DIY Art-Punk Video Tape Transgression

The Ugly, Inspiring Shot-On-Video Horror of Charles Pinion

by Josh Lewis

One of the major drivers of the undying affection for low-budget and independent genre/exploitation cinema is its historical value as a space for artists on the margins of society to express themselves. From the grimy creature-splatter dramas of Frank Henenlotter to the psychological, confrontational sexploitation of Doris Wishman, or the transgressive humor of John Waters or Rudy Ray Moore, you can still find unexpected voices and perspectives that are frequently as funny and sad as they are seedy—not to mention from the types of people who would never be trusted with the kind of money required to make a product for a major movie studio.

Many of the foremost genre filmmakers of the Sixties, Seventies, and Eighties (even those who went on to graduate to studio filmmaking; your Wes Cravens, Joe Dantes, etc.) cut their teeth in the drive-in, grindhouse, and video store markets. It was there that a logline and a poster exploiting a genre trend that consistently attracted audiences (horror, mostly—but action, sci-fi, crime, and porn didn’t hurt) were enough to entice an investor who could see a quick financial return if the budgets were low enough; and also where you’d see early budget-conscious producer-directors like Roger Corman, Russ Meyer, and Jack Hill thrive. And for the artists that followed them, not having to secure a traditional (or large) box office haul to make that return meant little-to-no oversight on-set or in the editing bay to stifle their visions, no matter how gruesome, flawed, or contradictory they might be. As a result, it was a rare underground industry that could both be exceptionally profitable due to its limited conditions (guerilla-style location shooting, cheaper 8mm/16mm film, small casts and crews frequently made up of friends or relatives) and promoted pure formal innovation and creativity—even when the results were harsh, uncanny, and disreputable.

Any modestly curious cinephile will, at some point, find themselves watching a movie made in this production mode—either because they stumble upon David Cronenberg or Peter Jackson’s more popular, commercial period and become curious what Shivers or Bad Taste are; or because some of those no-budget 16mm visions went on to be unavoidable, era-defining masterpieces themselves, like George Romero’s Night of the Living Dead, Tobe Hooper’s Texas Chainsaw Massacre, or Sam Raimi’s The Evil Dead. With that fertile foundation in place, a 16mm J-horror industrial body-horror frenzy like Tetsuo: The Iron Man or a surreal Italian gore film like Lucio Fulci’s Zombi 2 is not too much of a leap to make—and all at once your journey towards being a sick, perverted voyeur (akin to James Woods’ trashy TV channel president Max Renn in Videodrome) is well underway.

Shot-On-Video (SOV) horror is underseen by even the most die-hard genre fiends.

But one form that frequently goes under-witnessed by even the most already-initiated genre fiends is Shot-On-Video (SOV) Horror; an underground movement that came about after the introduction of affordable consumer-grade videotape cameras in the Eighties and which tried to merge the cheap spontaneity and optical roughness of home movie camcorders with the aesthetics of extreme pornography and no-budget crime, horror, and splatter movies.

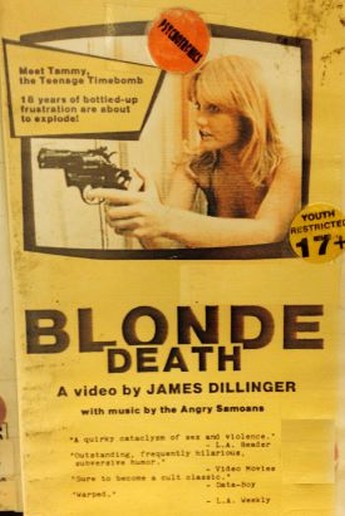

The makers of these films were even more sidelined than those who could at least afford 16mm film and be welcomed into the traditional narrative feature world of film festivals, theatrical distribution companies and VHS/DVD rental stores. Instead, they typically had to resort to pop-up screenings and selling their films like they were a printed punk zine or a mail-order workout tape. This alienation and closed-mindedness to the primitive, “unprofessional” images conjured by tape resulted in a trickle-down effect where the only people working in this mode were the weirdos with questionable, nonconforming taste who had no other choice, and thus leaned even further into that brashness in shockingly violent and comedic ways. Filmmakers like John Wintergate (whose 1982 film Boardinghouse is commonly referred to as a “cross between The Amityville Horror and a Playboy Playmates video”) and “the world’s angriest gay man” James Robert Baker (whose 1983 film Blonde Death takes a Bonnie-and-Clyde framework of romantic youth rebels on the run and channels it into a deeply misanthropic and grotesque counter-culture satire of American domestic life) were among the first out the gate, with others like David A. Prior, Alan Briggs, Mark and John Polonia, Dean Alioto, and many more to follow—all of them seemingly trying to one-up each other on the outrageous levels of gore, sex, and absurd humor they could fit on a tape.

But of all the filmmakers who came about during this movement (including that of the adjacent-sister movement out of New York called the Cinema of Transgression), the one whose work left the deepest and most indelible impression on me is Charles Pinion.

Pinion started his career as a Florida-based visual art teacher who spent much of his spare time going to local punk rock shows, cultivating a combined interest in painting and musicality that would eventually align with his taste for extreme and weird cinema and inspire his debut feature, Twisted Issues, in 1988. Twisted Issues was a project that was originally intended as a simple videotape documentary time capsule of—and love letter to—the music scene in Gainesville that he could tell no one was preserving. However, due to the collective of playful underground creatives involved (including many of his skater and goth-kid students, who Pinion even let help let write their own scenes), the production quickly transformed into a no-budget, experimental revenge-horror and splatter-comedy exploitation film about a murdered teen skateboarder named Paul who is brought back from the dead by a mad scientist with a fencing mask, a skateboard deck drilled into his foot, and a single-minded intent to gruesomely kill his punk attackers in a series of impalings, eye-gougings, face-crushings, sword-stabbings, dismembered limbs, and hangings. It’s a killing spree that takes place in a hypnotic, hazy environment of TV screens filled with broadcasts about Hitler, tacky commercials, anti-drug PSAs, and “bug people” interspersed with images of kids smoking, skateboarding, and listening to bands like Killer Fetuses From Outer Space (“… only on SLUG FM”) around graffiti-covered Florida neighborhoods, dingy apartments, and beer-soaked house parties. The film boasts the same level of run-and-gun street authenticity that made the grimy New York exploitation movies of Abel Ferrara and Larry Cohen so striking, as well as the impulsive movement and thrashing of its chosen punk scene milieu.

The whole thing is filmed like one long stream-of-consciousness musical montage/slasher sequence; bizarre Italian horror primary color lighting, abrasive avant-garde freakout cutting, a harsh punk soundtrack (including many of the local bands Pinion had originally set out to document), sudden lurching handheld camera movement, and unbearable close-ups of the gross textures of gushing, leaking wounds, eyeballs falling out, and enough sharp objects piercing bloody body parts to make Herschel Gordon Lewis proud.

At one point, a demon is seen selling LSD behind a 7/11; another scene appears to be a gruesome domestic fight over the chopping of brussels sprout; the finale involves armor, Uzis, and TV static netherworld astral projection. The result is a feverish, enigmatic work of pure love for extreme genre cinema, but also angry, humorous self-expression; a sort of “fuck you, look at this beautiful subculture that exists and probably won’t for much longer!” burst of youthful rebellion that takes full advantage of the raw industrial noise and smeary, surreal psychedelia of its video form. That the pungent, lo-fi, anarchic-DIY-guerilla SOV horror-style that Pinion located while filming it (one that, as he puts it, was more about counter-cultural energy and attitude than any sort of technical coherence) is the only reason this document was even able to be made cheaply enough to exist only lends itself further to its ugly passions and poetry—the kind that very much captures the transgressive, art-punk atmosphere of the music it was inspired by, with lyrics like “The streets are very ugly,” or “There’s a noose around my neck, it’s getting tighter all the time.”

Shortly after making Twisted Issues, Pinion moved from Florida to New York. The move allowed him to get more involved in a burgeoning arts scene, promote the film, and take a course on 16mm filmmaking, with the intent of eventually graduating to a look (and budget level) that people might take more artistically seriously. The resulting surreal, black-and-white short film (called Madball) about a failed marriage proposal that turns monstrous and nightmarish has shades of early Lynch and Shinya Tsukamoto.

You can almost hear the actors and crew laughing off-screen as they come up with one repulsive image after another.

Turning the familiar into something more grotesquely humorous and surreal is a consistent throughline in Pinion’s work, one which can be seen even in a more recent short of his from 2015 called Try Again, about a man who keeps trying to think of scenarios in which to kill himself but instead winds up trapped in a gruesome loop of all his own bodies piling up around him. But these attempts to transition into more conventionally shot short films (and a few production assistant/art department gigs, music videos, eventually hardcore pornos and dirty undergrounds comics) didn’t take. Instead, Pinion found himself graciously welcomed into the world of the “Cinema of Transgression” movement in New York, alongside artists like Nick Zedd, Kembra Pfahler, David Wojnarowicz, Casandra Stark, Tommy Turner, Lydia Lunch, and Richard Kern (who he apparently even traded tapes with before asking to be in his movie). And by the Nineties, he was conceiving of what would become his masterpiece: Red Spirit Lake.

Red Spirit Lake would take the amateur, lo-fi stylization and gory revenge movie sensibility of Twisted Issues and transition it into a dreamy, supernatural quasi-feminist pornographic snuff film. The film’s plot centered around a gruesome real estate war for the titular Red Spirit Lake, one being waged by a corrupt, powerful industrialist (and his disgusting, low-rent gangster goons—who coincidentally love torturing women) who wants to understand its “feminine secrets” and a young woman named Marilyn (played by co-writer Annabel Lee) who just inherited the house from her aunt, and who may or may not belong to an ancient coven of vengeful witches who have long suffered cycles of abuse and sexual violence at the hands of men and have turned the property into a haunted, spectral afterlife for them to play around in and subvert this history of gendered domination through seduction and violence. Even more so than Twisted Issues, Red Spirit Lake benefits from Pinion’s production philosophy, which he refers to in his wonderful interview with Mike Hunchback (available with the recent Vinegar Syndrome Blu-ray release of Red Spirit Lake) as “friends, lighting, blood”; which is to say, gathering a bunch of perverted friends together in a rural, snowy cabin; buying some camcorders, floodlights, and gels; and then gleefully pushing each other to the most violent and hilarious extremes you can imagine, until you’ve made one of the most disgusting things anyone’s ever seen on a tape and turned it into a crude painting.

Red Spirit Lake runs just over 60 minutes and features creepy male caretakers/sons of Jehovah who get abducted by aliens that they refer to as “Angels” (a counterpoint to the “demons” that possess the men to berate, abuse, and assault women when they get horny—made literal in a scene so shocking it was cut from most versions of the film, in which one of them ejaculates unsimulated into the camera); a man burned to a zombified “stinking human raisin” crisp in an outdoor sauna while screaming about the purity of his “psychic space” being ruined by women; and Marilyn becoming one with this collective, traumatized womanhood she has a biological connection to—which she does through the eventual revenge enacted on the rapists of the film. Their tongues are bitten off, their penises are mutilated and dismembered, and they are, finally, anally fisted to death by the spirits of the women they’ve hurt (including shots of the shit-and-gut-covered hand of the throat-slit woman who does it), all while laughing in glee or masturbating to this gruesome suffering. Other men get their heads crushed with sledgehammers, their chests blown open with shotguns, and finally some sort of star key” from the alien angels gets pulled out of their brain goop.

You can practically hear the actors and crew laughing off-screen as they come up with one repulsive image after another. It’s the sort of shocking display that could only be considered entertainment by people already versed in the shock-gore sensibilities of the Nekromantik films—but also one that they still take gruesomely seriously when it counts, and which they film in a series of appropriately harsh, uncanny light shows; dreamy slow-motion; distorted fisheye lenses (pushed even further with smeary warping effects) and a scratchy, shrieky industrial soundscape sometimes interrupted by jazz or spirit-summoning violins. It’s full-blown psychotic surrealism (I was not surprised to learn that Pinion was a William S. Burroughs fan) at the intersection of an experimental, underground porn video and a cathartic splatter-horror grindhouse movie. I’ve genuinely never seen anything else like it.

Not even We Await, Pinion and Lee’s follow-up film three years later, could compare, though it too has its own unique charms. Originally conceived as a larger budget, 35mm passion project about a rural family of cannibals called Killbillies, We Await rearranged a few of the basic story ideas about Americans’ sick relationship to organized religion/cults and paranoia about what could be going on in your neighbors property and wedded it to the comparable production methods of crummy apartment scuzz and floodlight color-painting of Red Spirit Lake, all shot in their own shared living space in the Mission District of San Francisco. The result is a very lo-fi, Nineties-home-movie-from-hell/California “Manson family” dynamic that has some obvious Hills Have Eyes and Texas Chainsaw Massacre shades to it, but which also has some of Andy Milligan’s hatefully depraved and perverse familial melodrama Seeds. The resemblance to this latter work is strongest in early scenes that deal with the haze of televangelist broadcasts, incestuous impulses, and the hunting and selling process of the family’s human meat business; Pinion quickly sets the stage by giving the audience a glimpse of spiked cowboy boots going into the skull and soon-to-be-eaten brains of a new capture and the depiction of another man strung up in a garage with his penis clamped with pliers and blowtorched.

At one point, the son (played by Pinion himself) is seen chopping a body up in his car and selling the flesh door-to-door like an especially grotesque drug dealer prowling the same normal San Francisco streets where people take out recycling, ride bikes, and go to school. He moves this meat alongside his Uncle Jack’s green fungus “nectar,” which transitions the film into a more spiritual form of mind-bending (or mind-control?) psychedelia that later transforms into what some of the characters refer to as a “harvest”. The film then takes the cult indoctrination and subjugation experience and drops into a disgusting, paranoid fever dream of bizarre visions, slimy sex scenes, a man who thinks he’s a dog, a very crudely surreal “spirit drive” in which the entire family loads into the car and drives around various images that range between forests, breasts, and microscopic photography that almost looks like the inside of a lava lamp, as if the family were driving through space.

At one point they run into a giant, naked, cross-bearing micro-penis Jesus played by Pinion’s porno colleague David Aaron Clark at Screw Magazine, with whom they proceed to get into a violent altercation with, as if he were a Kaiju. It’s a shocking image completely untethered from reality or taste—and even if We Await doesn’t quite cohere together in as astonishing a fashion as Twisted Issues or Red Spirit Lake, it does summarize part of Pinion’s appeal. Namely, that much like the family cult whose nectar makes you us “one mind, closer than blood,” Pinion is offering you the chance to expand your mind and become one with the beautiful, lurid weirdness—so long as you’re open to having his transmission beamed into your eyes and brain, and maybe bite into the neck of your fellow man in order to feel something.

There’s a blunt, punk-poetry to Pinion’s lurid perversity and repulsiveness, and a genuinely inspiring production mode that suggests this style of gruesome painting is open to anyone with access to friends and floodlights. To which I say: the angels are coming… and it’s harvesting time.

Josh Lewis is a freelance film critic with writing at The Film Stage and Cinema Scope, a former movie theater programmer, and host of the genre and exploitation double feature movie podcast SLEAZOIDS.

Share:

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.

This fucking ruled as an article and I am checking this shit out.