Quick, name your favorite “part four” in a movie series. For every Conquest of the Planet of the Apes or Mission: Impossible – Ghost Protocol or Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home, there’s a Jaws: The Revenge or Batman and Robin or Terminator Salvation. It’s a tricky thing to pull off (maybe trickier still after the Star Wars trilogy created a template for shaping your movie series in sets of three), but studios still try it out with some regularity. Just this year, moviegoers can run out to see George Miller’s foray back to the Wasteland (with Tom Hardy filling in as Max Rockatansky in lieu of Mad Mel Gibson), followed weeks later by a fourth trip to Jurassic Park, and – at the end of the year – a return to that Galaxy Far, Far Away (the seventh Star Wars film, but the fourth to feature our old friends Luke Skywalker, Leia Organa, and Han Solo). With those high profile (and much anticipated in the old SportsAlcohol.com offices) fourth movies due out this year, what better time to make a case for a much maligned Part Four that I happen to really like. Now, since this may see me staking out a somewhat controversial position (or at least much moreso than I’d have guessed as the credits rolled on that first midnight show at the Ziegfeld), it might behoove me to establish some baseline assumptions and load you up with caveats.

Apologist Bonafides:

On a basic level, I just enjoy watching Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull. I recognize this Indy as my Indy, I think the funny stuff is funny, the exciting stuff is exciting, and it hits a lot of my personal buttons in terms of genre and period setting. I’ve certainly been accused of being a too-forgiving moviegoer, so even if I manage to get you with me in certain areas by the end of this thing, I recognize that there are going to be some aesthetic and storytelling decisions that’ll still remain divisive. Still, give me a chance, guys.

On a basic level, I just enjoy watching Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull. I recognize this Indy as my Indy, I think the funny stuff is funny, the exciting stuff is exciting, and it hits a lot of my personal buttons in terms of genre and period setting. I’ve certainly been accused of being a too-forgiving moviegoer, so even if I manage to get you with me in certain areas by the end of this thing, I recognize that there are going to be some aesthetic and storytelling decisions that’ll still remain divisive. Still, give me a chance, guys.

Indiana Jones and the Computer Generated Images:

There’s a school of thought — one exacerbated by well-intentioned “old school, practical effects” promises on the part of the filmmakers — that CGI has no place in an Indiana Jones film. On this general principle, we’ll have to agree to disagree. The original films took advantage of the state of the art in terms of film-making and visual effects (those matte shots, composites and other bits of visual trickery weren’t meant to be quaint or handcrafted, they were meant to be immersive and neat-o). There was no way an Indiana Jones movie made in 2008 wasn’t going to use computers, and while I definitely sympathize in missing the presence of real creepy-crawly bugs, I was fully willing to go with the gonzo flood of digital ants the folks at ILM conjured up in their place.

There’s a school of thought — one exacerbated by well-intentioned “old school, practical effects” promises on the part of the filmmakers — that CGI has no place in an Indiana Jones film. On this general principle, we’ll have to agree to disagree. The original films took advantage of the state of the art in terms of film-making and visual effects (those matte shots, composites and other bits of visual trickery weren’t meant to be quaint or handcrafted, they were meant to be immersive and neat-o). There was no way an Indiana Jones movie made in 2008 wasn’t going to use computers, and while I definitely sympathize in missing the presence of real creepy-crawly bugs, I was fully willing to go with the gonzo flood of digital ants the folks at ILM conjured up in their place.

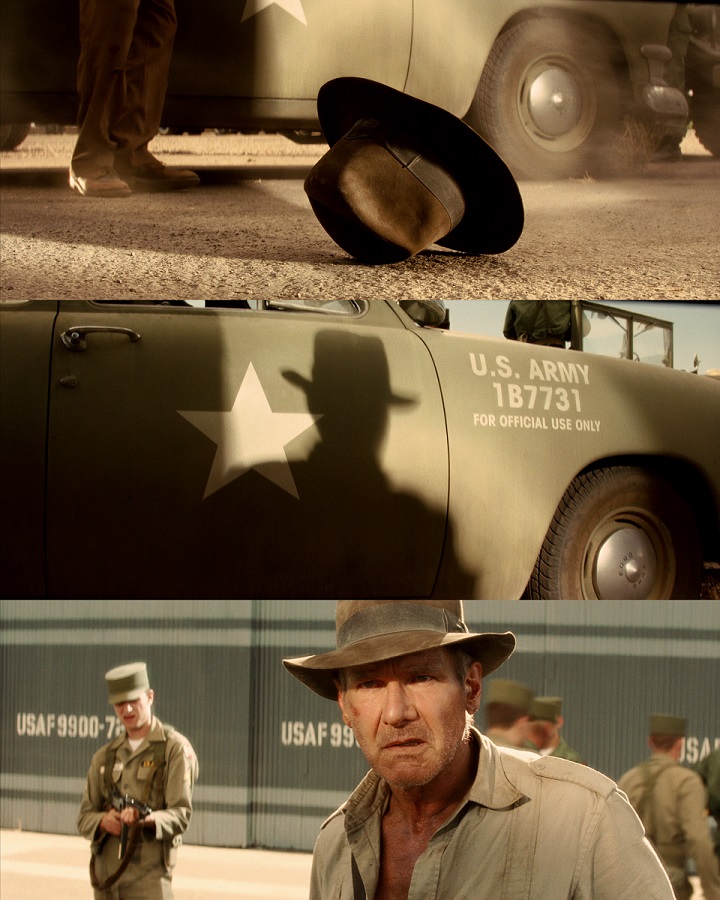

I’m also pretty sympathetic to some of the dismay at how different the film looks than the previous entries in the series. Janusz Kaminski, Spielberg’s cinematographer since 1997’s The Lost World: Jurassic Park, shot Kingdom of the Crystal Skull, making it the only Indiana Jones film (to date) to not be shot by Douglas Slocombe. Slocombe had a career that stretched from Ealing comedies in the 1950s to films like Jesus Christ Superstar and Never Say Never Again (his final credit is Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade). His work for Spielberg on the first three Indy films is iconic and rides a delicate balance between Real and Movie Real. Whatever Kaminski did in attempting to honor Slocombe’s work, while frequently arresting and often beautiful, resulted in maybe the most Movie Real film in Spielberg’s filmography since Hook. The film has something of a glowy, artificial sheen that bafflingly leaves even things that were shot for real on location looking oddly studio-bound (there is behind-the-scenes footage of the truck chase through the jungle being shot on location in Hawaii, but you mightn’t guess it while watching the film). This quality of the images also complicates the digital visual effects in the film. The CGI, usually so well-deployed and integrated in Spielberg’s films, feels of a piece with the heightened, artificial look of the film, which drags it that much further from the realism fans were expecting. But I don’t want to rag too heavily on Kaminskis’ work here, because while our opinions may differ on the aesthetic beauty of the film, it’s also still full of terrific images and classic Spielberg shot constructions (look no further than the shot that reveals Indy to us in the beginning of the film, traveling from his hat on the ground to that famous silhouette on a truck door to that familiar, if more grizzled, face).

Lucas & Spielberg:

Speaking of Spielberg, perhaps our greatest living filmmaker (I’m only including the “perhaps” to see if anybody wants to start a thread in the comments suggesting an alternative), Kingdom of the Crystal Skull seems to have joined Temple of Doom in the category of “Spielberg films that I might like more than he does.” As he seems pretty attuned to the audience (in this case I mean internet) conversation about his films — particularly so when it comes to an Indiana Jones film — he seems to be uncomfortable with it in a way that feels almost apologetic. Likewise, George Lucas seems to publicly be just fine with the Indy film they created, and he’s the subject of such weird, intense fan emotion that seemingly everything that folks don’t like about the film gets attributed to him. And some of it certainly seems to have been. Indy surviving a nuclear blast (which, yes, I thought was a hoot and a half) is something Lucas reportedly had included in multiple iterations of the project over the years, and the concept of throwing Indy into a 50s sci-fi milieu with aliens was his too (a brilliant idea; we’ll get to that). But just as the film obviously contains plenty of Lucas DNA (not itself a demerit for me, so maybe let’s agree to disagree here too?), it is unmistakably a Spielberg film. And not just in terms of the filmmaking, which bears his visual stamp throughout, but it is also stuffed with classic Spielberg thematic concerns. So while he seems to prefer in interviews to keep the focus on his attempts to please and satisfy the fans who had been asking for a fourth Indiana Jones adventure (and his perceived failure to do so), I prefer to think of it as a real-deal Steven Spielberg film.

Speaking of Spielberg, perhaps our greatest living filmmaker (I’m only including the “perhaps” to see if anybody wants to start a thread in the comments suggesting an alternative), Kingdom of the Crystal Skull seems to have joined Temple of Doom in the category of “Spielberg films that I might like more than he does.” As he seems pretty attuned to the audience (in this case I mean internet) conversation about his films — particularly so when it comes to an Indiana Jones film — he seems to be uncomfortable with it in a way that feels almost apologetic. Likewise, George Lucas seems to publicly be just fine with the Indy film they created, and he’s the subject of such weird, intense fan emotion that seemingly everything that folks don’t like about the film gets attributed to him. And some of it certainly seems to have been. Indy surviving a nuclear blast (which, yes, I thought was a hoot and a half) is something Lucas reportedly had included in multiple iterations of the project over the years, and the concept of throwing Indy into a 50s sci-fi milieu with aliens was his too (a brilliant idea; we’ll get to that). But just as the film obviously contains plenty of Lucas DNA (not itself a demerit for me, so maybe let’s agree to disagree here too?), it is unmistakably a Spielberg film. And not just in terms of the filmmaking, which bears his visual stamp throughout, but it is also stuffed with classic Spielberg thematic concerns. So while he seems to prefer in interviews to keep the focus on his attempts to please and satisfy the fans who had been asking for a fourth Indiana Jones adventure (and his perceived failure to do so), I prefer to think of it as a real-deal Steven Spielberg film.

Allen, LaBeouf & Ford:

The announcement that Karen Allen would be reprising her role of Marion Ravenwood was met with a huge amount of fan enthusiasm. The reaction after seeing the film seems to have been a combination of delight at just seeing her back on screen and muted disappointment in her performance. I tend to fall much more in the former camp. It’s still fun to see her and Ford squabble around their feelings for each other, and her smile still lights up the screen. Because the story’s construction keeps her off-screen for the first hour, we don’t get as much Marion as I’d like, but with the exception of a moment or two that indulge in some cutesiness, she’s a pleasure to watch when she is onscreen (and, really, it’s basically all worth it for me for the moment right before the truck chase when Indy tells Marion why he never settled down in the years they’ve been apart).

The announcement that Karen Allen would be reprising her role of Marion Ravenwood was met with a huge amount of fan enthusiasm. The reaction after seeing the film seems to have been a combination of delight at just seeing her back on screen and muted disappointment in her performance. I tend to fall much more in the former camp. It’s still fun to see her and Ford squabble around their feelings for each other, and her smile still lights up the screen. Because the story’s construction keeps her off-screen for the first hour, we don’t get as much Marion as I’d like, but with the exception of a moment or two that indulge in some cutesiness, she’s a pleasure to watch when she is onscreen (and, really, it’s basically all worth it for me for the moment right before the truck chase when Indy tells Marion why he never settled down in the years they’ve been apart).

On a subject that I suspect is a major “your mileage may vary” one, I like Shia LaBeouf in this movie. I think Mutt is a good character, but I also think that LaBeouf’s work in the role is perfectly judged (both for the character and as a foil for Harrison Ford) and surprisingly sensitive. I’ll get into it more below when I talk about Mutt, but I just wanted to state up front that I recognize that some folks just can’t stand him onscreen for whatever reason, even though I don’t get it in this film.

Harrison Ford has a minor version of Woody Allen Syndrome (no, not that syndrome), where there’s a strange critical amnesia around him that finds reviews (and comment sections) for each new performance expressing variations of, “it’s his most engaged work in twenty years.” Ford got these kinds of notices for Kingdom of the Crystal Skull, Cowboys & Aliens, 42, and The Age of Adaline (and he’s no doubt about to get them again for reprising Han Solo this Christmas). Each time, there’s a narrative that he’s been grumbling and sleepwalking through any film appearances for some lengthy stretch of time, and that THIS is the role that’s seen him wake up and make an effort. So it bears pointing out that Ford is really playing Indiana Jones in this movie. Yes, he growls and grumbles, but they’re Indy’s growls and grumbles, and moreover he commits to the full breadth of the role. There’s his wry bemusement with Mutt, bumbling slapstick, giddy delight at seeing Marion, and he even introduces notes of academic fuddy-duddiness that recalls Sean Connery’s work as Henry Jones Sr.

Mac’s Exit:

I’ll touch on why Mac’s demise works on a story/thematic level, but each time I’ve seen the film I’m baffled by the staging of the scene (probably the worst in any Spielberg film?). I think I see what they were going for there, as there are shots of all of the statues and treasures in the collection chamber collapsing to the ground and being swept away, presumably by the interdimensional forces being unleashed and the strange magnetism we’ve seen connected to the aliens throughout the film. But when we cut to Mac, it’s just Ray Winstone lying on his stomach. “Use your legs, Mac! I can’t do it alone!” Indy shouts, and we wonder, “Yeah, why doesn’t he just stand up?”

I’ll touch on why Mac’s demise works on a story/thematic level, but each time I’ve seen the film I’m baffled by the staging of the scene (probably the worst in any Spielberg film?). I think I see what they were going for there, as there are shots of all of the statues and treasures in the collection chamber collapsing to the ground and being swept away, presumably by the interdimensional forces being unleashed and the strange magnetism we’ve seen connected to the aliens throughout the film. But when we cut to Mac, it’s just Ray Winstone lying on his stomach. “Use your legs, Mac! I can’t do it alone!” Indy shouts, and we wonder, “Yeah, why doesn’t he just stand up?”

Now, having identified the arguments I don’t think I can win and the single worst moment in the film, let’s talk about why I think the movie itself is actually pretty great!

THE CRYSTAL SKULL:

Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade concludes with Indy, reunited with his father, riding off into the sunset. The image seemed like a pretty clear indication (at least on Spielberg’s part) that we’d seen the end of Indy’s cinematic adventures. Trilogy concluded, the adventurer had hung up his fedora. In truth, it wasn’t long before George Lucas began work on developing a story for a fourth installment. Throughout the 90s and early 00s, Lucas worked with writers Jeb Stuart, Jeffrey Boam, and Frank Darabont on a project that went by the title Indiana Jones and the Saucermen from Mars (the Stuart & Boam versions) and Indiana Jones and the City of the Gods (the Darabont version), before finally going into production with a script by David Koepp (and a story credit for Lucas and Jeff Nathanson). While a great deal changed during the development process, the core idea of juxtaposing Indiana Jones with a 1950s-style science fiction story was always there. This seems to have really rankled some fans, but it was almost inevitable that, if Harrison Ford was going to continue to play the part and Indy would age with him, it would make sense that the kind of genre story he inhabited would progress along with him. Just as the series timeline proceeded from the late 1930s to the late 1950s (replacing Nazis with Soviets as the villains of the day), Indy’s adventures would make the shift from adventure serial to 50s sci-fi, keeping pace with the B-movies of the day. And that’s why the decision to use a crystal skull as the artifact everybody’s looking for was such a brilliant one.

Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade concludes with Indy, reunited with his father, riding off into the sunset. The image seemed like a pretty clear indication (at least on Spielberg’s part) that we’d seen the end of Indy’s cinematic adventures. Trilogy concluded, the adventurer had hung up his fedora. In truth, it wasn’t long before George Lucas began work on developing a story for a fourth installment. Throughout the 90s and early 00s, Lucas worked with writers Jeb Stuart, Jeffrey Boam, and Frank Darabont on a project that went by the title Indiana Jones and the Saucermen from Mars (the Stuart & Boam versions) and Indiana Jones and the City of the Gods (the Darabont version), before finally going into production with a script by David Koepp (and a story credit for Lucas and Jeff Nathanson). While a great deal changed during the development process, the core idea of juxtaposing Indiana Jones with a 1950s-style science fiction story was always there. This seems to have really rankled some fans, but it was almost inevitable that, if Harrison Ford was going to continue to play the part and Indy would age with him, it would make sense that the kind of genre story he inhabited would progress along with him. Just as the series timeline proceeded from the late 1930s to the late 1950s (replacing Nazis with Soviets as the villains of the day), Indy’s adventures would make the shift from adventure serial to 50s sci-fi, keeping pace with the B-movies of the day. And that’s why the decision to use a crystal skull as the artifact everybody’s looking for was such a brilliant one.

Crystal skulls seem to have originated in the late 19th century as tools were invented that enabled the kind of fine carving required in their creation, an event that coincided with a rise in interest in pre-Columbian Central and South American artifacts. Skulls made their way into the trade of (fake) pre-Columbian antiquities in a cloud of hokum and invented supersitition, and many — including the famous Mitchell-Hedges skull — were bolstered by exciting stories of their discoveries, obscuring their true origins as deliberate deceptions or purchases at auction rather than legitimate, documented excavations. Still, despite their dubious origins and their eventual debunking (every skull made available for study has been determined to have been created using techniques and tools that did not exist in the pre-Columbian Americas), crystal skulls have a curiously powerful place in the mythology of the 20th century.

The most famous of the crystal skulls, the Mitchell-Hedges skull (also known as the Skull of Doom, the Skull of Knowledge, and the Skull of Love!), was reputedly discovered in 1924 by Frederick Mitchell-Hedges and his adopted daughter Anna. The elder Mitchell-Hedges was quite a character. He was an explorer, an author, and a gambler, and had spent some time obsessed with Atlantis. He offered varying accounts of how he came into possession of his crystal skull, but in his autobiography he claimed it was “at least 3,600 years old and according to legend was used by the High Priest of the Maya when performing esoteric rites. It is said that when he willed death with the help of the skull, death invariably followed.” Upon Mitchell-Hedges own death, the skull passed on to his daughter, and in the 1970s she loaned it to art restorer Frank Dorland, who would build on its legend even further. He claimed to have experienced “visionary” phenomena while in possession of the skull, saying that it emanated an aura and made him hear voices and strange noises (including bells and even the sounds of a jungle cat), and he spent a memorable day with Anton LaVey when the founder of the Church of Satan claimed that the skull belonged with his church.

The most famous of the crystal skulls, the Mitchell-Hedges skull (also known as the Skull of Doom, the Skull of Knowledge, and the Skull of Love!), was reputedly discovered in 1924 by Frederick Mitchell-Hedges and his adopted daughter Anna. The elder Mitchell-Hedges was quite a character. He was an explorer, an author, and a gambler, and had spent some time obsessed with Atlantis. He offered varying accounts of how he came into possession of his crystal skull, but in his autobiography he claimed it was “at least 3,600 years old and according to legend was used by the High Priest of the Maya when performing esoteric rites. It is said that when he willed death with the help of the skull, death invariably followed.” Upon Mitchell-Hedges own death, the skull passed on to his daughter, and in the 1970s she loaned it to art restorer Frank Dorland, who would build on its legend even further. He claimed to have experienced “visionary” phenomena while in possession of the skull, saying that it emanated an aura and made him hear voices and strange noises (including bells and even the sounds of a jungle cat), and he spent a memorable day with Anton LaVey when the founder of the Church of Satan claimed that the skull belonged with his church.

As the legends around the skull grew, it became enmeshed in the New Age fascination with pre-Columbian civilization, psychic powers, and ancient aliens. Presented as old Native American legends (they’re not), the central mythology around the crystal skulls is that there are twelve planets in the universe that are home to human (or humanoid) life, and there is a skull for each of these planets, with a thirteenth for our planet. These skulls were granted to the ancient Mayans, and when they are reunited they will reveal information about mankind’s destiny. And in perfect conspiracy theory fashion, the revelation that the skulls in question show evidence of being created by tools that post-date the Mayans by centuries only bolstered the notion that they must be the product of some ancient alien civilization. And in addition to the ancient alien connection, crystal skulls (and crystals in general, really) are regarded as items of importance among psychic circles. They are reputed to have healing powers, as well as amplifying the powers of those with psychic abilities (apparently a crystal skull will display images with whatever answers you’re seeking).

So for the purposes of propelling Indiana Jones into the era of 1950s B-movies, a crystal skull is basically a home run. Broadly, it gives Indy a way into a story dealing with saucermen that actually connects with what we already know about him: He’s an archeologist, and he’s somehow stumbled onto the trail of an actual real crystal skull! This lets us see Indy in his element in jungles and ancient temples AND still leaves him staring down a flying saucer by the end of the film, all connected naturally by real-world mythology. That shot of Indy looking up at the aliens’ craft is a mirrored bookend with the climax of the opening sequence in Nevada, with Indy looking up at that mushroom cloud. Here is the hero of our 1930s cliffhanger adventure, dwarfed by the twin symbols of the post-war atomic age.

Furthermore, the properties of the movie’s particular crystal skull have some thematic heft that connect them both to the concerns of the Indiana Jones series and the 1950s Red Scare themes that were so pervasive in genre movies of the era.

The skull, we’re told, is intensely magnetic, and we see this illustrated as various objects leap toward it as soon as it is unveiled. But really it seems to be somewhat selective in terms of the things it attracts. In fact, with the exception of some hanging lights and a pair of glasses that are attracted to the alien body in the warehouse in the beginning of the film (“a distant cousin, perhaps,” Cate Blanchette’s Irina Spalko speculates), the objects we see attracted to the skulls are telling: gunpowder, Spalko’s sword, Mutt’s switchblade, and gold coins. “Crystal’s not magnetic,” Indy points out. “Neither is gold,” Mutt counters (neither is gunpowder, for that matter). This lines up pretty well with the motivations of the main characters. Indy, Mutt, Marion, and Ox are all either trying to save each other or just return the skull and be done with it. But the skull attracts gold and weapons. Greed and power.

Indy has already passed this test years ago (we’ll get to what that means for him a little later). But Spalko wants the skull so she can learn the secrets of Akator and defeat the West. Mac wants access to Akator to fill his pockets with treasure and retire with fabulous wealth. And these are the two characters the skull ultimately destroys.

Spalko’s intentions for the skull, meanwhile, function as a perfect fantasy movie iteration of Americans’ fears of the Communist threat.

“Imagine. To peer across the world and know the enemy’s secrets. To place our thoughts into the minds of your leaders. Make your teachers teach the true version of history. Your soldiers attack on our command. We will be everywhere at once, more powerful than a whisper, filling your dreams, thinking your thoughts for you while you sleep. We will change you, Dr. Jones. All of you, from the inside. We will turn you into us. And the best part, you won’t even know it’s happening.”

Here is an explication-as-villainous-monologue of the fears that bubble under 50s movies like Invaders from Mars and Invasion of the Body Snatchers. While the Nazis in the Indiana Jones series were seeking items that would give them an advantage in martial conquest (the ark that could level mountains and render their army invincible or a grail that could grant them a permanent Reich with an immortal Führer), the crystal skull is the perfect object to symbolize the Red Scare paranoia of creeping ideology and subversion from the inside.

MUTT WILLIAMS:

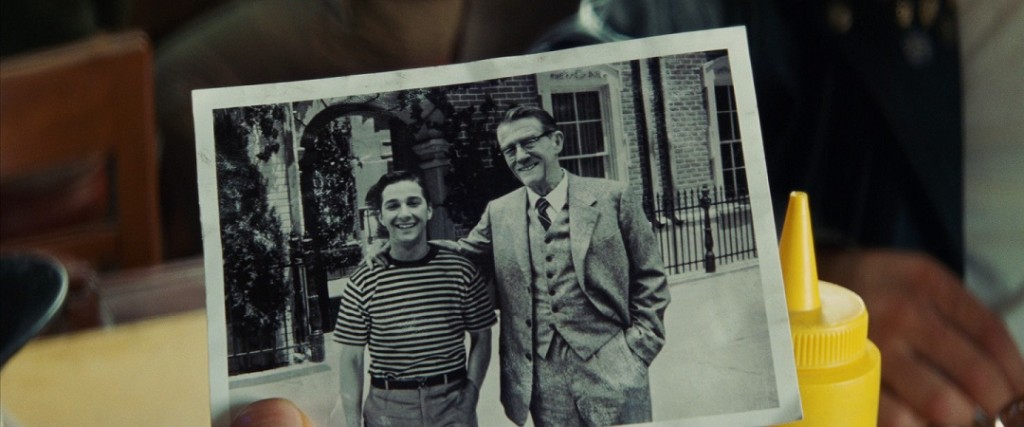

Mutt Williams (that’s Henry Jones III)’s first appearance in this film in probably the most obvious reference in any of the Indiana Jones films. It’s a bold move to introduce your new character who will spend much of the film poking at your beloved main character with a direct homage to screen legend Marlon Brando’s iconic appearance in The Wild One. I certainly remember the unflattering comparisons when the first still of that scene hit the internet, but placing it in context in the film reveals the sneaky game Spielberg and company were playing with Mutt. Whether we’re meant to think that Mutt saw The Wild One (it was released in 1953, so he certainly could have) and just copied the look or not, the connection is obvious. But instead of being meant to think Mutt (and LaBeouf) are standing in for Brando as a cool rebel, it turns out that Mutt’s appearance and attitude are obviously a pose. Spielberg makes this explicit with the charmingly dorky photo of a younger Mutt and John Hurt’s Harold Oxley in happier times.

Mutt Williams (that’s Henry Jones III)’s first appearance in this film in probably the most obvious reference in any of the Indiana Jones films. It’s a bold move to introduce your new character who will spend much of the film poking at your beloved main character with a direct homage to screen legend Marlon Brando’s iconic appearance in The Wild One. I certainly remember the unflattering comparisons when the first still of that scene hit the internet, but placing it in context in the film reveals the sneaky game Spielberg and company were playing with Mutt. Whether we’re meant to think that Mutt saw The Wild One (it was released in 1953, so he certainly could have) and just copied the look or not, the connection is obvious. But instead of being meant to think Mutt (and LaBeouf) are standing in for Brando as a cool rebel, it turns out that Mutt’s appearance and attitude are obviously a pose. Spielberg makes this explicit with the charmingly dorky photo of a younger Mutt and John Hurt’s Harold Oxley in happier times.  And of course it’s a pose! While it won’t become clear for a little while yet, Mutt is Indy’s son and Indiana Jones’s son isn’t a biker punk, he’s an adventurer.

And of course it’s a pose! While it won’t become clear for a little while yet, Mutt is Indy’s son and Indiana Jones’s son isn’t a biker punk, he’s an adventurer.

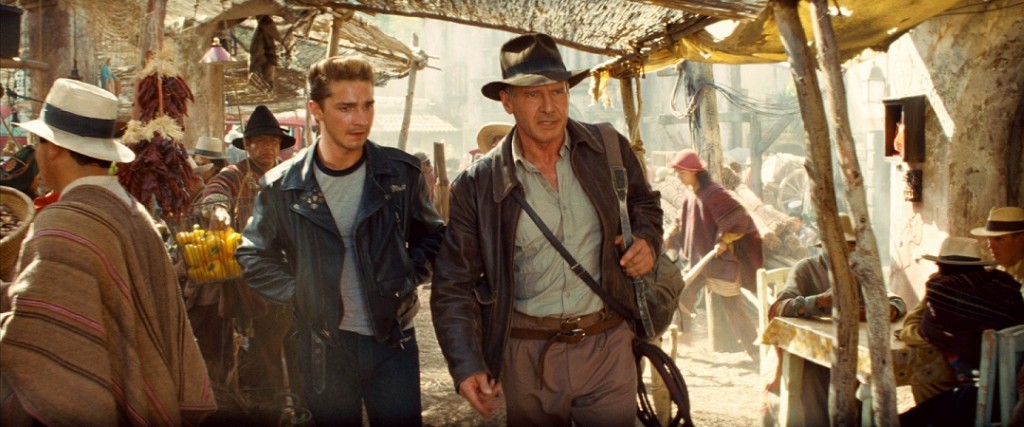

A lot of LaBeouf’s work opposite Ford sees him measuring himself against the older man. Mutt is skeptical of this old man his mother has sent him to see, and just as we can chuckle knowingly as he grumbles at Indy’s academic side, there’s real pleasure in seeing him learn just who he’s dealing with. LaBeouf uses Mutt’s flashes of anger and bravado to try and get Indy to take him seriously, all the while appraising him. Mutt is likeable because, despite his displays of disappointment and skepticism and his practiced pose of tough-guy diffidence, he listens to and learns from Indy and grows to respect and admire him for the same reasons we do. He’s also got a surprising (but sweet) emotional side, fiercely defensive of his mother and tender with the damaged Oxley.

The real meat of Mutt’s story is, of course, the development of his relationship with Indy and his eventual embrace of his heritage. As much as scenes like their conversation in Cusco are important to let them get to know each other, they also seed us with information that suggests Mutt’s poential worthiness as an heir to the Jones name. It is here that we learn that this greaser is an excellent, if restless and rebellious, student (as you’d imagine his father was). He mentions an academic background at fancy prep schools that “teach you how to debate, chess, fencing,” and he talks about being a voracious reader. Of course this is all just related to one half of the Indiana Jones persona, and for a while, as he clings to his motorcycle and his comb as totems of his adopted persona, Mutt still seems spectacularly unsuited for the more two-fisted aspects of the family business.

The real meat of Mutt’s story is, of course, the development of his relationship with Indy and his eventual embrace of his heritage. As much as scenes like their conversation in Cusco are important to let them get to know each other, they also seed us with information that suggests Mutt’s poential worthiness as an heir to the Jones name. It is here that we learn that this greaser is an excellent, if restless and rebellious, student (as you’d imagine his father was). He mentions an academic background at fancy prep schools that “teach you how to debate, chess, fencing,” and he talks about being a voracious reader. Of course this is all just related to one half of the Indiana Jones persona, and for a while, as he clings to his motorcycle and his comb as totems of his adopted persona, Mutt still seems spectacularly unsuited for the more two-fisted aspects of the family business.

Still, though Mutt has started to look up to Indy as a friend or possible father-figure for the first hour of the film, it’s the chase sequence that follows the revelation that this strange professor he’s been traipsing around with is his biological father that truly makes Mutt a great character. Just as he’s learned the truth and is trying to process the information (initially through vehement denial, of course), Indy initiates their escape from captivity and commandeers a truck. Marion too swings into action, and there’s a lovely moment when Mutt eyes his mother behind the wheel and realizes, with admiration, that both of his parents have adventure in their blood. Just as the ensuing chase through the jungle functions as a classic Indy/villain messaround, it also serves as something of a metamorphosis for Mutt. Both Mutt and the movie spend the sequence basically putting him through his paces, seeing what he can do and finding his place in the lineage of pulp adventure heroes.  He trades his switchblade for a saber, swashbuckling like John Carter or Zorro. He takes a beating with the best of them, something of a trademark of Indy himself (Ford is maybe my favorite actor to watch both throw a punch and get the tar beat out of him). And (in one of the movie’s one or two most controversial moments) Mutt even finds himself emulating Tarzan, swinging on vines through a jungle full of monkeys.

He trades his switchblade for a saber, swashbuckling like John Carter or Zorro. He takes a beating with the best of them, something of a trademark of Indy himself (Ford is maybe my favorite actor to watch both throw a punch and get the tar beat out of him). And (in one of the movie’s one or two most controversial moments) Mutt even finds himself emulating Tarzan, swinging on vines through a jungle full of monkeys.  By the end of that chase, he’s had a crash course in the family business of pulp adventure and it’s as exhilarating as it should be. He’s not just the son of Indy and Marion, he’s the heir to an entire narrative tradition, and he proves up tot he task. He even gets a slash on his cheek during the sword fight that we can imagine could become a signature scar, like the one on Indy (and Ford)’s chin.

By the end of that chase, he’s had a crash course in the family business of pulp adventure and it’s as exhilarating as it should be. He’s not just the son of Indy and Marion, he’s the heir to an entire narrative tradition, and he proves up tot he task. He even gets a slash on his cheek during the sword fight that we can imagine could become a signature scar, like the one on Indy (and Ford)’s chin.

While I obviously don’t want to see him calling himself Indiana, or wearing his dad’s fedora, I’d totally be up for seeing Mutt in another adventure (though that seems spectacularly unlikely, given LaBeouf’s comments about the reaction the film received, as well as his other very public struggles). Still, if this movie’s story about a directionless (and secretly nerdy) kid discovering he’s a full-blooded pulp adventurer and the son of Indiana freakin’ Jones is the only time we get to spend with Mutt, it was worth it.

While I obviously don’t want to see him calling himself Indiana, or wearing his dad’s fedora, I’d totally be up for seeing Mutt in another adventure (though that seems spectacularly unlikely, given LaBeouf’s comments about the reaction the film received, as well as his other very public struggles). Still, if this movie’s story about a directionless (and secretly nerdy) kid discovering he’s a full-blooded pulp adventurer and the son of Indiana freakin’ Jones is the only time we get to spend with Mutt, it was worth it.

HENRY JONES, JR.:

Here we arrive at the heart of what I think the movie does right and, while it’s not what seems to have drawn the most fan debate, it may be the most radical thing they attempted with the film. The Indiana Jones of this movie, while remaining absolutely true to his character, is finally a true Spielberg protagonist, completing a process that began at least in The Last Crusade. While he began life as something of an avatar of adventure (Lucas famously offered the character to Spielberg when the latter was denied his desire to make a James Bond picture), perfectly primed to have a series of discrete adventures in the vein of Doc Savage, inevitably Spielberg and Ford’s desire to further develop his character and tell an emotional story about the guy led him directly toward some of Spielberg’s dominant thematic concerns.

Here we arrive at the heart of what I think the movie does right and, while it’s not what seems to have drawn the most fan debate, it may be the most radical thing they attempted with the film. The Indiana Jones of this movie, while remaining absolutely true to his character, is finally a true Spielberg protagonist, completing a process that began at least in The Last Crusade. While he began life as something of an avatar of adventure (Lucas famously offered the character to Spielberg when the latter was denied his desire to make a James Bond picture), perfectly primed to have a series of discrete adventures in the vein of Doc Savage, inevitably Spielberg and Ford’s desire to further develop his character and tell an emotional story about the guy led him directly toward some of Spielberg’s dominant thematic concerns.

While he’s made movies in a huge variety of genres, with wildly varying subjects and ideas, in his more than four decades as a filmmaker Spielberg has most often returned to the tension between adventure and family. Martin Brody leaves his family on shore to go hunt down the shark that has menaced them. Roy Neary drives his family away and sets out to see the stars. Peter Pan/Banning needs to find a balance between his secret history of adventure and his responsibilities to his family. Ray Ferrier has to surrender parts of his soul to usher his children through a hellish invasion. In Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade, the audience learns about Indy’s estrangement from his father and his adventure in the film is centered around finding and rescuing his dad. Ultimately, Indy is forced to turn away from the driving passion of his life (“It belongs in a museum!”), and even the promise of immortality, in order to ride off into the sunset with his father. By the end of the film we’ve come to know much more about the man behind the fedora. We’ve seen where he came from, we’ve seen the origin of so much of his iconography (in that crackerjack opening sequence with River Phoenix as Young Indy), and we’ve even learned his real name (heck, we learn that he even has a real name!). Kingdom of the Crystal Skull continues down the path of turning Indiana Jones from a terrific adventure character into a real person (and his father’s son). He’s now referred to interchangeably as “Henry” and “Indiana,” and he’s a bit more settled, both as an adventurer and a teacher. Even the mere passage of time, read as easily in the lines on Ford’s face as in the world of greasers and “Ban the Bomb” protests he now inhabits, grounds Indy as a real man (now it’s both the years and the mileage).

This Indiana Jones not only has a history in the form of the previous three films, but he’s also lived a life in the years since we’ve seen him. We hear a bit about his exploits during the war and as a government conscriptee to make sense of the Roswell crash. And, in an intriguing move, the film even explicitly links the movie’s Indy with The Young Indiana Jones Chronicles, a television program that that followed the adventures of a young Indy, played by Cory Carrier from the age of roughly 8-10 and Sean Patrick Flannery as Indy at 16-20 (the show was later re-edited to present the stories chronologically and released as The Adventures of Young Indiana Jones, a series of feature length installments covering two of the original episodes per installment). In Kingdom of the Crystal Skull, Indy mentions being kidnapped and riding with Pancho Villa, a direct reference to the first episode, “Young Indiana Jones and the Curse of the Jackal” (now included as the second half of an episode titled “Spring Break Adventure”). The man we now know as Henry Jones Jr. has lived a lot of life by the time we catch up to him in 1957, and it’s starting to catch up to him. Old man quips about all this adventuring being “not as easy as it used to be” are played as jokes, but Indy’s age is felt in a different way as the film positions him as somebody who has outlasted his usefulness or missed the opportunity for a different, more domestic life. He’s at home when he’s scrambling from beam to beam to avoid gunfire or dodging an ancient booby-trap, but he’s delightfully, mordantly out of place when he stumbles into an idyllic suburb in the middle of the desert.

Indiana Jones has been adventuring too long to look anything but wrong in a family living room. In fact, the clash between Indy the adventurer and a (plastic & artificial) family life is portrayed as positively deadly when this picture of domesticity is immediately obliterated by an atomic bomb, the perfect symbol of the way the world had changed by the late 1950s. In the sequences that follow, we get mounting evidence that this new world no longer has a place for Indy. The younger FBI agents who debrief him are openly hostile and suspicious of him, and he is placed on an indefinite leave of absence at his university. In contemplating his next move, he takes a moment to reflect as we learn that both his father and his dear friend and mentor Marcus Brody have both died.

Indiana Jones has been adventuring too long to look anything but wrong in a family living room. In fact, the clash between Indy the adventurer and a (plastic & artificial) family life is portrayed as positively deadly when this picture of domesticity is immediately obliterated by an atomic bomb, the perfect symbol of the way the world had changed by the late 1950s. In the sequences that follow, we get mounting evidence that this new world no longer has a place for Indy. The younger FBI agents who debrief him are openly hostile and suspicious of him, and he is placed on an indefinite leave of absence at his university. In contemplating his next move, he takes a moment to reflect as we learn that both his father and his dear friend and mentor Marcus Brody have both died.

As Jim Broadbent’s Charles Stanforth, Indy’s friend and the dean of students at the university, says, “We seem to have reached the age where life stops giving us things and starts taking them away.”

As Jim Broadbent’s Charles Stanforth, Indy’s friend and the dean of students at the university, says, “We seem to have reached the age where life stops giving us things and starts taking them away.”

Then we see Indy do something we haven’t really seen from him before. He gives up. One gets the sense that he isn’t just giving up on his university and his country, he’s giving up on being Indiana Jones. He’s even left behind his adventuring fedora for this gray number.

Luckily, just as he’s about to leave town, Mutt shows up with the twin lures of an old friend to rescue and a lost city to discover, and that spark that seemed in danger of dying out inside of him comes blazing back to life. But while the lure of adventure draws him back, Indy’s goal in this film ends up being distinct from any of the previous films. He conquered his lust for fortune and glory in Temple of Doom and had his desire for knowledge and a place in history (exemplified by his “it belongs in a museum” refrain in Last Crusade) thwarted in the other two films, but in Kingdom of the Crystal Skull his stated goal is to return the artifact to its original resting place. It’s an interesting reversal for the character and it’s no coincidence that the moment the idea is planted in his head he is reunited with Marion and learns that Mutt is his son. Here again we see the notion that family can’t coexist with adventure, this time pretty blatantly illustrated as Indy learns the truth about Mutt as he and Marion sink into dry quicksand (an image made even more darkly comic when Marion and Mutt, mother and son, stand on the edge of the pit and insist that he has to embrace his greatest fear, a large snake, to keep from being pulled under). In a break from what you might expect, Indy’s feelings about family seem to be resolved not in the climax of the film but in the action sequence that follows the quicksand scene. Just as Mutt truly becomes Indy’s son during the jungle chase, so too does Indy admit his feelings for Marion and come to appreciate and respect Mutt and Marion as adventurers. When Mutt lands back in Indy’s truck after his sword-fighting/vine-swinging absence, they trade a smile and a nod that make it clear that this is a family that Indy actually wants.

Sidekick Sidebar:

Something I didn’t get into up in the “Caveats and Disclaimers” section above is that I do think the film gets a little slack in the final stretch, and I ascribe at least some of this to the pack of characters Indy is dragging around in the last third of the picture. Each successive film in the series has given him one more companion than the last:

Raiders of the Lost Ark – Indy & Marian (and for the brief stretch in the middle where he’s paired with Sallah, Marion is presumed dead)

Temple of Doom – Indy, Short Round & Willie

The Last Crusade – Indy, Henry Sr., Brody & Sallah

Kingdom of the Crystal Skull – Indy, Mutt, Marian, Oxley & Mac

Now, Spielberg is no slouch in terms of keeping each of those characters involved, but this time around it does start to feel like too much baggage.

So, with his fears of and desire for a family basically satisfied as the film rolls into its final act, Spielberg has a chance to essentially take another shot at the ending of one of his earliest features. Spielberg has said many times that if he were making Close Encounters of the Third Kind now, he wouldn’t (or couldn’t) have Roy Neary abandon his family to board that spaceship. And thanks, no doubt, to the cumulative experience of the previous three films and the first ninety minutes of this one, as soon as Indy finds himself in reach of having a family of his own, it isn’t even a question to him. That he’s essentially already turning his back on everything the skull offers is interesting because of how much of a non-decision it is for him (there’s no anguished moment where he has to pull himself away from the aliens’ offer of great knowledge or power; he already knows they need to get the hell out of there). Just as he was framed looking up at the mushroom cloud in the beginning of the film, he concludes his trip to Akator staring up at the ride he wouldn’t (or couldn’t) take as it blasts off for dimensions unknown. He’s resolved the tension between family and adventure, and offered Spielberg his do-over for Close Encounters. And only after all of that can he finally marry Marion and presumably settle down with his family (though the film is quick to point out with a wink that he is still Indiana Jones as he snatches his fedora out of Mutt’s hands on his way out of the church). There’s something moving in the idea that even a perpetual loner like Indiana Jones (a guy with friends everywhere, but who will always live alone) can get a second chance, especially later in life. It might be sentimental, or something of an old man’s movie (it’s certainly miles from the cynical punchline of Raiders of the Lost Ark), but if this is truly the last we see of Indiana Jones, I admit that I’m really glad that after all of the incredible relics and treasures he’s discovered, he also found some peace and happiness.

All right, I’ve said my piece! What are some of you favorite Part Fours? What do you think of Kingdom of the Crystal Skull? Let us know in the comments!

- The SportsAlcohol.com Podcast: The Best Movies of 2023 - February 28, 2024

- The SportsAlcohol.com Podcast: Godzilla Minus One - January 5, 2024

- The SportsAlcohol.com Podcast: Avatar 2 and the Films of James Cameron - February 1, 2023