What does a monster look like? Ask 100 people and they’ll all tell you something different. The unfortunate truth is that the world is full of them and not all of them are fictional. More unfortunate is the history of which the monster, to a great many, has simply been the disabled human body.

The Backwards Hand is the second book by author Matt Lee. It is billed as a memoir—and it is a memoir, but it’s also much more. Lee was born with Bilateral Radioulnar Synostosis, a rare condition in which the bones in both forearms are fused, resulting in a limited range of movement. In what he aptly describes as a “collage style,” Lee explores the long-time equation of disability to monstrosity through a wide array of subjects.

Anchored by the narrative of his own experiences growing up with his condition, navigating his parents’ divorce, an early love of the arts, precarious college years, and anticipating the birth of his son. These paragraphs fluidly blend into the much larger, less straightforward narrative of disability as a centuries-long public spectacle.

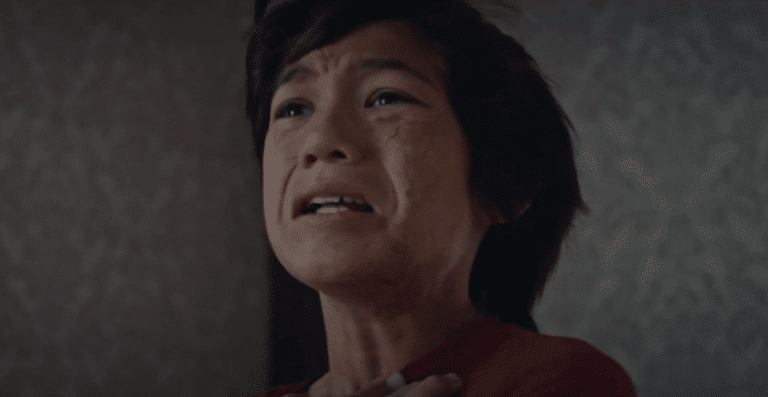

The Backwards Hand explores Tod Browning’s Freaks and depictions of disabled people in modern horror, the life of artist Frida Kahlo, “ugly laws” in the US that prohibited people with “unsightly” disabilities from being in public, the crimes of serial killer Tsutomu Miyazaki, the Nazi Aktion T-4 campaign, and more. All fluidly woven into the narrative of Lee’s own life. The result is stunningly powerful.

Author Matt Lee joined us to discuss his upcoming release, The Backwards Hand.

You use the word “cripple” a lot in this book, which is not something I expected. I’m curious about what the impetus of that choice was.

I think it’s a couple of things. First and foremost, I want the book to be confrontational. I want to deliberately use ugly and offensive language that is going to make people uncomfortable, and also kind of reflect the double standard that people still toss these words around without really thinking about how hurtful they might be.

I still hear people use the word “retard” all the time. I want to rub it in people’s faces. The second part was that in writing the book, in coming to terms with my disability, I was also trying to embrace it. So, it was kind of a reclamation of the word in the same way that “queer” has been kind of reclaimed by the LGBTQ community that can be worn as a badge of honor rather than an insult.

One of my favorite writers JG Ballard, I think he was talking about Crash, has always kind of stayed with me as words to live by: In writing Crash, I basically wanted to take humanity’s face and rub it in its own vomit and then force it to look in the mirror. So, I think my goal is to rub your face in your mess and have you take a hard look at it.

Horror films really are a major aspect of the book, and when you think about it, all this started at the beginning of cinema.

There’s a Lumière Brothers film, it’s called “The Devious Cripple”, or something. That’s probably a bad French translation. It’s about someone pretending to be crippled so they can beg for money on the street. A lot of these early silent films also played into the opposite spectrum of horror—they were comedies. A lot of these short films are about “the blind man’s dilemma,” a woman cheating on a blind man, sort of running around right under his nose, and he can’t see it.

You also start to see instances of disfigured villains very early: The Phantom of the Opera, The Hunchback of Notre Dame. Even Nosferatu is sort of taking a human form and corrupting it. Many of the pre-code horror films as well as the classic Universal movies are all about monstrous bodies, whether the Creature from the Black Lagoon or the Wolfman or Frankenstein.

It goes all the way into slasher films, too. All the key slasher franchises: A Nightmare on Elm Street, Friday the 13th, The Texas Chain Saw Massacre; the bad guy is always deformed. He’s often hiding behind a mask. It’s almost become a clich��, it’s so pervasive.

It kind of presents the disabled body as a spectacle: it’s something forbidden—it’s something you’re not supposed to see—and that makes you want to see it all the more.

That’s part of the appeal of horror films; you’re seeing something you’re not supposed to see, you’re seeing the human body in ways it’s not supposed to look; this corruption of the flesh — you see this in the film, Freaks. That’s sort of the big moral of that story: this could happen to you. You’re this close to being this monstrous freak.

On the other hand, Freaks is kind of progressive in this weird way. As you point out in The Backwards Hand, the movie shows the “freaks” as a self-sufficient community.

That’s why I especially admire Tod Browning as a director. Despite that ultimately the freaks are the villains of the film, as they enact their bloody revenge at the end, he treats them with such humanity. He really took care to humanize them and treat them with dignity.

This is something that is so rare, not just in horror but, I think, in film in general. Even though horror films co-opt the disabled body and use disfigured villains, they’re very rarely played by people who are actually disabled. It’s always make up, right? So, Freaks is a pretty rare example of not only using disabled people in prominent roles but having virtually the whole cast be made up of a wide variety of disabled people with different conditions. So that’s why I find it to be such a fascinating and important film.

It was made in the 1930s, almost a hundred years ago, and is strangely progressive. It really doesn’t go into horror territory until the final act. Prior, it shows them just going about their daily lives. They’re doing laundry, cooking food, just hanging out together, working. It doesn’t rely on sensationalizing them. It treats them in a very normal way.

To bring it into a more contemporary frame, there have been a lot of people applauding better representation today, in horror specifically, and the example I see thrown around a lot is A Quiet Place. The young woman who plays the daughter is deaf… a lot of people applauded that: “This a big leap forward for horror films. They cast a real deaf person to play this character,” but the fact that she’s deaf is a plot device.

You very rarely see a disabled person and their disability isn’t somehow called out or used in the plot. So it’s kind of mixed. Yes, it’s good that there’s more representation in a film like A Quiet Place or The Last of Us. Yes, it’s good that we’re seeing actual disabled people.

But I applaud Freaks for the representation. People argue that it’s exploitative. I kind of see it differently.

In a way, it’s an inherently exploitative genre. Regardless of the subject matter, you’re going to be exploiting something because you’re taking something that is inherently “not okay,” like murder, and you’re saying, “here, it’s fun.”

Yeah, this is where a lot of criticism of horror comes from. How can you say this is entertainment? How can you say this is art? But I think for a lot of disabled people, myself included, it becomes comforting because it’s a vessel in which we can channel otherness.

I think a lot of people respond to horror movies in this way. You see a lot of queer studies tying into horror, people from the queer community saying they love the horror genre for a similar reason. A feminist approach to horror, again for a similar reason.

When in your real life you are othered for whatever reason that may be—for whatever way you were born that goes against the status quo, and you see it celebrated on the screen, it’s a way to reflect your own experiences as being othered.

I think that’s why you have people from marginalized groups empathizing with the villains of horror films. We’re rooting for the monster. It can be fun to kind of relish in that because we don’t get that in our day-to-day existence. We aren’t celebrated for that otherness.

One of the things I look at in the book is “what does it mean to be disabled,” and I think a lot more people are probably disabled in some fashion than they might even acknowledge or realize, and if you’re not currently, you will be at some point. I promise you.

Your body is gonna break down, you will degenerate. Horror is therapeutic, it’s a coping mechanism, it’s a kind of way to work through these problems we have in terms of our identity, feeling like we don’t fit in or feeling like we’ve been ostracized or demonized. Horror flips the scripts and inverts a lot of these societal pressures that are put on us.

As long as there are people who are othered in that way, horror will continue to resonate.

The Backwards Hand is available from your favorite bookstore May 15, 2024.