Australian cinematographer Greig Fraser has become one of the go-to directors of photography for productions with immense action and/or visual effects, including Zero Dark Thirty, Killing Them Softly, Rogue One: A Star Wars Story, The Creator, The Batman, and the TV series The Mandalorian, which gave him lots of experience framing and lighting desert vistas full of strange machines and creatures. He brought all of his skills to bear on Denis Villeneuve’s adaptation of Dune and its second chapter.

The shoots were inventive in a number of ways, starting with the texture of the images, which are a hybrid of digital photography and film. As Fraser explains, he and Villeneuve did tests on various film and digital formats prior to making Part One, and Villeneuve decided that the film images, while lovely, had a “nostalgic” look and felt to him like records of things that had already happened, rather than things that were happening right now as the audience watched. He and Fraser ultimately decided to shoot with ALEXA large-format movie cameras, a digital system, then print the finished project to 35-mm. film, which softened the sharpness of the digital images and made them feel old and new at the same time. The result suited Frank Herbert’s saga of the would-be messiah Paul Atreides, which feels ancient but is set 20,000 years in the future.

Analog and digital are stacked like the layers of a cake throughout Dune’s production, which seamlessly merged physical sets and soundstages (at Origo Studios in Budapest, Hungary) and CGI backdrops and effects with actual desert locations (in Abu Dhabi and Jordan) to create panoramas of people, machines, space, fire, and sand. And there are subtle changes in the filming that diverge from the first movie. If you were coming in close to a character, they used slightly longer lenses than they had in the first Dune — but shot from closer up, to make the viewer feel more intimate with the characters. If you were seeing a character from a great distance in relation to huge things, such as an aircraft-carrier-size sandworm or one of the hulking vessels that harvests spice, the most valuable substance in the film’s world, Fraser and Villeneuve tried to shoot with a longer lens and as much space around the character, to make the action appear as though it’s occurring so far away that there was only so much a camera could do to bring it closer. “We wanted to make sure this was not being made for a small screen,” Fraser says. “This was made for the biggest screens that exist on the planet.”

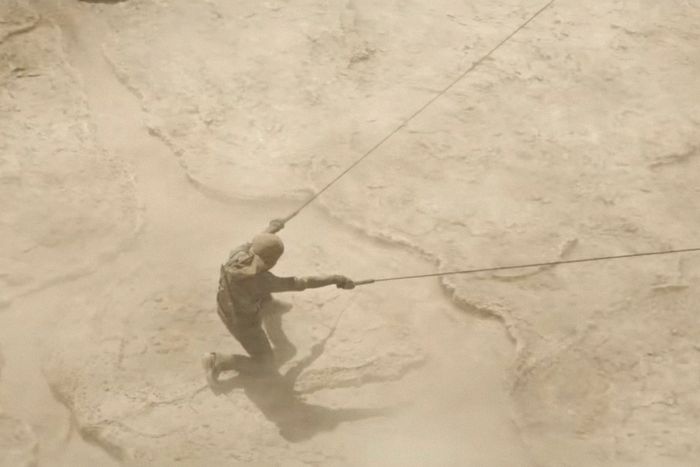

Paul’s first sandworm ride

Fraser knows how to light gigantic things in a way that makes them feel real, whether they’re actual objects, digital simulations, or some combination of the two. He often employs single-source lighting, i.e., all the light in a location seems to come from one direction, such as an overhead light, window, or sunroof. That technique can be seen in the sequence where Fremen tribal leader Stilgar (Javier Bardem) oversees the first attempt by Paul (Timothée Chalamet) to ride a sandworm (known as Shai’hulud) — an event that will determine whether Paul dies or officially becomes one of the Fremen, the desert dwellers of the planet Arrakis. For both Dune movies, Fraser mapped out his idea of “scale” by studying contemporary reference photos of Australian and South American miners “against the big earth-moving machines,” because “for me, it is all about those people.”

In the worm-ride scene, the filmmakers switch between chaotic, sand-choked shots of Paul being pulled up and pushed down into the sand, close-ups and medium shots of the observers, and sweeping shots of both sides of the event that are taken from such distance that the humans seem as tiny as pepper grains. Fraser sums it up as “two perspectives.” One is Paul’s — “in that mêlée of craziness, almost being sucked under the sand, like he’s drowning.” Another is the Fremen’s — “the kin are watching and treating it like a carnival event.” “We know what it’s like to pull out our lawn chairs and our beer hats and watch a parade,” Fraser says. “And they’re doing that, but they happen to be doing it on Arrakis, and they’re watching somebody ride a massive sandworm.”

As for which things are real and which are miniatures or computer-generated: Fraser says Villeneuve had a rule that anything actors interact with in the frame had to be built by the art department. “Anything they’re touching is real. Anything that they’re close enough to that it will impact their existence is real. So we would build as much as we physically could. Obviously when it comes to a sandworm, there’s a limitation to how much you can actually build.” When we’re watching Paul trying to ride and getting pulled down into the sand by the sandworm like Captain Ahab getting dragged into the ocean depths by Moby Dick, we’re seeing Chalamet’s stunt double Lorenz Hideyoshi on a sandpit in Abu Dhabi, with real sand, that was built to look identical to the one they’d used for location footage of the worm ride, but somewhere that could be better controlled. The sandpit had three tubes in it for support. When the tubes were dragged away by three tractor trailers, the dune appeared to “collapse,” dragging Hideyoshi into the abyss. “They effectively created a collapsing sand engine,” Fraser says. That particular shot took “a lot of takes” to get right because it was filmed outdoors and the sunlight needed to be hitting the area from a specific direction, which meant “we only got one take per day.”

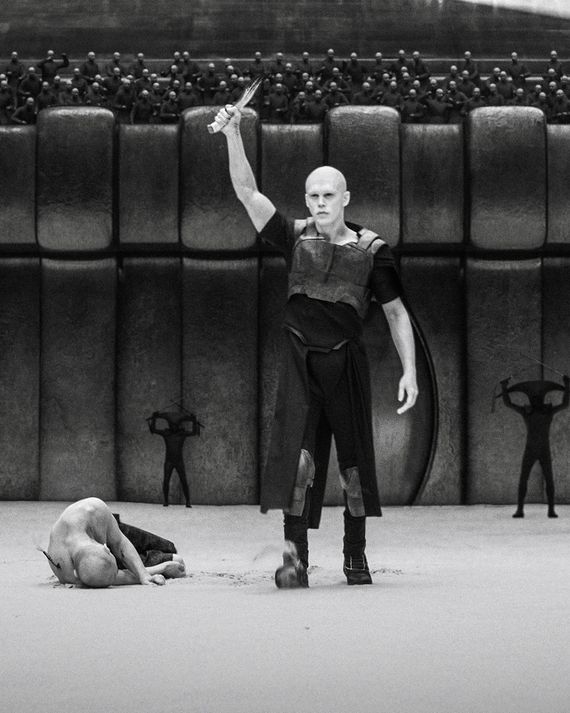

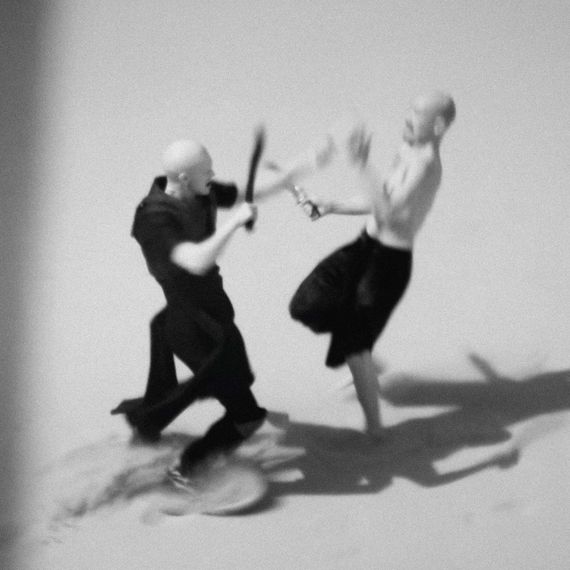

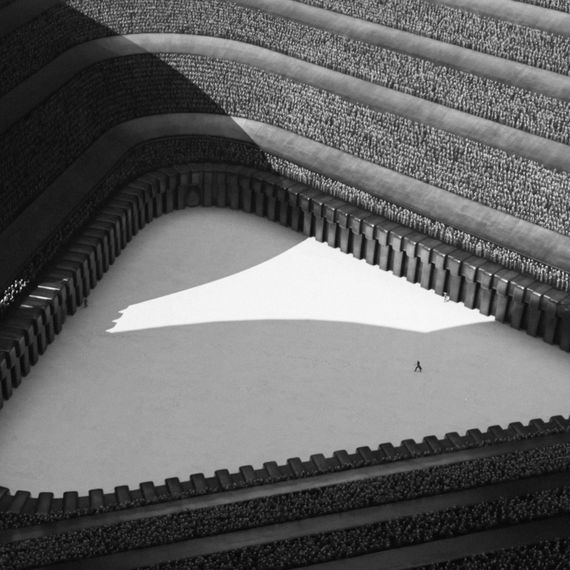

Feyd-Rautha’s black-and-white bloodbath on Giedi Prime

The scenes set on Giedi Prime, headquarters of the pale bald ogres of House Harkonnen, looked bleached-out compared to other Dune planets even in the first movie. But for the scene in Part Two where Feyd-Rautha (Austin Butler), psychotic nephew of Baron Harkonnen (Stellan Skarsgård), kills three House Atreides prisoners in an arena fight, the filmmakers felt it was time for a more visually extreme approach, in part because this scene establishes how physically formidable and sadistic Feyd-Rautha is. The sequence seems like it’s in black-and-white at first glance, or perhaps a color sequence that had all the color drained out in postproduction. But that’s not what it is. There’s something uncanny about it.

That’s because all the shots were taken with an ALEXA camera set to “infrared,” which captures light beyond the spectrum that is visible to the human eye. “It’s the same camera that we shot the film on,” Fraser says, “but we modified it.” The end result is essentially a super-high-resolution version of images captured by modern surveillance devices such as Ring cameras, which get pristine images in pitch-darkness by using infrared light.

Villeneuve told Fraser that he wanted the arena sequence, which was filmed on a soundstage in Budapest, to be instantly interpreted by the audience as being set on Giedi Prime, whose sun doesn’t create any color, not some other planet. “We need to know that we’re not in a gladiator environment in Arrakis. So the sun had to be different.” Fraser and Villeneuve did tests and loved the way the infrared effect looked. “It’s that sort of ghoulish look that you get from that light at night from security cameras, but it’s happening in the middle of the day.” The ground where the combatants confront each other, portions of the walls behind them, and some parts of the arena (including Baron Harkonnen’s luxury box) are sets, while most of the rest is digital, including the seemingly thousands of extras.

The innovative construction and filming of the arena sequence sums up the “old newness” of the film’s aesthetic, reconnecting this franchise with Star Wars, which lifted quite a bit from Herbert, and to earlier pulp influences like John Carter (which also featured scenes of arena combat). It gathers elements that are familiar to audiences — from Herbert’s novels, from films and TV series that have adapted them directly or ripped them off, from desert-adventure and gladiator pictures and Shakespeare tragedies about royal intrigue — and makes them feel eerily original. The end goal, however, remained the same. “As long as you feel a connection with the characters, we’re good.”

Paul and Chani attacked by Harkonnen soldiers

In an early action scene, Paul is protecting Chani (Zendaya) beneath a spice harvester as she fires a shoulder-mounted rocket launcher at Harkonnen soldiers while trying to avoid getting picked off by enemies circling them in an ornithopter, a dragonfly-like aerial vehicle. The underside of the harvester (i.e., the legs and belly) is a set. But when the scene pulls back to adopt a wider perspective, we’re seeing that limited set with CGI on top of it, completing the rest of the vehicle.

When we’re looking over the shoulder of a gunner in the ornithopter firing at Paul and Chani, the shots are taken from inside a Black Hawk helicopter. “We did have a real gunner with a prop gun inside of a Black Hawk, and we shot from inside looking out and looking down,” Fraser says. “So in any of the footage where you see past the gunner to the actors, we were in a real helicopter.” The shots of Paul and Chani down on the ground were taken from a crane that was angled to approximate the perspective of the Black Hawk footage, and then the two elements were digitally merged. One reason the ornithopters characters use to fly across Arrakis seem physically believable when taking off and landing is because, whenever possible, the filmmakers shot actual helicopters taking off, flying, and landing, blowing sand everywhere and making performers’ costumes ripple, then replaced the helicopters with ornithopters during postproduction.

Fraser says that the goal is always to make an image feel so visceral that the viewer doesn’t think about how it was created until later. “In hindsight, you kind of say, ‘Okay, yeah — how did they do that? Did they have a camera operator in the air with a crane?’” The real elements of the image let the filmmakers sell the parts that are conjured from ones and zeros. “That’s why it’s a magic trick. I was showing you my left hand while I was doing the magic trick with my right.”

Correction: An earlier version of this article misstated a difference in the techniques used for shooting characters from up close and far away on Dune and Dune: Part Two.

More on ‘Dune’

- The Empty Impact of Dune: Part Two’s Villain Turn

- Dune: Part Two Is Now Thumping on Max

- The Coiled Ferocity of Zendaya