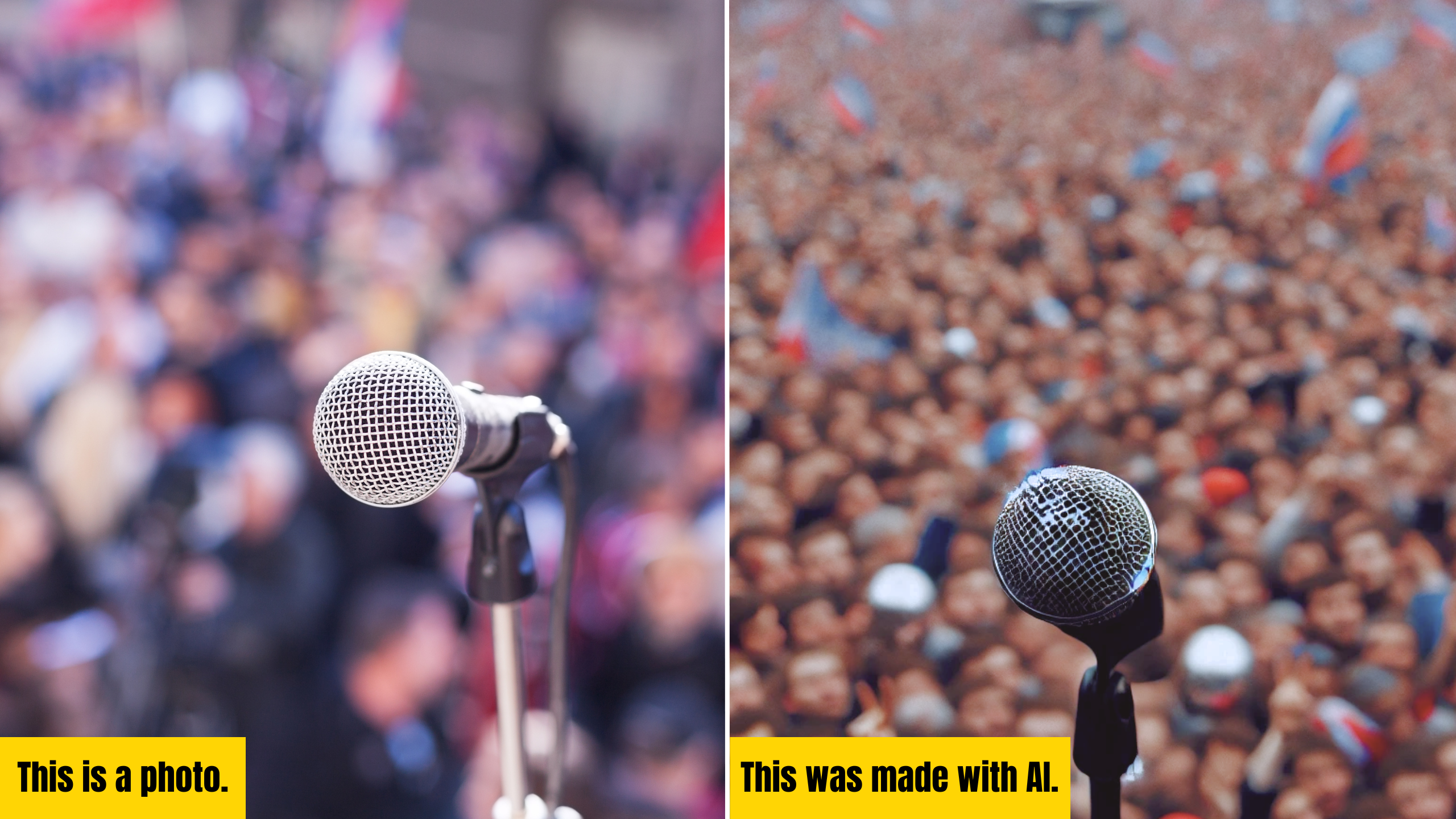

Detroiters used to being bombarded with political content leading up to presidential elections face a new challenge: That content can now be much more easily faked.

Generative artificial intelligence technologies increasingly allow regular people to create what are often known as “deep fakes”: images, audio or videos that look or sound like, say, a presidential candidate.

As these technologies get better, the content they produce gets harder to detect. AI-generated content can be easily used to spread misinformation to Detroiters, especially the one-third of residents who get their news from social media.

“It represents a serious danger that has to be monitored,” said Sheila Cockrel, former Detroit councilperson and CEO of CitizenDetroit, a nonprofit that promotes civic involvement. “The misuse of artificial intelligence could become a really critical factor in undermining American democracy while it is under assault.”

Misinformation is a threat to elections everywhere, but Detroit has a bigger target on its back as the largest city in a state known for close presidential contests. If political wrongdoers can sway enough Detroit voters with incorrect information, it could have a national impact.

Experts have varying opinions on how big of a threat AI-generated misinformation is to our elections. But they agree that staying vigilant for fake content and knowing how to detect it — when possible — is an important first step.

How can I avoid being fooled by AI-based misinformation?

Realistic AI-generated content is exceptionally easy to create but difficult to spot. Everyday people can upload information to one of many AI sites and get the computer-generated content for free.

Joe Amditis, the associate operations director of the Center for Cooperative Media who trains newsrooms how to navigate and use AI, said the best way to spot AI content is to look for things that seem a little off.

“When I’m looking at something to see if it’s AI-generated, I’m looking for little inconsistencies or logical elements that don’t make sense,” Amditis said. “I’m looking for … anything structural that doesn’t seem to have a purpose, doesn’t line up well or that doesn’t make sense within a logical, coherent, three-dimensional, actually existing world.”

There is no single telltale sign that a video or photo was created by AI, and there are no tools that are always reliable at tracking those types of posts.

The human eye may have a knack for spotting AI content. MIT Media Lab started a study in 2021 where researchers show people a series of images and ask them to determine if they were real or computer generated.

In the first iteration of the project, 82% of participants outperformed the leading AI-detection computer in detecting fake content. The project also found that the longer a person analyzed the photos, the more likely they were to guess incorrectly.

Massachusetts Institute of Technology researchers say that inconsistencies in even high-end deepfakes tend to appear in human faces. For both still and moving images, they suggest looking out for:

- Facial skin that appears too smooth or too wrinkly

- Shadows in unexpected places

- Glasses that don’t have a normal amount of glare, and the glare doesn’t change as the person moves

- Facial hair or beauty marks that look unnatural

- Eyes blinking in odd patterns

- Lips moving unnaturally during speech

Another tell is if AI-generated content evokes an “intense negative emotion,” said Rosie Jahng, an associate professor in Wayne State University’s Department of Communication.

“There is rarely going to be a case where fact-based information is going to trigger that intense of an emotion for me,” said Jahng, who studies AI and misinformation. “So if I bump into something that gets me really scared, really angry, really worried, that’s when I say, ‘OK, I need to look at other sources.’”

How can AI cause problems for elections?

AI can be manipulated into creating misleading election-related content. For example, a New Orleans street magician created an AI-generated robocall imitating President Joe Biden, which a rival Democrat later sent to voters in New Hampshire.

Michigan law would make sure an advertisement like that be labeled. Radio, television, digital and print advertisements for political candidates or ballot initiatives that appear in Michigan are now legally required to clearly disclose if they were made using AI. Federal lawmakers are exploring legislation to regulate AI technology, but nothing is concrete yet.

Social media companies, like X, Google and Meta, which owns Facebook and Instagram, have AI labeling policies for their users. But since 2020, the companies have removed policies that protect against hate and misinformation and laid off thousands of employees, including content moderators. Experts say they’re unsure if the labeling policies will be enough to catch harmful deepfakes.

Did you come across some questionable information?

Start with trusted local news outlets. Double-check them with help from these reliable resources:

- Detroit Documenters: Vote with confidence: guides to help Detroiters find the information they need to make a well-informed vote

- FactCheck.org: a nonpartisan nonprofit aiming to minimize deception and confusion in politics

- PolitiFact Michigan: a news organization that rates politicians’ statements for accuracy

- Read Across The Aisle: an app that encourages reading news from sources across the political spectrum to broaden understanding of a subject

- Junkipedia: a site that collects problematic, viral misinformation to show what threats exist and how to respond to them

No one is immune to being fooled by AI misinformation, but underserved communities may be particularly vulnerable to misinformation because their trust in political systems is so low.

These communities often disengage from the political process. They are also more likely to be fooled by AI misinformation, especially if it matches their perception of elected officials and political institutions.

Latinx communities in the United States are key targets for AI misinformation. In a recent survey commissioned by Outlier Media, Latinx voters in Detroit were especially likely to say that their vote doesn’t matter. Black people, who make up 77% of Detroit, tend to distrust American political systems due to centuries of mistreatment by public institutions. Locally, 40% of Detroit voters said they believe elected officials only care “a little” about what’s important to them.

Amditis said he worries that politicians and businesses will try to use AI to exploit information gaps and deceive these communities.

“It’s definitely not because there is some inherent weakness or inability of those communities to be able to spot or call out bulls—,” Amditis said. “(But) there’s been a historic lack of investment and infrastructure when it comes to communication in those communities in the United States.”