Phyllis Yvonne Stickney wouldn’t put up with it – not for one minute. If a child were murdered on her street, she would not stay silent the way the neighbors do in the play she is directing at Penn.

“If I had been on that block, I would have had something to say,” said Stickney, an actor, comedian, playwright, activist, and former Philadelphian who is directing the Negro Ensemble Company’s production of “Zooman and the Sign” at the University of Pennsylvania’s Annenberg Center Feb. 15-18.

In the play, written by Philadelphia playwright Charles Fuller, and set here in 1979, a 12-year-old girl is murdered on her street.

Even though it is almost certain that someone saw something, no one spoke to police, despite her family’s plea for help. Tension mounts in the neighborhood as the father’s anger and frustration with the community grows, while neighbors worry that his calls for justice will attract unwanted police attention and retaliation from the killer.

“I would have organized,” Stickney said. “I don’t believe that I alone can do anything. I would have had conversations — maybe not with everyone. But I would have not been alone. Sometimes people need to know you are willing to stand up. They are afraid of being the first one or the only one. Retaliation is real,” she said. However, “we’ve become too comfortable with fear. Fear has become our bedfellow.”

Stickney learned early lessons in bravery from her father, who moved the family from city to city as a director of YMCAs. In one city, he confronted people who were breaking in to use the pool.

“I saw him stand up to organized crime,” she said. “He knew who it was. I remember the night he left our house, and my mother was frightened that he would not come back alive.”

Then, too, growing up as a Black person in all-white communities, she learned how to handle standing out and being different.

“That’s the person I am,” she said. “You are talking to a woman who closed two crack houses and a heroin shooting gallery in my building,” in Harlem where she lives now.

Stickney says she’s looking forward to coming back to Philadelphia.

“There’s something magical about Philadelphia and the energy of it,” she said. “I love Philly for so many reasons. Philly is where I discovered I had something – that I had talent.”

She was a young woman living with her parents in Wilmington when she got her first break.

Because she didn’t have money for a ticket, she stowed away in the bathroom on a Manhattan-bound train.

In New York, she attended a theater workshop, wound up meeting Charles Fuller and successfully auditioned for a place in the University of the Streets Theater Co. — the official start to her career.

Her success helped her avoid a beating at home. “They had a belt with my name waiting for me,” she said. “I had broken all the rules.”

She later lived in Philadelphia, earning money as a model and a bartender at Benny the Bum’s, then at 53rd and Market streets.

In the late 70s, her home was in Powelton Village near the first MOVE compound on 33rd Street. At the time, she, a neighbor friend of hers, and many other neighbors weren’t fans of MOVE’s naturalistic lifestyle. Trash and vermin piled up on MOVE’s property.

“It wasn’t sanitary — people living in the city limits as though it was rural was questionable,” Stickney recalled.

Stickney was in Europe during the 1978 MOVE confrontation with the police that involved a bulldozer, high-pressure water hoses, tear gas and a gun battle. An officer was killed. When she returned, many neighbors had become MOVE supporters against the police.

The same dynamic plays out in “Zooman,” written a year later. Because of police actions, neighbors are afraid or unwilling to work with police, she said.

“In 1979, it was a story,” she said. “In 2024, it’s even more relevant because we have seen so many deaths at the hands of other Black people and at the hands of police. If this play can build a bridge over fear into a collective witness, then we could confront Zooman and others like him,” she said. “Collectively, we have the power, and we have to witness. We can’t turn a blind eye, especially today.”

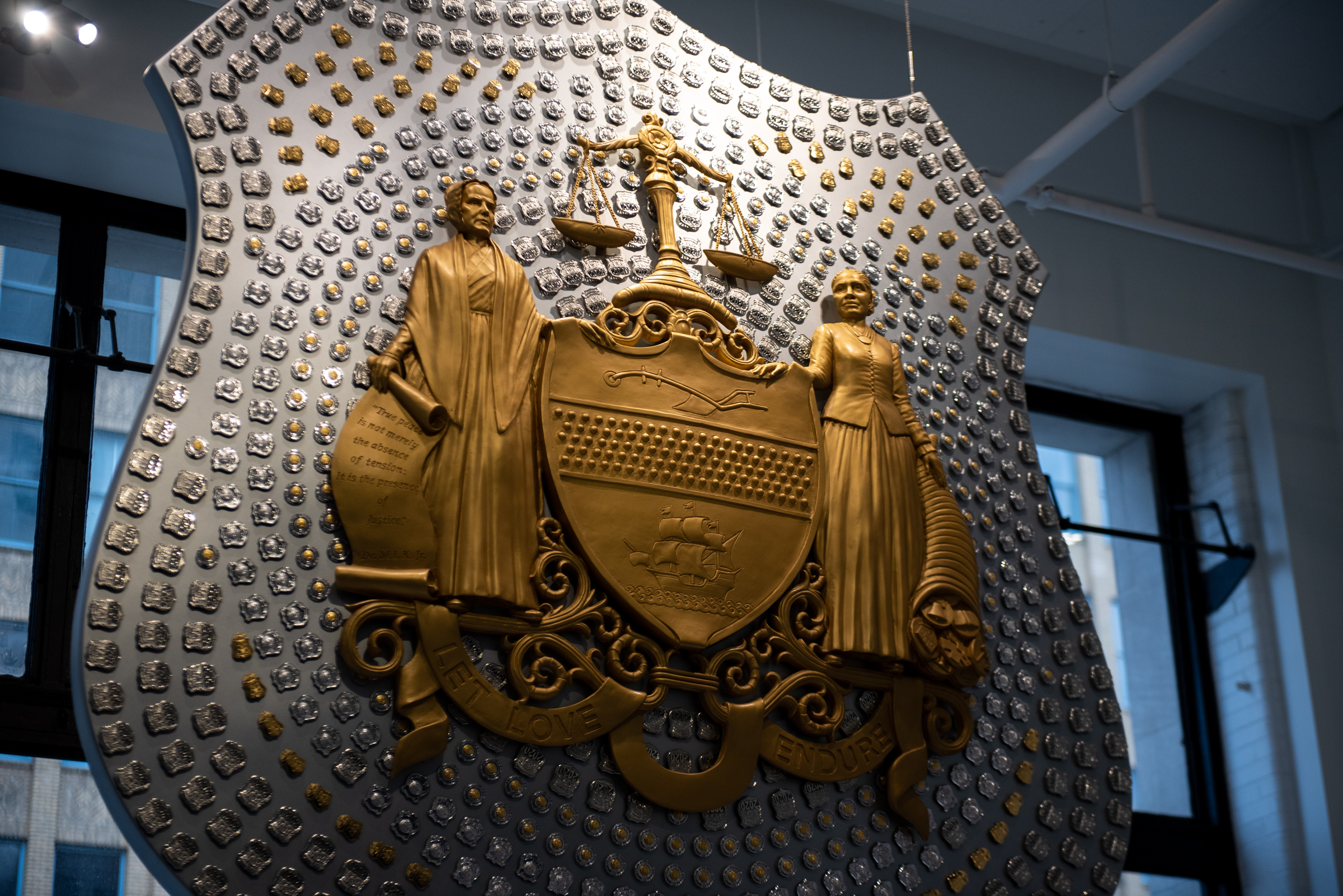

Penn’s production of “Zooman and the Sign” is being performed by the Negro Ensemble Company as part of Penn Live Arts’ artists-in-residency program. This season focuses on gun violence.

The Negro Ensemble Company, based in New York, was founded in 1967 to provide an outlet for Black theatrical talent. And what a roster of talent – Denzel Washington, Angela Bassett, Samuel Jackson, Phylicia Rashad, Billy Dee Williams, Esther Rolle, and many more, including Charles Fuller.

—

“Zooman and the Sign,” Feb. 15-18, Negro Ensemble Company, Penn Live Arts, Annenberg Center, 3680 Walnut St., Phila., University of Pennsylvania, 215-898-3900.

A facilitated story-circle audience discussion will follow the Feb. 17 matinee.