Newly released Chicago Police records indicate Chicago Public Schools’ top security official denied detectives access to school video surveillance footage at a high school where a former student shot four others and that the school’s principal discouraged a witness from cooperating with homicide investigators the afternoon of the shooting.

The shooting, outside Benito Juarez Community Academy in Pilsen just before Christmas 2022, left two students dead and two wounded. Illinois Answers Project previously reported on delays in sharing information by school officials the afternoon of the shooting and over the following weeks.

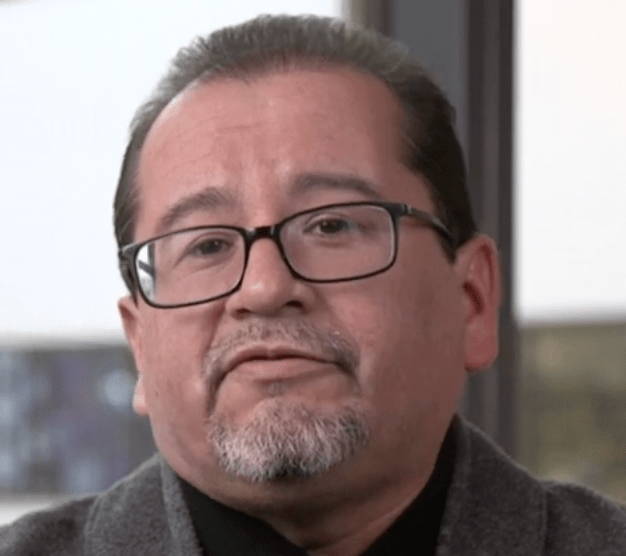

The records, obtained by Illinois Answers, show in greater detail the extent to which police say CPS Chief of Safety and Security Jadine Chou and Juarez Principal Juan Carlos Ocon did not provide critical access during the homicide investigation at Juarez High School.

Chou and Ocon “refused to allow CPD to view the exterior/interior surveillance cameras from their facility which possibly contained footage of the incident and the armed offender fleeing on foot,” according to the reports.

When police tracked down the witness school officials sent home, five days after the shooting, the witness told police they “told school staff that (they) wished to speak to police about what (they) saw but (were) discouraged by the school’s principal.”

The witness had been “sequestered” in an office by the school’s principal, according to the records, and that witness’ account of the shooting became the one that prosecutors relied on in charging the 16-year-old former Juarez student with murder.

A spokeswoman for CPS said that “CPS provided the name of the suspect and directed police to access video footage at the city’s nearby emergency center (the Office of Emergency Management and Communications) within the first hours of the police investigation.”

The records show detectives asking Ocon, Chou, and other school officials for access to school video. One investigator explained that “time is of the essence to review the video related to this incident and evidence related to this incident may have already been lost due to the delay in accessing the video surveillance system.”

He told one Juarez administrator that the video could show which way the shooter ran, location of footprints in the snow, that other evidence may be lost due to snow accumulation, that video could confirm the description of the shooter, help guide detectives in determining where to seek interviews or other surveillance footage, help locate a gun or clothing that may have been discarded, or help detectives understand if the shooter got in a car or went into a building following the attack.

The police report states another Juarez administrator told detectives, “You’ll get it when you get it.” The names of both administrators are redacted in the police report.

Chou is the district’s top safety and security official, a position she’s held since 2011, and her work includes developing and implementing district-wide school safety policy.

In an interview in May, she denied doing anything to impede the homicide investigation. She said that “it is incomprehensible that anyone would think that we, anyone else, me, anyone around me, would want to do anything to block … would block or delay or forestall progress on an investigation.”

Chou noted in the interview that detectives were eventually able to access the video.

Chou said in an interview this week that she stopped detectives from accessing the video the day of the shooting because the mother of the student witness told school officials she didn’t want to talk with police. The witness “was in the camera room,” and school officials weren’t “able to let the witness out of the camera room because dozens of police were outside the door and wouldn’t move,” Chou said.

That’s why CPS and CPD were at “a standstill,” Chou said.

Chou said the witness’s mother told school officials, in Spanish, that they wanted to leave. She said the family was visibly traumatized — the witness by what she saw and the mother for her daughter — and it “makes sense” that they wouldn’t want to talk with detectives.

“My recollection is she spoke in Spanish, was in the room literally where they were translating and asking and (the mother) said, ‘no.’ That was because they were … scared and they did not strike me as people who were like, ‘Please, we’re ready to talk to CPD.’ It makes sense they said ‘no.’ I will go to my grave with that.”

But according to records released by police, the witness’s mother told detectives that school officials told her “she should go home and take some time before speaking with police.” The witness had already provided information about the shooter to school officials and had told other school officials that they “wished to speak to police about what (they) saw.”

“(The witness) and (their) mother agreed to continue assisting with this investigation and meet with members of the Cook County state’s attorney’s ooffice,” according to the police reports.

Ocon didn’t respond to a request for comment.

Eight weeks after the shooting, a former student, expelled for behavior and attendance problems, was arrested and charged with murder and attempted murder. Last week, he pleaded guilty to murder and was sentenced to 46 years in prison. Prosecutors said he was involved in another shooting the day of his arrest, and the reports released after his conviction tie the gun from the Juarez homicide to another shooting weeks earlier.

Illinois Answers has not named the gunman since he was a minor when he committed the crime.

On the day of the shooting, the student witness told a school administrator the name of the shooter, and the administrator then gave a sheet of paper with information about the boy to the school’s principal, who would not give the information to investigators, according to police records. The records show detectives explained the situation to at least three Chicago Police Department deputy chiefs at the scene, who were unable to get Ocon or other CPS officials to share the paper.

Chou said the district’s then-deputy general counsel, Ruchi Verma, told her they could not turn over the piece of paper itself. Verma is now the district’s general counsel. So Chou wrote down the name and information that was on the paper and gave it to police.

The district’s policy, and state and federal law, all appear to allow district officials to share information during health and safety emergencies. Attorneys for CPS and CPD discussed those laws after the department’s chief of detectives, Brendan Deenihan, summarized the resistance detectives encountered for CPD’s chief attorney.

The dispute at the scene set off a months-long back-and-forth over how and when detectives are to investigate violent crime where students are victims or offenders. Records show Chou and other school officials sought urgent changes to school policy after shooting, citing “recent experiences in the field,” though nothing was formalized. Police sources said an informal arrangement now exists and detectives who investigated shootings at or near high schools at the end of January were able to quickly access school surveillance footage.

The newly released records also show how school officials responded to detectives who’d raised concerns with their supervisors and with police department lawyers about CPS’ response to the shooting. Weeks after the shooting, after a detective in the case threatened the school’s principal with a grand jury subpoena due to his lack of cooperation, Juarez school officials and district legal staff met with detectives at Juarez and admitted “procedural and strategic errors on the day of the incident,” according to the police records.

Chou, in the interview this week, said she doesn’t “remember anyone conceding anything.”

The district’s lawyers, in that meeting, told school officials to “cooperate fully with (detectives) and this homicide investigation.”

Ocon, the school’s principal, told detectives “he has been a principal for 15 years” and said he contacted CPS’ legal office for guidance because “he’s been ‘indoctrinated’ to proceed in certain ways when dealing with police and that he’s not going to change his way. (He) did not clarify what he meant.”

In the weeks after the shooting, police discussed charging Ocon with obstruction of justice but eventually decided not to proceed. CPS did not discipline Ocon nor conduct a formal review of school officials’ actions after the shooting.