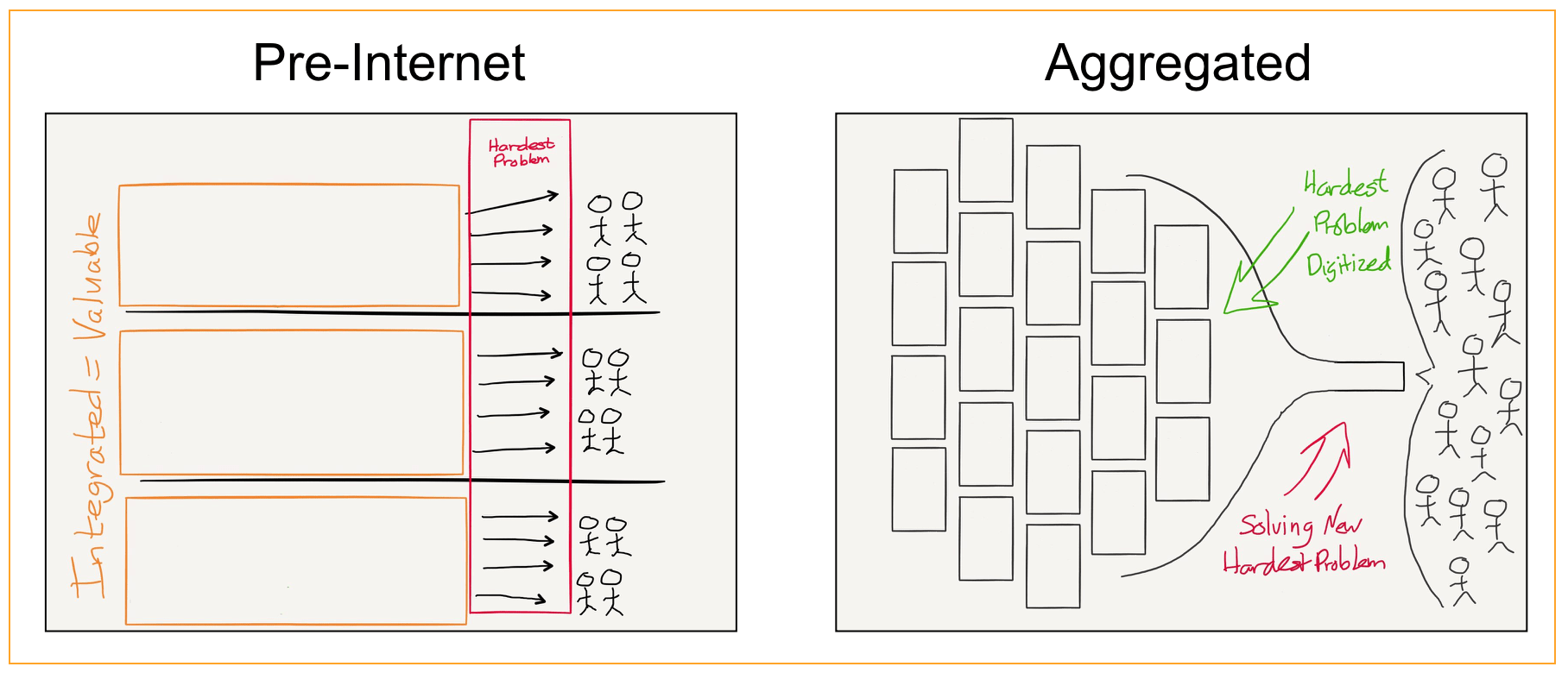

That, though, means there is an abundance of data, and Google helps consumers manage that abundance better than anyone. This, in turn, leads Google’s suppliers to work to make Google better — what is SEO but a collective effort by basically the entire Internet to ensure that Google’s search engine is as good as possible? — which attracts more consumers, which drives suppliers to work even harder in a virtuous cycle. Meanwhile, Google is collecting information from all of those consumers, particularly what results they click on for which searches, to continuously hone its accuracy and relevance, making the product that much better, attracting that many more end users, in another virtuous cycle:

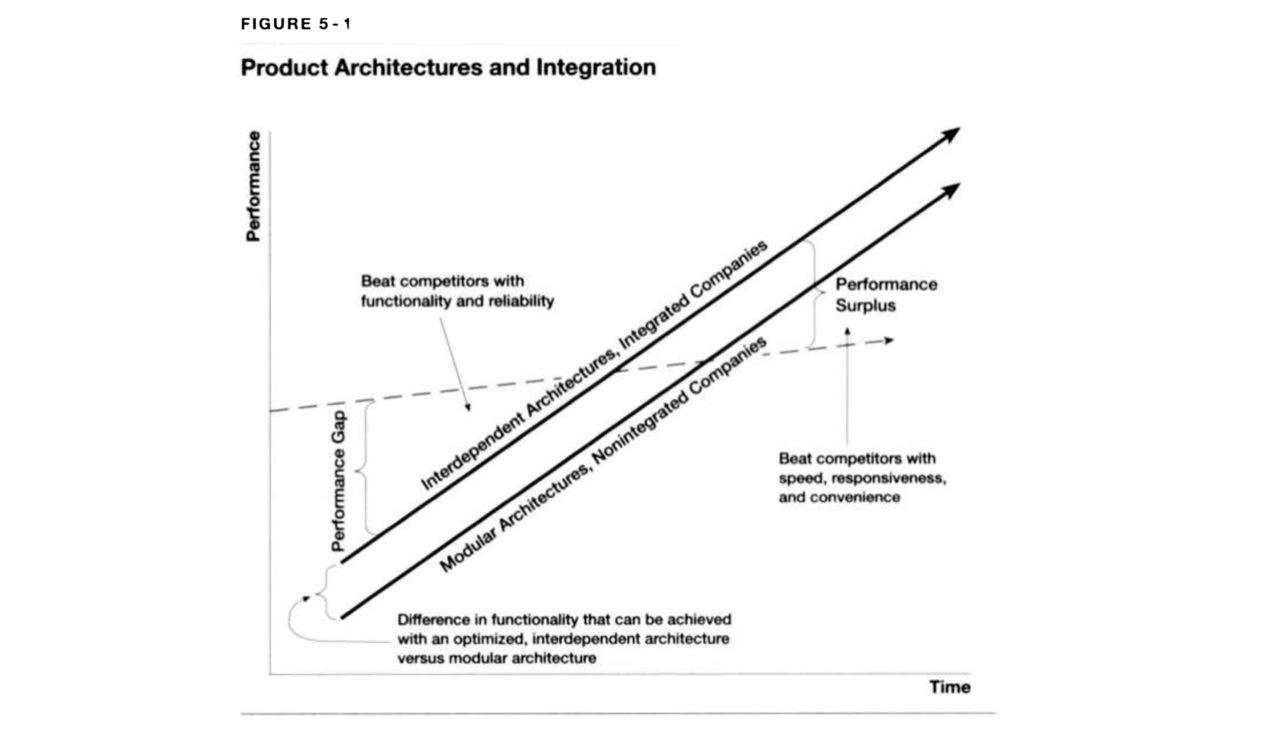

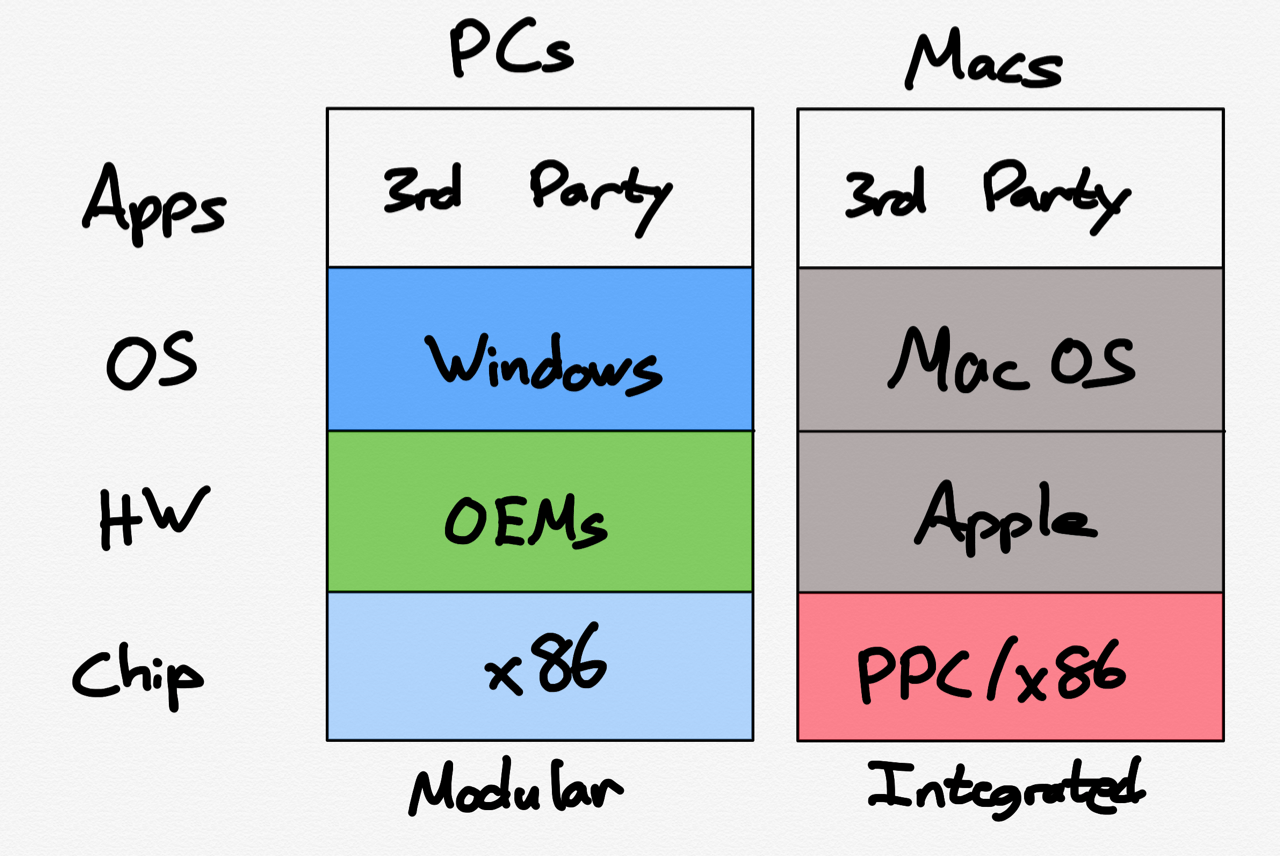

One of the central ongoing projects of this site has been to argue that this phenomenon, which I call Aggregation Theory, is endemic to digital markets…In short, increased digitization leads to increased centralization (the opposite of what many originally assumed about the Internet). It also provides a lot of consumer benefit — again, Aggregators win by building ever better products for consumers — which is why Aggregators are broadly popular in a way that traditional monopolists are not…

The solution, to be clear, is not simply throwing one’s hands up in the air and despairing that nothing can be done. It is nearly impossible to break up an Aggregator’s virtuous cycle once it is spinning, both because there isn’t a good legal case to do so (again, consumers are benefitting!), and because the cycle itself is so strong. What regulators can do, though, is prevent Aggregators from artificially enhancing their natural advantages…

That is exactly what this case was about:

This is exactly why I am so pleased to see how narrowly focused the Justice Department’s lawsuit is: instead of trying to argue that Google should not make search results better, the Justice Department is arguing that Google, given its inherent advantages as a monopoly, should have to win on the merits of its product, not the inevitably larger size of its revenue share agreements. In other words, Google can enjoy the natural fruits of being an Aggregator, it just can’t use artificial means — in this case contracts — to extend that inherent advantage.

I laid out these principles in 2019’s A Framework for Regulating Competition on the Internet, and it was this framework that led me to support the DOJ’s case initially, and applaud Judge Mehta’s decision today.

Mehta’s decision, though, is only about liability: now comes the question of remedies, and the truly difficult questions for me and my frameworks.

Friendly Google

The reason to start this Article with railroads and Rockefeller and the history of the Sherman Antitrust Act is not simply to provide context for this case; rather, it’s important to understand that antitrust is inherently political, which is another way of saying it’s not some sort of morality play with clearly distinguishable heroes and villains. In the case of Standard Oil, the ultimate dispute was between the small business owners and farmers of the Midwest and city dwellers who could light their homes thanks to cheap kerosene. To assume that Rockefeller was nothing but a villain is to deny the ways in which his drive for efficiency created entirely new markets that resulted in large amounts of consumer welfare; moreover, there is an argument that Standard Oil actually benefited its political enemies as well, by stabilizing and standardizing the railroad industry that they ultimately resented paying for.

Indeed, there are some who argue, even today, that all of antitrust law is misguided, because like all centralized interference in markets, it fails to properly balance the costs and benefits of interference with those markets. To go back to the Standard Oil example, those who benefited from cheap kerosene were not politically motivated to defend Rockefeller, but their welfare was in fact properly weighed by the market forces that resulted in Rockefeller’s dominance. Ultimately, though, this is a theoretical argument, because politics do matter, and Sherman tapped into a deep and longstanding discomfort in American society with dominant entities like Standard Oil then, and Google today; that’s why the Sherman Antitrust Act passed by a vote of 51-1 in the Senate, and 242-0 in the House.

Then something funny happened: Standard Oil was indeed prosecuted under the Sherman Antitrust Act, and ordered to be broken up into 34 distinct companies; Rockefeller had long since retired from active management at that point, but still owned 25% of the company, and thus 25% of the post-breakup companies. Those companies, once listed, ended up being worth double what they were as Standard Oil; Rockefeller ended up richer than ever. Moreover, it was those companies, like Exxon, that ended up driving a massive increase in oil by expanding from refining to exploration all over the world.

The drivers of that paradox are evident in the consideration of remedies for Google. One possibility is a European Commission-style search engine choice screen for consumers setting up new browsers or devices: is there any doubt that the vast majority of people will choose Google, meaning Google keeps its share and gets to keep the money it gives Apple and everyone else? Another is that Google is barred from bidding for default placement, but other search engines can: that will put entities like Apple in the uncomfortable position of either setting what it considers the best search engine as the default, and making no money for doing so, or prioritizing a revenue share from an also-ran like Bing — and potentially seeing customers go to Google anyways. The iPhone maker could even go so far as to build its own search engine, and seek to profit directly from the search results driven by its distribution advantage, but that entails tremendous risk and expense on the part of the iPhone maker, and potentially favors Android.

That, though, was the point: the cleverness of Google’s strategy was their focus on making friends instead of enemies, thus motivating Apple in particular to not even try. I told Michael Nathanson and Craig Moffett when asked in a recent interview why Apple doesn’t build a search engine:

Apple already has a partnership with Google, the Google-Apple partnership is really just a beautiful manifestation of how, don’t-call-them-monopolies, can really scratch each other’s back in a favorable way, such that Google search makes up something like 17% or 20% of Apple’s profit, it’s basically pure profit for Apple and people always talk about, “When’s Apple going to make a search engine?” — the answer is never. Why would they? They get the best search engine, they get profits from that search engine without having to drop a dime of investment, they get to maintain their privacy brand and say bad things about data-driven advertising, while basically getting paid by what they claim to hate, because Google is just laundering it for them. Google meanwhile gets the scale, there’s no points of entry for potential competition, it makes total sense.

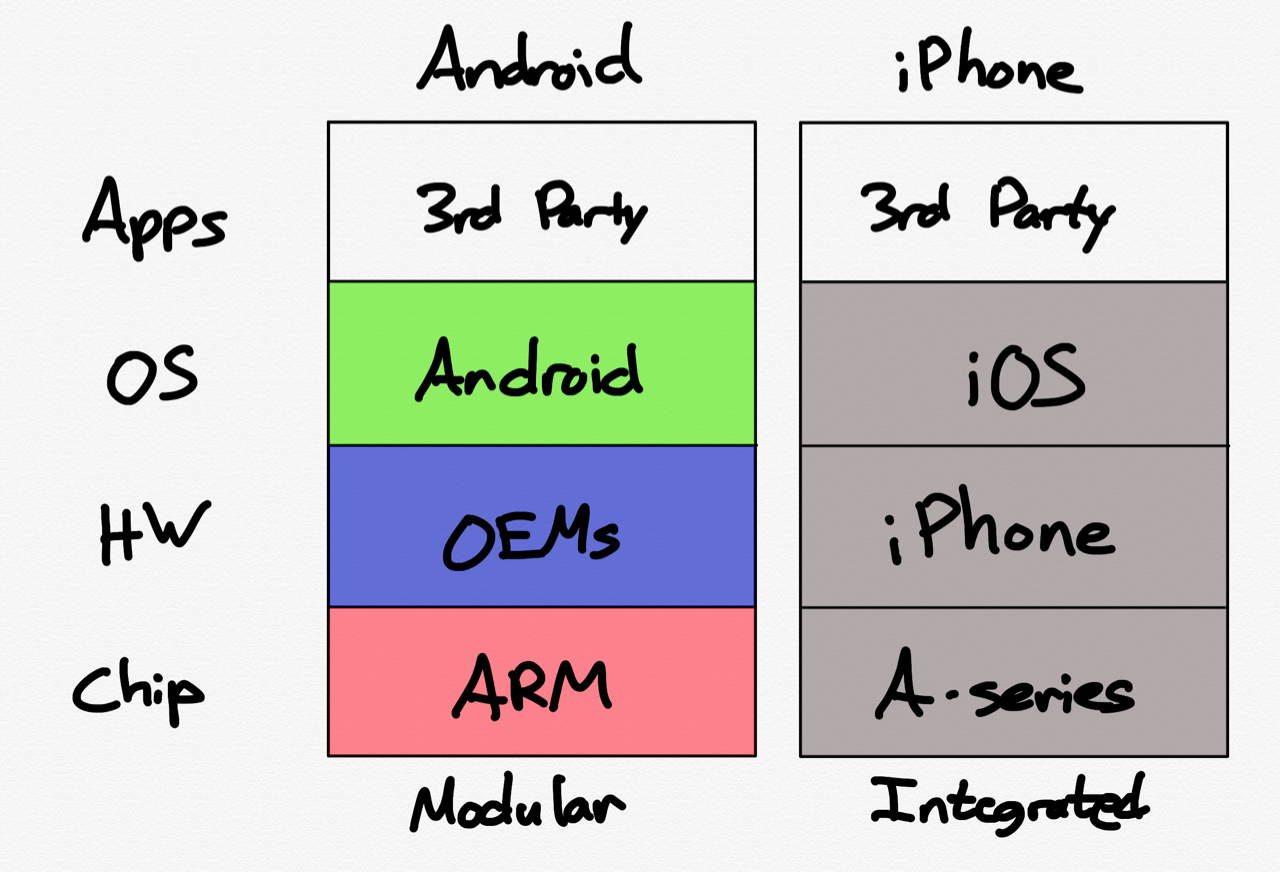

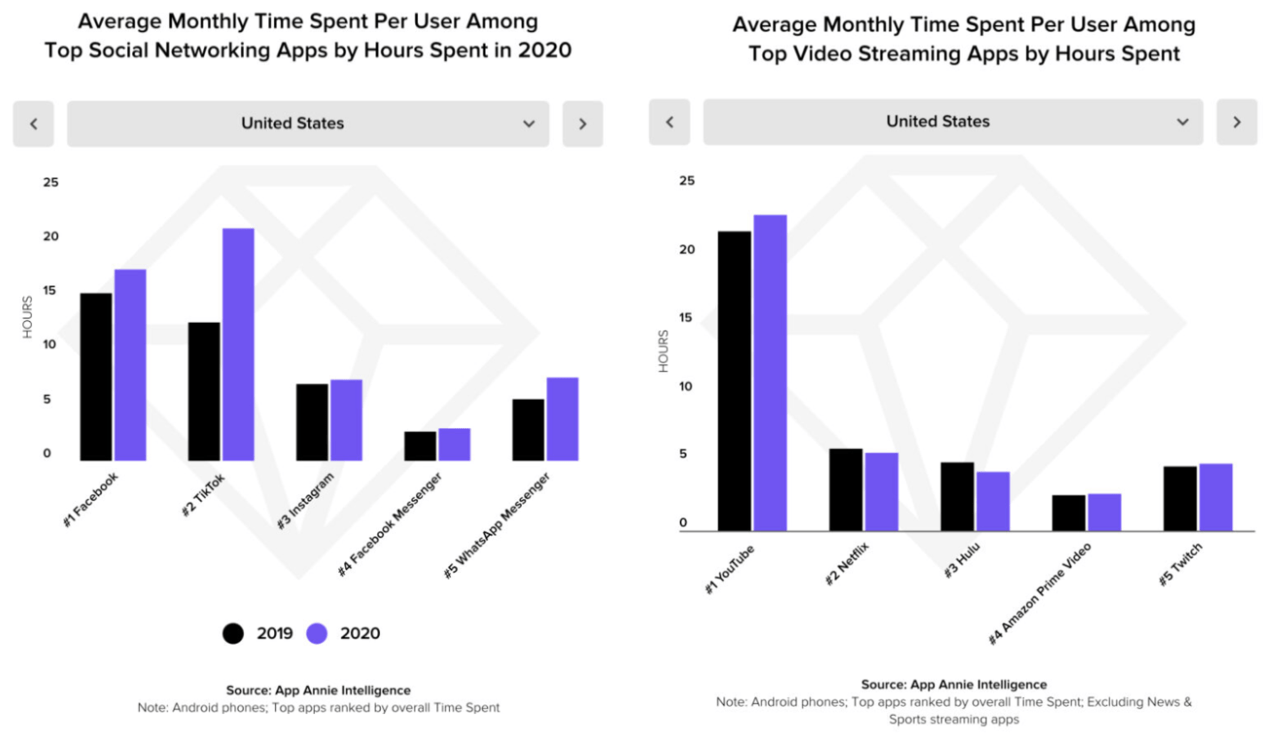

This wasn’t always Google’s approach; in the early years of the smartphone era the company had designs on Android surpassing the iPhone, and it was a whole-company effort. That, mistakenly in my view, at least from a business perspective, meant using Google’s services — specifically Google Maps — to differentiate Android, including shipping turn-by-turn directions on Android only, and demanding huge amounts of user data from Apple to maintain an inferior product for the iPhone.

Apple’s response was shocking at the time: the company would build its own Maps product, even though that meant short term embarrassment. It was also effective, as evidenced by testimony in this case. From Bloomberg last fall:

Two years after Apple Inc. dropped Google Maps as its default service on iPhones in favor of its own app, Google had regained only 40% of the mobile traffic it used to have on its mapping service, a Google executive testified in the antitrust trial against the Alphabet Inc. company. Michael Roszak, Google’s vice president for finance, said Tuesday that the company used the Apple Maps switch as “a data point” when modeling what might happen if the iPhone maker replaced Google’s search engine as the default on Apple’s Safari browser.

The lesson Google learned was that Apple’s distribution advantages mattered a lot, which by extension meant it was better to be Apple’s friend than its enemy. I wrote in an Update after that revelation:

This does raise a question I get frequently: how can I argue that Google wins by being better when it is willing to pay for default status? I articulated the answer on a recent episode of Sharp Tech, but briefly, nothing exists in a vacuum: defaults do matter, and that absolutely impacts how much better you have to be to force a switch. In this case Google took the possibility off of the table completely, and it was a pretty rational decision in my mind.

It also, without question, reduced competition in the space, which is why I always thought this was a case worth taking to court. This is in fact a case where I think even a loss is worthwhile, because I find contracts between Aggregators to be particularly problematic. Ultimately, though, my objection to this arrangement is just as much, if not more, about Apple and its power. They are the ones with the power to set the defaults, and they are the ones taking the money instead of competing; it’s hard to fault Google for being willing to pay up.

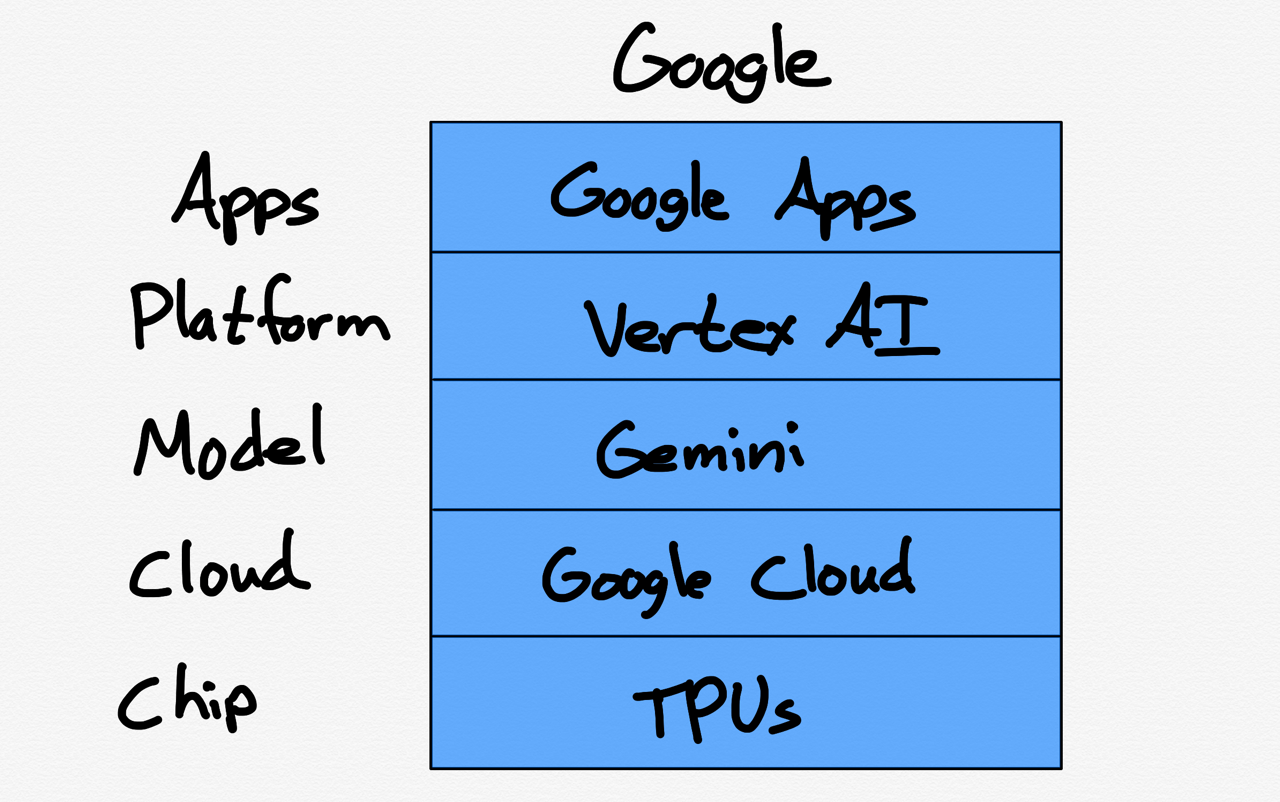

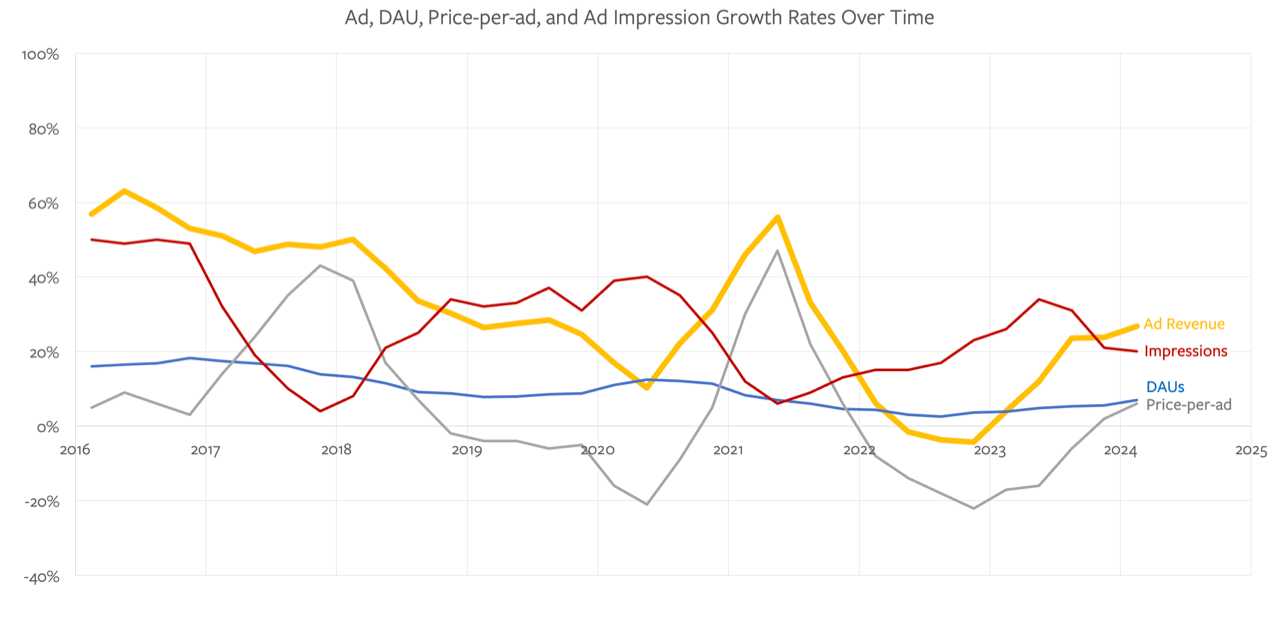

Tech companies, particularly advertising-based ones, famously generate huge amounts of consumer surplus. Yes, Google makes a lot of money showing you ads, but even at a $300+ billion run rate, the company is surely generating far more value for consumers than it is capturing. That is in itself some degree of defense for the company, I should note, much as Standard Oil brought light to every level of society; what is notable about these contractual agreements, though, is how Google has been generating surplus for everyone else in the tech industry.

Maybe this is a good thing; it’s certainly good for Mozilla, which gets around 80% of its revenue from its Google deal. It has been good for device makers, commoditized by Android, who have an opportunity for scraps of profit. It has certainly been profitable for Apple, which has seen its high-margin services revenue skyrocket, thanks in part to the ~$20 billion per year of pure profit it gets from Google without needing to make any level of commensurate investment.

Enemy Remedies

However, has it been good for Google, not just in terms of the traffic acquisition costs it pays out, but also in terms of the company’s maintenance of the drive that gave it its dominant position in the first place? It’s a lot easier to pay off your would-be competitors than it is to innovate. I’m hesitant to say that antitrust is good for its subjects, but Google does make you wonder.

Most importantly, has it been good for consumers? This is where the Apple Maps example looms large: Apple has shown it can compete with Google if it puts resources behind a project it considers core to the iPhone experience. By extension, the entire reason why Google favored Google Maps in the first place, leaving Apple no choice but to compete, is because they were seeking to advantage Android relative to the iPhone. Both competitions drove large amounts of consumer benefit that continue to persist today.

I would also note that the behavior I am calling for — more innovation and competition, not just from Google’s competitors, but Google itself — is the exact opposite of what the European Union is pushing for, which is product stasis. I think the E.U. is mistaken for the exact same reasons I think Judge Mehta is right.

There’s also the political point: I am an American, and I share the societal sense of discomfort in dominant entities that made the Sherman Antitrust Act law in the first place; yes, it’s possible this decision doesn’t mean much in the end, but it’s pushing in a direction that is worth leaning into

This is why, ultimately, I am comfortable with the implications of my framework, and why I think the answer to the remedy question is an injunction against Google making any sort of payments or revenue share for search; if you’re a monopoly you don’t get to extend your advantage with contracts, period (now do most-favored nation clauses). More broadly, we tend to think of monopolies as being mean; the problem with Aggregators is they have the temptation to be too nice. It has been very profitable to be Google’s friend; I think consumers — and Google — are better off if the company has a few more enemies.

I wrote a follow-up to this Article in this Daily Update.