It’s three weeks from Election Day, and early voting has begun in Georgia, a state that has been the site of some of the nation’s longest ongoing struggles over voting rights and access to democratic participation. Former state minority leader Stacey Abrams is seeking to unseat the incumbent Republican governor Brian Kemp, a rematch of one of 2018’s most contested races. Four years ago, Kemp, who was then Georgia’s secretary of state and did not recuse himself from his role overseeing the voting process, defeated Abrams in a narrow election. Abrams, who has worked for decades to get more Georgians on the voting rolls and protect those already there, challenged Kemp’s victory, claiming that it was reliant on the suppression of votes.

In the intervening years, Abrams rose to national prominence as an advocate for voter protection and for broader, deeper investments in enfranchisement. In part because of her own efforts and the work of fellow voting-rights activists, Georgia turned blue in November 2020, when the state voted for Joe Biden, and soon thereafter elected two Democratic candidates — Raphael Warnock and Jon Ossoff — to the United States Senate, elections with which Abrams was deeply involved and for which she was given ample credit.

Two years later, when she herself is again the candidate, some of the victories she worked tirelessly to make possible have come back to bite her. Georgia’s blue turn in the 2020 election provoked Donald Trump and his supporters to challenge the results there. When Kemp — a hard-right politician previously closely aligned with Trump — refused to overturn the state’s results, he got hailed nationally as a hero of partisan moderation, a characterization that has stuck. Meanwhile, Warnock is running to keep his Senate seat against former football player Herschel Walker, and much of the state’s, and the nation’s, attention is on that race.

As Abrams trails Kemp in the polls, there are some grim ironies in play. The attention and acclaim she got for her work to elect others — men like Warnock, Ossoff, and Biden — have not been equaled when it comes to her own pursuit of political power, a microcosm of the role Black women are repeatedly asked to play within the Democratic Party, which counts on them as the hardworking base that turns out votes and wins elections for other people, but who too rarely are offered robust support for their own candidacies or leadership. The United States has still never managed to elect a single Black woman governor in its history.

Abrams has long argued for building political power at a state level, and in the wake of the Dobbs decision this summer, it seemed possible that the Democratic party and the media that covers politics would come to see things her way. With Roe overturned, state and local officials — from prosecutors to governors to legislatures — will determine what kind of access entire regions will have to reproductive health care. Dobbs might finally have galvanized Democrats to consider investing in state races in the way that the GOP has over decades. But after the Kansas referendum in August, in which voters decided by an overwhelming margin to keep abortion legal in the state, renewed hope that Democrats might keep the Senate blotted out the focus on state races, leaving candidates like Abrams dangling while the media turned its attention to individual Senate contests.

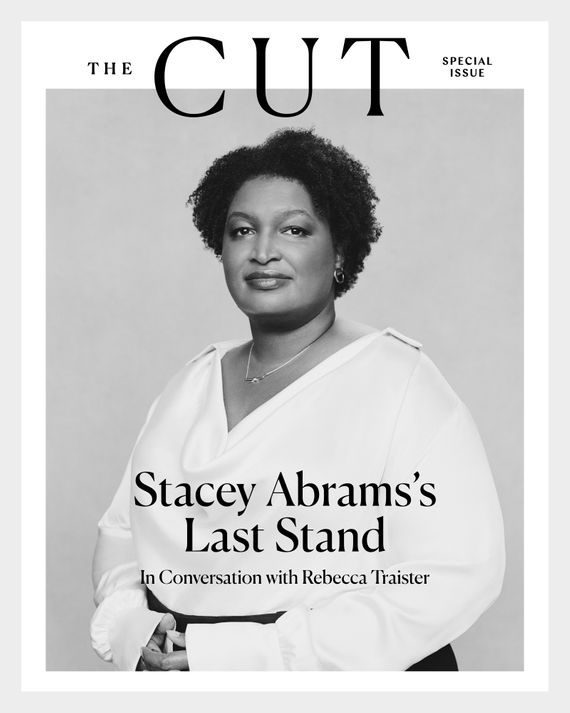

I recently sat down to talk to Abrams about all of these dynamics.

I want to start by asking you what it’s like down there right now. What is the energy, and what is different from when you ran this race four years ago against the same opponent?

What I’m finding is no matter where I go, there are people who I wouldn’t expect to already be excited about the election, who are showing up and who are voluble about their engagement. I was at Arab Fest, and the number of people who came up to me there was exciting, but what was even more telling for me was the number of men bringing up their daughters to say hi, to make sure I took a picture with their girls. I was at one massive music festival that happens over several days, and I’m interrupting music, which can always be dicey, but the response from the crowd was extraordinary. We are in the normative phase of midterm campaigns, when people are starting to dial in, to pay attention, and the response is incredibly heartening.

But. It is not the same as four years ago. Four years ago, I was running for 18 months. I had a competitive primary. I had a competitive general. Trump was the president of the United States. My opponent was talking about rounding people up in his truck. He was pointing guns at people on television. And so the contrast was starker. The excitement was different because it was a sustained level of intentional investment for 18 months, and I was brand-new. People know me now, and that’s going to change the dynamism in how I enter the space. What I’ve been so heartened by is that it hasn’t dampened the enthusiasm for what I represent.

But the other through line is that people are afraid. They are worried about money, they are worried about their children, about public safety; they’re worried about gun violence, which is on the rise here in Georgia. Women are worried about their personal safety in the state of Georgia because of the abortion ban. They are terrified, and they know that they can be subject to investigation. There are women who are being denied access to prescriptions. People are anxious, but they’re also desperate for hope.

You are credited with having done so much of the work to turn Georgia blue in 2020. Two years later you are again a candidate. Do you feel like the rise in your fame is an impediment or has helped you as you run this race this time?

Yes.

Say more.

So let’s be honest. I’m not different in terms of policy prescriptions, intentionality, or methodology than I was four years ago. Someone I was recently talking to said the comity that I bring to spaces was my trademark, and it remains how I operate. But I’ve also been successful in lifting the fortunes of my political party. So for those for whom I was a safe Democrat because I could help get things done but didn’t have too much power, I am now a pariah because it’s one thing to be bipartisan when you were in the weak position, but quite another to be bipartisan when you have the power to actually set the agenda. I’ve also been caricatured by Republicans in ways that are completely detached from reality; I’ve become an avatar for all of their invective and all of their disappointment about 2020 and 2021. And for some, I am also representative of a changing demography that is concerning.

On the other side, it is incredibly helpful, because people who did not believe more was possible now see me also as an avatar for all of the things that can be done, for the organizing that can happen; they’ve seen in real time what I can do. I’ve been able to pay off medical debts. I’ve been able to help people get Wi-Fi devices. They believe I can get something done because I’ve demonstrated a capacity for delivery both at the state level and on the national level. And so for those whom I am the embodiment of what is possible that they like, I’m great. But for those for whom I’m the embodiment of what is possible for things they despise or afraid of, I am a horrific manifestation of their nightmares.

So I don’t have the comfort of anonymity or the luxury of being able to shape my own narrative in the way I did in 2018. And that’s just the cost of trying to do good, of fighting for the things I believe. And it would be folly to bemoan how the other side sees me because it would require that I undo the fight for democracy, that I undo the fight for women’s rights, that I undo the fight to lift up marginalized and disadvantaged communities. So my job is to just overcome. Those who despise, I have to overwhelm with those who admire and who want.

Now for the reputational trajectory of your opponent. There was a view of Brian Kemp four years ago as the hard right. But there has been a recasting of Kemp as reasonable because of his decision not to go along with Trump’s desire to overturn the results in Georgia, and it has had a transformative effect on his reputation. I’m curious to hear you describe that effect and what you think about it.

It is a lie. He did not commit treason, which is exactly what every other governor in American history has also managed not to do. Yet the fact that he did not commit treason often obfuscates the fact that in response to the election, he put in place even harsher voting laws to ensure that if he were reelected, or no matter who gets elected, they wouldn’t have to commit treason to achieve the outcomes that Donald Trump sought. The election-denial frame is myopically focused on outcome, which is what Donald Trump has argued. But where Brian Kemp is a master is election denial through access. Voter suppression is about denying who can actually participate. And he is unparalleled in his commitment to that. He has said out loud: I was frustrated by the outcome of 2020 and 2021, so I changed the laws.

And because we have become, as a nation, so focused on this one man’s failed crusade, and that’s Trump, we have ignored all of his acolytes. Brian Kemp is still a fan of Donald Trump. He refused to say a bad word about him. He has embraced his entire agenda. Every hard-right conservative policy that Donald Trump trumpeted, Brian Kemp has implemented and has actually exceeded him. And so it is a terrifying reality that the national media is lionizing someone for doing exactly what they have vilified Donald Trump for doing. I mean, it is a sleight of hand that is worthy of acknowledgment, if not praise. I acknowledge that he has managed to convince America that he is the exact opposite of what his policies demonstrate. He is Ron DeSantis, he is Greg Abbott; he’s just quieter about it.

Can you describe in more detail how he has made laws that make it harder to vote?

Voter suppression is, Can you register and can you stay on the rolls? Can you cast a ballot and does your ballot get counted? Fair Fight and other organizations have made it harder for him to purge voters from the rolls directly. Through our lawsuit, we were able to get 22,000 people back on the rolls. But what they’ve done instead is outsource it. There is now a provision in state law that allows for unlimited challenges to a person’s voter registration. Here’s what that means in practice. White supremacist groups have already come into Georgia, and in the 2021 election, they lodged 364,000 challenges. This time they’ve done 64,000 challenges. What happens is they file these challenges against a voter, and in many cases voters get this ominous letter saying, Your registration has been challenged. You must appear at this hearing to prove you have the right to vote. For low-propensity voters, people who don’t have lawyers or aren’t lawyers themselves, this can be a gut-wrenching letter that makes you think, Oh my God, I don’t know what this is, but I’m not getting involved. So you’ve stopped people from voting. Just this week we had more than 1,000 people challenged in one county; they were disproportionately Black, disproportionately students. It was intentionally designed to knock them off the rolls in one of the counties that flipped in the last few elections.

So that’s No. 1. No. 2 is, can you cast your ballot? In 2020 and 2021, Democrats for the first time won the votes in the absentee-ballot race. So Kemp has made it harder by requiring that you have to use some form of ID when you apply for an absentee ballot. We’ve seen rejection rates go up, and we’ve seen participation rates go down. Because of his behavior, senior citizens, especially Black and brown senior citizens, are having a more difficult time. The disabled are in deep trouble. These are many communities that don’t have the kind of state ID they need or don’t have access to a photocopy machine. There are impediments built into poverty and age and ability that he took advantage of.

The third is provisional ballots. Provisional ballots are incredibly important, because this is a massive state where the polling places change, and you stand in line for four hours, get to the front of the line, and find out you should have gone to a place that’s two miles down the road, only the bus doesn’t arrive for another hour. You used to be able to file a provisional ballot because you were in the right county, you had the right idea. Well, you can’t do that anymore unless you show up between 5 and 7 p.m. on Election Day. Any other time, any other mistake, whether it was yours or the county’s, you’re out of luck. You don’t get to vote.

Why those hours? What’s the thinking …

It curtails and constrains access to the right to vote. There is no logic, there is no data, there is no proof point other than they know that in 2020, Joe Biden won Georgia by a margin of 12,000 votes; half of those were on provisional ballots. When you eliminate those provisional ballots, his margin goes from 12,000 to 6,000 votes.

The last one, the one that’s just mean-spirited and angry, is that in a state where voting can take up to 11 hours, they made it illegal to get water or food. So you’re standing in line for three and a half hours, you brought an extra bottle for your kid, she’s crying, she’s thirsty, and she drops the bottle, the water spills. No one can give you new water. You have to hope that there’s a random polling person who doesn’t have to be inside helping folks, who is manning a water station so that you can go and get water. Because outside groups, even nonpartisan groups that have nothing to gain except offering comfort and aid, are not permitted to give you water or food. And that’s the new Brian Kemp.

I want to ask about the focus on state versus federal elections. You have one of each in Georgia right now: your gubernatorial race and the contest between Warnock and Walker for the Senate. This summer, I watched Democrats, in the wake of Dobbs and expecting to get creamed in the fall, begin to think about the 50-year failure to prioritize and strategize around building state power — from school boards to state legislatures. Then, after the Kansas referendum, it felt like a lot of powerful people in or adjacent to the Democratic Party decided that they could in fact win the Senate, on abortion, despite decades of shying away from strong fights for abortion access. So, suddenly, energy and attention that might have gone to state races like yours was sucked back into federal battles, which is ironic because state races might arguably have a bigger impact on issues including abortion than federal ones. Can you lay out the differences between you and Brian Kemp on abortion and contraception and how who sits in the governor’s seat is going to matter for your state and the region?

Let’s start with what has been happening for about 20 years at the Supreme Court level. There’s been this very intentional trajectory of taking settled federal protections of civil liberties and deciding that those civil liberties are only protected based on the state that you’re in. Dobbs is the most recent example, but for me, Shelby was a big part of it. Shelby was the Voting Rights Act protection that was eviscerated by the Roberts Court in 2013, which permitted someone like Brian Kemp to shut down polling places. He was no longer held accountable to a federal law that said that the state could make decisions about the quality of your citizenship based on your geography. I want that to sink in: For Americans, the quality of your citizenship is entirely reliant on which state you happen to live in, which means that it’s not truly about your citizenship anymore.

When it comes to reproductive rights, what the Dobbs decision said is that whether you get reproductive, medical care is left to the governor and the legislature. And in 2019, Brian Kemp passed what was, at the time, the most draconian abortion ban in the South: a six-week abortion ban that says that you cannot get reproductive care after six weeks, which is before most people know they’re pregnant, unless you are the victim of incest or rape — and in that case, you must get a police report. And we know that roughly only about 30 percent of women actually report rapes because it is traumatizing. So, essentially, there are no abortion rights in Georgia after six weeks. Then you layer on the long-term implications of what’s happening at the Court. Brian Kemp does not believe in abortion except, he says, when the woman’s life is at risk; he does not agree with the exceptions in the law right now for rape or incest — he wants them to be gone. He agrees with Greg Abbott that there should be a bounty system in the state of Georgia. He has been silent on whether there should be surveillance of women’s social media and phones to track whether or not they have had an abortion. Under his law, you can be investigated for a miscarriage. And we are a state that has limited access to medical care anyway. We have 82 counties without an OB/GYN, 64 counties that do not have a general surgeon, 18 without a family doctor, nine that do not have a doctor at all; one in five women in Georgia does not have health insurance. Brian Kemp refuses to expand Medicaid. Georgia has the highest maternal mortality rate in the nation, and Black women are three times more likely to die than white women. That’s Georgia under Brian Kemp.

Georgia under Stacey Abrams is very different. These laws only passed by one vote in the House and three votes in the Senate. I will get those bills repealed. No. 2, I will expand Medicaid to provide access to health care, but that will also increase the number of doctors, the number of OB/GYNs, the number of women who actually have access to consistent health care. Thus, if they choose to get pregnant and choose to carry a child to term, they can actually survive.

To be clear, when it comes to reproductive-health-care access, it also matters where you are regionally. So making abortion more accessible in Georgia wouldn’t just have an impact on Georgia but on the whole South.

I am in the only competitive gubernatorial race in the Deep South, and let’s widen it out. I’m hopeful for my friend Beto. I’m hopeful for my friend Charlie Crist. But from Texas and Oklahoma across to South Carolina, from Tennessee down to Florida, if Republicans hold on to power in all of these states, there will be no access to abortion for a massive swath of the country. To put a finer point on it, 56 percent of Black people — more than half of Black Americans — live in the confines of the states I just listed, and they cannot get access to abortion care unless they have the financial wherewithal to drive across Mississippi, Alabama, Louisiana, and Texas to get to Nevada. Unless you can find somebody who can take you through South Carolina to somebody you know in North Carolina — unless you can go far north. Essentially, I would be the only governor who would repeal those laws and create an oasis for opportunity for health care. That’s what’s at stake.

And Brian Kemp does not care. He believes in religious-freedom language that says that pharmacists can deny you your prescriptions based on their ideology. In Georgia, we’ve got dozens of counties where you don’t have a CVS and a Walgreens; you’ve got one guy who controls all the prescriptions. They are denying prescriptions right now in Georgia for ulcers, for arthritis, for lupus because those medications might be used as abortifacients.

Because we’re talking about the power of state government, a lot of people reading this probably don’t know about the Supreme Court case that is to come this year, Moore v. Harper. Can you describe what that case is about and why it makes the question “Who has power within a state legislature?” more crucial?

The Moore case basically creates what’s called independent state legislature, meaning that federal election laws would no longer be subjected to review by state court or federal court. The Moore decision could say that state courts can’t review election laws, but there’s also the Merrill case, which is before the Supreme Court, that knocks out the final leg of the Voting Rights Act. We lost part of it with Shelby, part of it with Brnovich; this one gets rid of the last leg. In the South, you won’t have the Voting Rights Act, and you’ll have a governor who has unilateral authority to put in place any legislation on election laws that the state legislature will give him. If it’s a Republican state legislature, which it will be, and it’s Brian Kemp, that means that the state of Georgia can go from a winner-take-all Electoral College system to a congressional-district system.

These guys are really smart; they’ve been building this — like a pyramid scheme, but not the one that takes your money. This is like Egypt. This is pyramids: solid, lasting edifices to the erosion of democracy and participation. They’ve built it up so that when you get to the pinnacle, under this Supreme Court, Brian Kemp can make certain he doesn’t have to commit treason this time. He just has to say that even though Joe Biden wins 16 Electoral College votes in the state of Georgia, they’re going to allocate them based on congressional districts. So instead of getting 16 votes, he gets five. The remaining votes get allocated based on the congressional districts that got gerrymandered, and he might get the extra two depending on how they write the law. Because they give the governor the authority to deploy the last two votes.

That’s what’s at stake. Then you add in the upcoming SCOTUS case 303 Creative. That’s a law that’s going to say that if you are a member of the LGBTQ+ community, sexual orientation does not guarantee you public accommodations. This has been settled federal law for decades: that you can go into a hotel and they can’t deny you a room; you can go into a restaurant, they can’t deny you a seat; you can go into a shop, they can’t deny you service. If they decide, which they will, that public accommodations does not include sexual orientation, in 45 states, nothing changes. Georgia is one of five states where we do not recognize public accommodations in our law at all. We are only protected by federal law, and this will be eliminated. And because we know 303 Creative is a precursor to the end of Obergefell in the state of Georgia, the LGBTQ community will not only lose the right to accommodations, the right to basically live your life; you will also lose the protection of marriage equality because Georgia has an anti-gay-marriage law. If we thought Dobbs was devastating, we ain’t seen nothing yet.

For Georgia, though, that means we lose the entertainment industry. If women can’t get reproductive care and the LGBTQ+ community can’t get any access, why would the entertainment industry stay here? Why would the tech industry stay here? Why would businesses come here when the people who work for them do not have the ability to live in the state? And if we think, Oh, he won’t do that, this is the same man who stripped Delta Air Lines of a tax credit because it got mad at him for a gun law. And look at what we just saw Ron DeSantis do to Disney. That’s the kind of leadership that Brian Kemp is promising Georgia.

Right now, you are trailing in the polls. So what are you looking at for the next three weeks?

We are a polarized state, and polling is a snapshot. The question is, Who are they taking pictures of? A lot of the recent polls apparently are taking a picture of Indiana; they are not looking at the demography of Georgia. But Georgia is a turnout state. What I have been lauded for, what we have done in Georgia, has been to turn out voters that are often discounted. So the next three weeks are about reminding people of why Brian Kemp should be fired, explaining to them why I should be hired, and reminding them that they actually have the right to more.

I need people to trust that they deserve more. Too many of us have been lulled into believing that we’ve gotten all we’re going to get. But we’ve got a $6.6 billion surplus that can be invested in every single facet of our lives and make our lives better. And it will not require increases in revenue. We just have to spend the money we’ve got on the people we have for the things they need. And if we do that work, we win.

To your earlier point, the attention is always focused on the sexy federal level, but our lives are lived at the local level, and governors are the most powerful forces that few people understand. I will not only be the best governor for Georgia, I will be the first Black woman in American history to be governor. And you don’t elect someone for history, but, by God, why miss an opportunity to make history?