When women received the right to vote in the United States 100 years ago, it marked the start, not the conclusion, of the fight for gender equality. While the Equal Rights Amendment typically conjures up images of protesters in bell-bottoms and wedges, the truth is, it was first introduced in 1923 and only gained momentum in the 1970s. By the time Mrs. America, FX on Hulu’s new nine-part limited series about the efforts to pass the ERA, begins in late 1971, the amendment is on a fast track to ratification, with clear-cut bipartisan support. The House of Representatives passed it in October 1971, and the Senate followed suit in March 1972.

But as Mrs. America tells it, once the ERA was introduced to the state legislatures, the three-quarters majority necessary for ratification went from a sure thing to an uphill battle for the second-wave feminists like Gloria Steinem leading the charge: Phyllis Schlafly, a staunch conservative, mobilized a grassroots movement against the ERA that ultimately played a large role in its defeat. The amendment failed to pass in the required 38 states by its 1982 deadline.

Although Mrs. America opens every episode with a disclaimer that “some scenes and dialogue are invented for creative and story-line purposes,” this is a well-documented time period that doesn’t need to digress very far from the truth for the sake of a captivating story. That being said, we’re diving into the historical background of the series’ central figures to help determine when and how Mrs. America blurs the line between fact and fiction.

(Note: Due to Mrs. America’s depiction of historical events, this article includes spoilers.)

Phyllis Schlafly (Played by Cate Blanchett)

The “villain” of Mrs. America, Cate Blanchett’s Phyllis Schlafly epitomizes the worst kind of female ambition. Hidden behind a charming demeanor and a gleaming smile is a power-hungry Republican Party darling with a dangerous talent for massaging the facts for political gain. This predisposition for spinning the truth is best described in a 2005 New Yorker article in which Elizabeth Kolbert pronounces Schlafly’s 1964 book A Choice Not an Echo as mixing “fact, sensational accusations, commonsensical truths, and elaborate conspiracy theories into a compelling but evidently bogus narrative.”

Blanchett, an executive producer on Mrs. America, gets Schlafly’s patrician cadence down pat, but, more impressively, also manages to extract a shred of sympathy for her anti-feminist character. The series’ thesis is that Schlafly, who died in 2016, became the ERA’s most famous opponent because it was the only way she could succeed as a conservative leader in a sexist world.

The official story of Schlafly’s involvement in the anti-ERA crusade is that she was asked by a friend to speak about the issue in late 1971. After reading up on the subject, Schlafly decided the amendment was a “fraud” and used her political skills — she ran for Congress in 1952 and 1970, losing both times — to keep it from being ratified in the States. Mrs. America, however, presents a much more dramatic pivot: The series stages a Washington, D.C., meeting between Schlafly and several male Republican lawmakers, including Senator Barry Goldwater, for whom Schlafly aggressively campaigned for president in 1964. The meeting is ostensibly to discuss the Strategic Arms Limitation Talks, a.k.a. SALT (Schlafly positioned herself as a national-defense expert during this time), but the conversation soon turns to the ERA — though not before Schlafly is asked to take notes in her own meeting. This experience flips a switch in Schlafly, who, through her intimacy with Republican buzzwords like “limited government” and “states’ rights,” convinces the room to rethink its pro-ERA stance.

Mrs. America may have needed a specific, albeit fabricated, event to showcase Schlafly’s motivation in taking her ERA opposition national, but as for proving herself a formidable foe to Team Feminism, well, the history speaks for itself.

Gloria Steinem (Played by Rose Byrne)

Arguably the world’s most famous feminist, Steinem is Mrs. America’s glamorous, career-girl answer to Schlafly’s traditionalist housewife. A seasoned journalist and activist, Steinem co-founded the all-women-run Ms. magazine and the National Women’s Political Caucus in 1971. However, Mrs. America doesn’t shy away from the idea that Steinem’s star rose on the political scene primarily because she had the right look. Most of the second episode centers on Steinem, during which she is pressured by Representative Bella Abzug (Margo Martindale) to become the face of the women’s movement. As portrayed by Rose Byrne, it’s easy to see why. To quote Rebecca Traister in a 2012 New York Times article, “[Steinem] was young and white and pretty, and she looked great on magazine covers.”

The “Gloria” episode also puts Steinem’s abortion-rights advocacy front and center, without needing to invent a persuasive backstory behind the Ms. editor’s personal connection to the issue. A flashback to 1957 London reveals a 22-year-old Steinem choosing an illegal abortion and moving to India over returning to America and marrying her ex-fiancé. The particulars of the scene are taken from Steinem’s 2015 autobiography, My Life on the Road, which she dedicated to the British physician who performed the procedure. The promises Byrne-as-Steinem makes to the doctor are almost verbatim from the book: “You will never tell anyone my name. And you will do what you want to do with your life.”

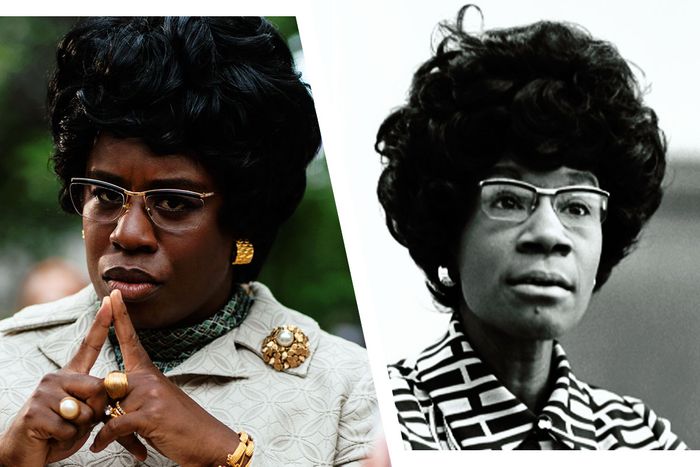

Shirley Chisholm (Played by Uzo Aduba)

In her 1970 memoir Unbought and Unbossed, Representative Shirley Chisholm, the first African-American woman elected to Congress, describes herself as a “maverick.” But being a maverick, whether it was breaking down barriers in government or playing a vital role in getting the Equal Rights Amendment passed in the House of Representatives, wasn’t enough to secure her the Democratic nomination for president in 1972. Because, as highlighted in Mrs. America, she couldn’t even get the support of the National Women’s Political Caucus, or the Congressional Black Caucus, despite being a co-founder of both.

The series’ third episode focuses on Chisholm’s monumental presidential run, in which she was the first African-American woman to seek a major-party nomination. Early on, Chisholm is encouraged to drop out by her Congressional Black Caucus colleagues, as they will be endorsing Senator George McGovern. But the real conflict covered in “Shirley” is the treatment Chisholm received at the hands of the women’s movement.

“I’ve always met more discrimination being a woman than being black,” Chisholm, who spent 14 years in Congress, said in 1982. From the second Uzo Aduba’s Brooklyn congresswoman announces her candidacy for president at the end of the first episode, Mrs. America makes no bones about its intended portrayal of how Chisholm’s gender, rather than race, put her at a disadvantage: A vintage news report of Walter Cronkite has the venerable anchor announcing Chisholm’s run as tossing a “new hat — rather, a bonnet” into the race. Then Martindale’s Bella Abzug spends all of “Shirley” pressing Chisholm to end her campaign so the feminists can consolidate their efforts behind McGovern.

While the series does appear to invent a moment in which Byrne’s Steinem throws Aduba’s Chisholm under the bus at the Democratic National Convention, there are kernels of truth to how the congresswoman, who died in 2005, was treated by her fellow female activists. Steinem, however, still vociferously defends her dubious support of Chisholm’s 1972 presidential run.

Betty Friedan (Played by Tracey Ullman)

Without Betty Friedan, there would be no modern-era feminist movement. Her seminal 1963 book, The Feminine Mystique, encouraged a generation of women to reexamine how they had been unwittingly programmed for a life of housewifery. As a result, the Smith College graduate found herself at the epicenter of the gender-equality fight, helping to start the National Organization for Women in 1966.

By the 1970s of Mrs. America, Tracey Ullman’s Friedan is past her prime, her brash demeanor having become a liability to the National Women’s Political Caucus. Her not-fictional rivalry with Steinem, who is as tactful as Friedan is blustery, also doesn’t help matters. As the series progresses, we witness Friedan’s gradual move into obsolescence, with young girls preferring to admire the hip Steinem instead of a middle-aged divorcée whose only claim to fame, as Martindale’s Abzug quips, is that she “wrote a book ten years ago.” But it’s also no secret that Friedan’s outdated views, specifically regarding gay rights and women of color, didn’t reflect well on the movement either.

In the fourth episode, Friedan disobeys the decision of her pro-ERA colleagues to not engage with Phyllis Schlafly by agreeing to debate the Stop ERA leader at Illinois State University. This debate did take place, in 1973, and the onscreen contentiousness didn’t need any writers’-room embellishment. As depicted in the reenactment, an exasperated Friedan did exclaim that she would “like to burn [Schlafly] at the stake.” While there is no footage available of this debate, Schlafly and Friedan, who died in 2006, held a similar discourse on Good Morning America three years later.

Although Friedan went against the party line by participating in the debate, Mrs. America paints this rebellious choice as a turning point in the ERA fight: Steinem & Co. can no longer dismiss Schlafly and her army of homemakers as a laughable threat.

Jill Ruckelshaus (Played by Elizabeth Banks)

In addition to being a key feminist leader, Elizabeth Banks’s Jill Ruckelshaus functions as Mrs. America’s avatar for the Republicans helpless to stop their party’s shift toward a religious-based, far-right ideology. Ruckelshaus, a pro-choice moderate Republican, was a White House special assistant on women’s rights under the Nixon administration. She was then appointed by President Gerald Ford in 1975 as the head of a presidential commission on women’s rights with the direct intention of getting the ERA ratified; with only four states needed at that point, it felt like a done deal. But it was during this time that Schlafly, whose “Stop ERA” campaign was slowing down, began bringing Evangelical Christians and other religious groups into her fold.

Throughout the first several episodes of the series, Ruckelshaus takes a back seat to her fellow Democrat National Women’s Political Caucus co-founders. But she soon moves center stage as the primary witness of the Republican Party’s transformation from “the party of Lincoln” into one dominated by Schlafly-led conservatives.

The sixth episode features a scripted face-off between Banks’s Ruckelshaus and Blanchett’s Schlafly in a D.C. bar, dramatizing the growing rift within their political party, with Ruckelshaus calling Schlafly on her real endgame: She’s using her “STOP ERA” platform to grow a power base for the intended purpose of electing a conservative president, like Ronald Reagan — or Donald Trump.

Schlafly may not have steered the Republicans away from Gerald Ford or their unwavering pro-ERA stance by the 1976 Republican National Convention, but she planted a seed of discord that would only grow in the coming years: Mrs. America suggests that Ruckelshaus’s husband, William, a one-time Nixon cabinet member, was on the short list to be Ford’s running mate, but was passed over for the anti-abortion Bob Dole because the optics of a pro-choice Second Lady were no longer appealing.

Bella Abzug (Played Margo Martindale)

A three-term Democratic congresswoman from New York, Abzug’s commitment to feminist and civil-rights causes is indisputable. As a young, pregnant lawyer, she represented Willie McGee, a black man in Jim Crow Mississippi accused of raping a white woman, while enduring death threats from white supremacists. Once in Congress, Abzug, who died in 1998, co-authored the Title IX bill, which prohibited sex discrimination at schools receiving federal funding.

In Mrs. America, Abzug is presented as the ERA’s political mama bear. But she also serves to illustrate how increasingly fragmented the women’s movement became throughout the 1970s. This lack of unity may have very well contributed to the ERA’s eventual defeat. Abzug, as portrayed by Martindale, is brusque and outspoken, with the series regularly referencing her ability to intimidate subordinates.

However, in order to amplify tension caused by Phyllis Schlafly’s burgeoning conservative base, the series cooks up a story line in which Abzug grapples with her former radical status, and almost sacrifices an essential gay-rights platform in the process. In 1977, Abzug, having lost her Senate bid after giving up her House seat, is appointed by President Jimmy Carter to head up the National Women’s Conference. When Abzug learns that the Mississippi delegation to the conference has ties to the Ku Klux Klan, she debates removing the gay-rights plank from the platform out of fear. In the end, she keeps it in, but given Abzug’s track record as a LGBTQ ally, this plot device felt contrived, even for a TV drama.