The Voyeur of Utter Destruction (As Beauty)

The Spectacle of carnage in Game of Thrones and Shin Godzilla

by Sean T. Collins

Spectacle is the language through which art communicates when the vocabulary of the everyday fails us. Fantastic fiction, an inherent trafficker in the unreal, says as much through spectacle as any art form this side of musical theater, in which excesses of emotion transcend dialogue and emerge through the eruption of song and dance. That Act Two showstopper speaks to us (or rather sings to us) because we recognize what it is to be so in love; so enraged, so bereft, so drunk on the possibilities or vicissitudes of life that mere spoken words could never capture it. Only an explosion of sound and movement will do.

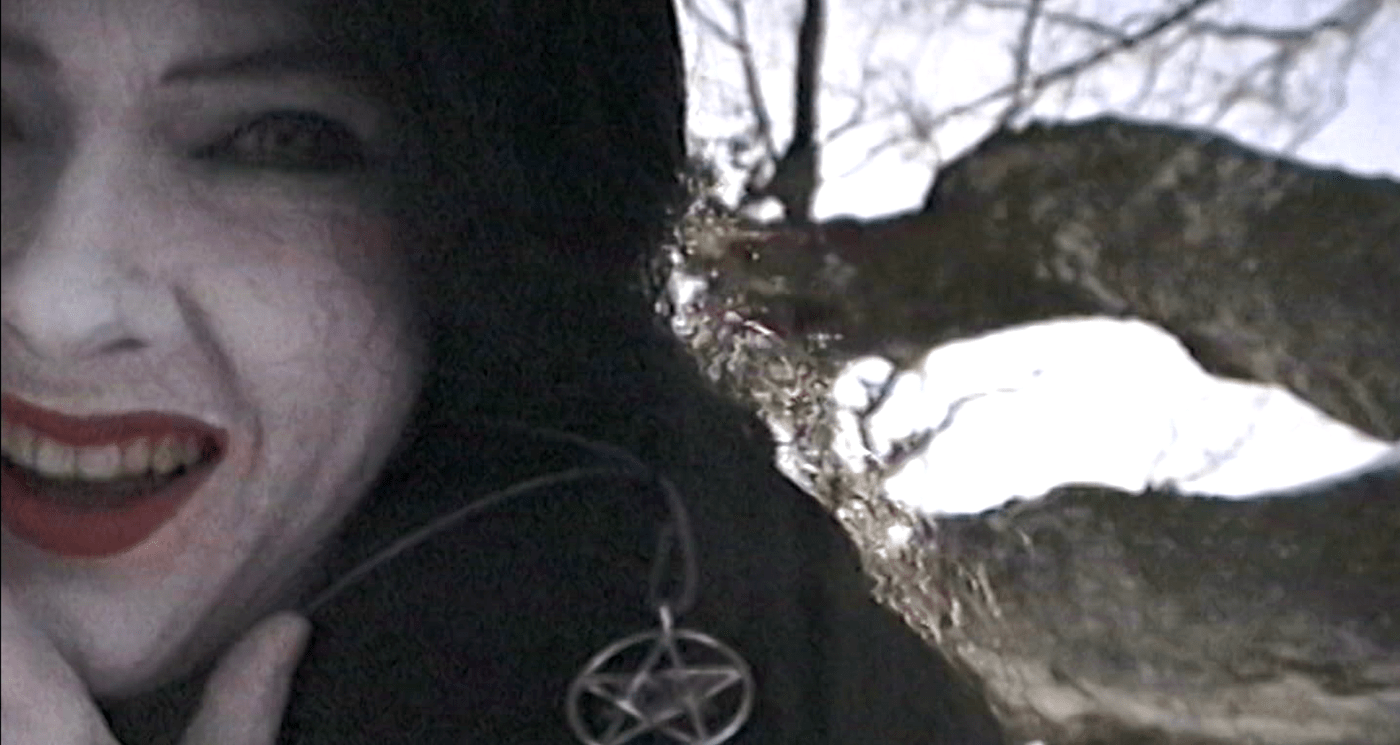

So it is with genre. The dragon, the android, and the vampire embody fears and dreams either too delicate or too overpowering for realism to express. Ratcheting up the scale and stakes of ideas and imagery like these to the level of spectacle renders them capable of handling even more intense feelings and fantasies. A trip beyond the infinite, a monumental horror-image like a wicker man aflame, a last terrible battle between good and evil: Such spectacles describe our desire and capacity as people to do things so great or terrible—or so great and terrible—that they stagger the mind.

Before they assayed updating a country’s biggest pop-cultural icon and helming the first large-scale battle on what was rapidly becoming television’s biggest show (respectively), Hideaki Anno and Neil Marshall were past masters of this technique. Anno’s Neon Genesis Evangelion pitted giant robots against increasingly bizarre godlike beings in battles that directly reflected the titanic scale of its protagonists’ adolescent angst. Marshall’s The Descent plumbed the depths of its heroine’s grief in a literal bloodbath.

Importantly, they each recognized the role of beauty in such spectacularly grim visions. From Anno’s awe-inspiring animated angels to the firelit scarlet of Marshall’s subterranean charnel pit, the gorgeousness of it complimented and enhanced the terror rather than canceling it out. Beauty is the sea salt in the caramel of horrific spectacle.

Both filmmakers applied these lessons to the biggest assignments in their careers. In 2012, “Blackwater,” his directorial debut on David Benioff & D.B. Weiss’s blockbuster fantasy series Game of Thrones, Marshall depicted the horror of war with an explosion that beggars anything seen on television before, and most of what has come since. In 2014, Anno and co-director Shinji Haguchi’s satirical but harrowing update Shin Godzilla destroyed Tokyo with an alien dispassion that reignited all the majesty and menace felt by filmgoers when the king of the kaiju first emerged decades earlier. And despite their differences, the techniques used by each to convey the magnitude of these unnatural disasters and the people they befell are strikingly similar.

Written by George R.R. Martin himself, “Blackwater” is an adaptation of the climactic battle of A Clash of Kings, the second volume in Martin’s A Song of Ice and Fire. It shows the detonation of a massive cache of wildfire—a napalm-like substance of partially supernatural origin that burns with a green flame—to destroy the invading fleet of Lord Stannis Baratheon and save the city of King’s Landing from being sacked at his command. Martin, a TV veteran, famously wrote the series in response to the budgetary and logistical constraints of the small screen, with the explicit goal of creating something so huge it could never be filmed. Fortunately, he and Marshall proved up to the challenge despite himself.

There’s something obscene about something causing so much suffering and looking so lovely in the process.

The wildfire explosion commences when an unmanned vessel full of the stuff is set ablaze at the order of the city’s unlikely guardian, Tyrion Lannister, who had earlier conceived of its use as the city’s first, last, and only line of defense against the superior Baratheon fleet. Note the word “commences” rather than “occurs”: the ensuing conflagration is so massive that it takes shot after shot simply to capture the disintegratory impact of the initial blast wave alone. The green fire is shown smashing ships into splinters, blowing sailors to smithereens, setting the very water of Blackwater Bay alight. The screams of the burning and dying mingle with the roar of the displaced and superheated air, matching the superhuman scale of the blast with intimately human pain.

Pivotally, Marshall cuts to the point of view of Tyrion and his comrades and king on the battlements, watching the explosion from afar. I still remember that first all-encompassing view of the fireball, seen from their perspective. It wasn’t simply that it dwarfed anything I’d seen from a battle scene before, it was that it dwarfed what I’d imagined seeing when I read that battle scene in Martin’s own book. It didn’t outdo the imagination, it outdid my imagination specifically.

And it wasn’t merely the size of it that hit me. It was the beauty of it, the sheer gorgeousness of that unnatural green fire. Thanks to the performances of actor Peter Dinklage, you can see that Tyrion sees this beauty too, and loathes it. There’s something obscene about something causing so much suffering and looking so lovely in the process. The contrast between the luminous blast and the agony it unleashes makes both aspects of this brutal vision work better and hit harder than they would on their own.

Four years later, Anno would demonstrate this grim wisdom in Shin Godzilla. Though this exceptional updating of the rampaging beast created by Tomoyuki Tanaka, Ishirō Honda, and Eiji Tsuburaya in 1954 is frequently lauded for its vicious lampooning of governmental bureaucracy and inaction in the face of disaster, its depiction of that disaster itself makes it a magnificent and haunting horror film as well. Anno’s script reimagines the lumbering radioactive dinosaur as a series of distinct, grotesque evolutions of a nuclear-powered self-evolving organism that has emerged from Tokyo Bay to supersede and eliminate humanity entirely.

Having failed to adequately respond to the entity’s onslaught at several previous junctures, the Japanese government discovers that it cannot be stopped or even damaged with the weapons capabilities at their disposal. The United States, Japan’s half-ally half-warden, steps in and drops MOABs onto its back from B-2 bombers high in the sky above Tokyo. These massive bombs actually penetrate the creature’s hide, unleashing huge torrents of blood—and triggering the next stage in the evolution of its destructive capabilities.

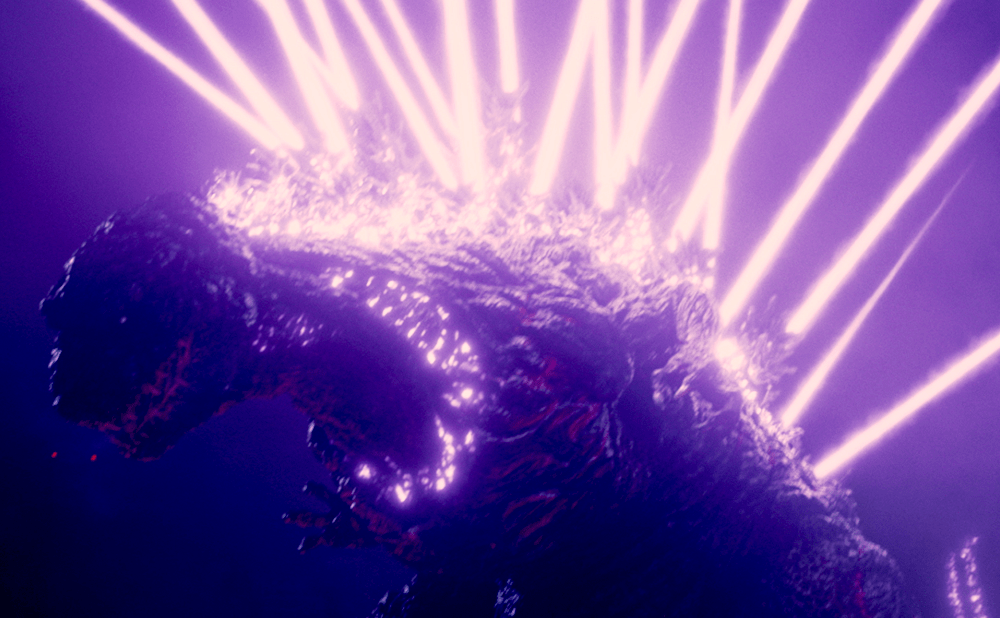

Bent low by the impact of the bombs, Godzilla’s spiny back begins to glow a bright purple. The creature opens its mouth, its jaws hinged—not between top and bottom like a normal animal’s, but in three, like something out of John Carpenter’s The Thing. Then a gout of fire emerges from its mouth like a flamethrower with an aperture the size of an office building, consuming the Tokyo cityscape in a fireball that puts even “Blackwater” to shame.

Purple beams of nuclear energy radiate out of its spines like a nightmare porcupine.

This is bad enough, but the unnatural color of Godzilla’s spinal energy signature augurs worse horrors to come. The fire narrows focus and changes hue, concentrating into a beam of radioactivity that slices through miles’ worth of buildings in an instant, like a hot knife through butter. And when future bombs are launched against the monster, it unleashes its energy in a form never before seen in the character’s long history: purple beams of nuclear energy radiate out of its spines like a nightmare porcupine, targeting and destroying planes and ordinance in seconds.

And again, the eerie beauty of this unprecedented outburst of destructive power is reflected in the faces of men in literal and figurative high places. They are—again, both literally and figuratively—powerless, as the flames and radiation are all that illuminates Tokyo’s blacked-out streets and skyline. In the film, the monster’s Japanese name, Gojira, is ascribed to a regional term meaning “God Incarnate.” The purple fire is that god’s emanation, awesome and awful to behold in equal measure.

Obviously, Godzilla is not without real-world precedent as a destroyer of worlds, and both Shin Godzilla and “Blackwater” are clearly expressions of nuclear anxiety. (In Godzilla’s case that goes without saying; indeed, the rest of the film is a race to stop Godzilla’s further evolution before the rest of the world puts an end to it, and to Tokyo, with a nuclear bomb.) The splitting of the atom on a weaponized scale is as close as humanity has ever come to harnessing such dark spectacles in reality; in a sense they are the rending of that reality itself. Not for nothing did the mushroom cloud become an iconic image in its own right; what immortal hand or eye could frame its fearful symmetry?

This essay was conceptualized just prior to the release of Christopher Nolan’s Oppenheimer, which uses the Trinity test to push the limits of the theatrical experience, just as David Lynch and Mark Frost did with television in the eighth episode of Twin Peaks: The Return. In the latter case, the atomic bomb is directly linked to the unleashing of the ultimate supernatural evil, just as Shin Godzilla and “Blackwater” tie the supernatural to nuclear reality in the opposite direction.

As well they should. In exploring our darkest fears about ourselves and our world, Marshall, Anno, and company recognize that only the intermingled beauty and horror of spectacle are capable of expressing our terror. From the striking use of secondary colors to the sheer size of it all, their spectacles show us a world beyond words—gods of hellfire, sprung from the prison of our fears at last.

*title courtesy of David Bowie

This piece was written during the 2023 WGA and SAG-AFTRA strikes. Without the labor of the writers and actors currently on strike, the work being covered here wouldn’t exist.

Sean T. Collins is a freelance writer and critic whose work has appeared in the New York Times, Vulture, Decider, Rolling Stone, Pitchfork, and many other publications. He is the author of Pain Don't Hurt: Meditations on Road House and the co-editor of the horror/erotic/gothic comics and art anthology Mirror Mirror II with his wife, the cartoonist Julia Gfrörer. He and Julia live with their children on Long Island.