Rirkrit Tiravanija is an artist without a studio. “I don’t have those expenses and overheads,” he tells me. So he takes what he calls his “studio visits” at Cafe Mogador, the venerably bohemian Moroccan restaurant on St. Marks Place in the East Village. “My favorite place,” he says. Mogador opened in 1983, the same year Rirkrit — everyone just calls him that; the middle r is not pronounced — moved to New York from Toronto, where he had gone to art school. He signed a lease for $290 a month on the same four-room rent-stabilized apartment on East 7th Street, between Avenues B and C, that he still has today (he also has homes in Berlin and his native Thailand). He has kept his costs low ever since, which has enabled him, rare among artists of his renown — a biennial fixture with museum shows around the world who has taught at Columbia for more than 20 years — to be mostly free from having to make art, at least the type that rich people invest in. “I could hit all the right notes,” he says of making expensive objects. “I’d rather not.”

He is most famous for cooking Thai food in art spaces. These communal experiences were deemed revelatory in the 1990s and early aughts, when he first came to prominence. “To have any food in museums is unusual,” notes the performance artist Marina Abramović. “It is forbidden.” Now he is preparing for a long-simmering career retrospective at MoMA PS1 called “A Lot of People,” named after the “materials” needed for his best-known art: conceptually driven, participatory, and ephemeral. There will be cooking at PS1, and tea-making and drinking, as well as the restaging of a work in which he had invited strangers to do the galloping “Shall We Dance” waltz from the musical The King and I (which was set in an exoticized Hollywood version of Thailand). The whole thing will be steeped in ’90s anti-capitalist slacker-refusal nostalgia, at least for those in the know. But this time around, expect TikToks.

In the art world, what Rirkrit does is often categorized as “relational aesthetics,” which emphasizes the social interplay between artist and audience. It has recently been in vogue again, co-opted by pretentious downtown bar owners who want to elevate serving expensive drinks in plywood-walled rooms into the realm of conceptual art. But the curators behind the PS1 show, Ruba Katrib and Yasmil Raymond, are convinced these ideas can be de-co-opted for a generation thirsty for art that defies careerist commerce. “We’re having a crisis of faith,” says Raymond about an art world centered on “value speculation” — which Rirkrit sidesteps. “You can’t really speculate on a dirty electrical wok with noodles on it.”

That doesn’t mean Rirkrit hasn’t sold his art, especially in recipe form, to institutions. But he’s never been a collector’s darling. “You are always working in opposition to what you don’t want to be a part of,” he says.

Rirkrit was born in Buenos Aires, where his father, a Thai diplomat, had been stationed. He learned English at an international school in Ethiopia before being sent to a Catholic school back home in Thailand. There, his grandmother had a garden restaurant. Growing up, Rirkrit liked to watch her cook.

All that moving around left him with an unsettled relationship to his Thai identity. His dream, when he left home for Carleton University in Canada, was to be a photojournalist, which would have enabled him to do more traveling. An art-history class turned him on to Duchamp’s Fountain and the Russian Suprematists, and he transferred to the Ontario College of Art & Design, where he was introduced to the work of Joseph Beuys, who once spent three days in a gallery with a live coyote for a piece.

Rirkrit’s starting point as an artist was his trips to big encyclopedic museums like the Met. It began to bother him that the artistic productions of other cultures were being displayed as examples of pure aesthetics without context. As he said to The Brooklyn Rail back in 2004 about the Thai pots he would see, “There is a kind of misunderstanding of other cultures because you never know how it was used. So then I decided to find a way to address this issue of use or misuse by reusing it. I would say that reusing it basically means to take that antique bowl and put food in it — put life back into it.”

This impulse is in certain ways not that different from the idea behind an early scene in the first Black Panther movie in which the “vibranium” artifacts from Wakanda are taken out of their vitrines and used as weapons again. As Rirkrit puts it, “What I am doing is to take Duchamp’s urinal, put it back on the wall, and piss into it.” Rirkrit’s work, which is so often associated with generosity — the shared food and conviviality, accompanied by his easy, nonjudgmental smile — is not without its possibilities of violence or, at the very least, of disorder. It’s a risk that anybody who works with him must be willing to take.

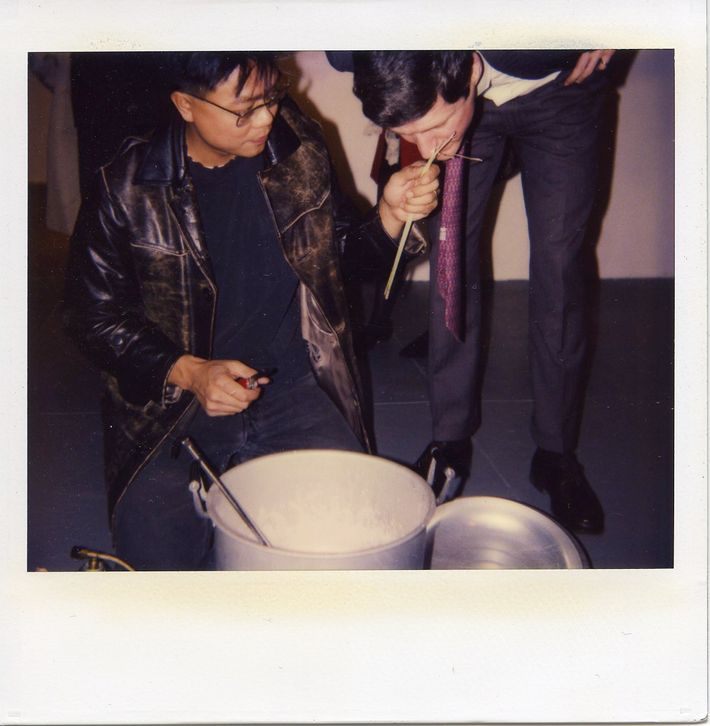

His longest-running partner for his remarkably successful trying-not-to-have-a-conventional-career career has been the gallerist Gavin Brown, who was working at 303 Gallery in 1992 when Rirkrit staged one of his early Happenings, still talked about today by people who were there (many more at least claim to have been). It was called (Untitled) 1992 Free, and for it he had the gallery move the office — the desks and files — out into the exhibition space, putting its functions on display, then he cooked Thai curry in the back, which he gave away to a bemused set of visitors. (The whole thing was restaged at MoMA in 2012.)

“It was shockingly new,” says New York’s art critic, Jerry Saltz, who was there to witness what he describes as a “punk rock” gesture. “He makes a kind of Buddhist modernism. He doesn’t make anything.” It was a revelation for Brown. “The gallery is the illusion,” he recalls realizing.

Free was one of many times over the years that Rirkrit has served curry, but he is still probably most associated with a particular dish he first cooked at Paula Allen Gallery in a performance called Untitled 1990 (Pad Thai). It’s difficult to imagine, but at the time, pad Thai was not a takeout staple. In a knowing gesture that few understood then, Rirkrit used a westernized recipe that was being popularized by an expat Englishwoman who had written a cookbook after visiting Bangkok. Its ingredients included ketchup, and it was made in a West Bend wok, a then-new appliance.

Brown and Rirkrit egged each other on to do memorably reckless things. Like the time in 1999 when Rirkrit reproduced his East Village apartment in Brown’s gallery and left it open for 24 hours a day. People slept there, claimed to have sex there. “I feel encouraged by him to do things which don’t necessarily make sense — or at least business sense,” says Brown. “If they make business sense, they don’t make art sense.” (His gallery closed in 2020.) In 2015, they opened Unclebrother, a restaurant and gallery three hours upstate in Hancock in a former car dealership. “It’s this strange lark we started,” says Brown. “It doesn’t make money because it’s out of reach.”

For the first month of the show at PS1, pad Thai (ketchup version) will be cooked in West Bend–style woks and served — not by Rirkrit but by a group of his current and former students from Columbia’s M.F.A. program. That this re-creation will be performed by actors and on a stage will emphasize its artifice and make what is going on here more clearly “art.”

At a rehearsal I attended in September, Rirkrit’s instructions to the students were to cook until the ingredients ran out. One young man, Dylan, was designated to represent the artist, and he began the “play” — which is what Rirkrit calls these restagings — by unpacking and prepping the ingredients. Other students, playing the gallery guests, talked casually in clumps on either side of the stage, as if they were at an opening. Gradually, the “gallerygoers” joined in to help Dylan, just as Rirkrit tells me his friends did back in the day. “You have to cook with more confidence,” Rirkrit told Dylan. “Tell the other people what to do.”

One of the students asked what they were supposed to say if an actual PS1 museumgoer asked what was going on. “Well, this is some sort of an art piece,” suggested Rirkrit. “People thought I was the caterer.”

“We cook and eat a lot in class,” says Anna Ting Möller, one of his former students who had agreed to be part of the exhibition. (They all get paid.) “We went to Unclebrother when we didn’t know each other at the beginning of class. That’s how we bonded: standing together in the kitchen.”

Several of his other past works will also be revisited: a Ping-Pong table you can play downstairs that is a reference to a dissident artist named Július Koller, who set up a table-tennis club in Bratislava to circumvent Communist rules against unsanctioned gatherings; a re-creation of one of Brown’s galleries on Broome Street; a plywood space of the same dimensions as a studio where Rirkrit and his friends used to practice music on Avenue A, with instruments for museumgoers to play.

Many different things will happen there on different days. Which show you see will depend in part on which day you come. “There will be an element of chaos to it,” says co-curator Katrib.

Rirkrit’s seminar at Columbia is called Making Without Objects and is something of a legend among his students and fellow teachers. “When he came up with it, we thought he was messing with us,” Tomas Vu-Daniel, another professor at Columbia’s M.F.A. program, tells me. He jokingly admits he sometimes “hates” Rirkrit for how popular he is among his students, who often start out befuddled but end up calling his class their favorite.

Rirkrit tells me that he recently asked them “to make a very small sculpture, like an inch by one inch, no bigger than that,” and to bring it to the Met and “insert it in the collection. They watched the interactions people had with it, whether they took it away or whatever, and documented it.” The idea was for them to think about “the context they were working in and the audience that was in the context.”

So much of what is meaningful to Rirkrit is, I realize, about his teaching. (“I am a little notch they have to trip over on their way to their M.F.A.,” he says.) “The art world has changed. The way we look and think about art or the reason for it has changed,” he says. “Let me give you a little example. The idea that young Asian people would take up art-making used to be strange. Because, of course, unless you grew up in a crafts family and you were sitting in the little temple house or whatever sculpting, most people are aspiring to be other things, but now art is one of the aspirations. It’s become that also because the parents accept that. Why do they accept that? Because they see it as a profession now. You know? That to me is the opposite of what art-making should be.”

There seems to be a restlessness to Rirkrit that is hard to square with his never-ever-stressed equanimity. Early in his career, he was married to the painter Elizabeth Peyton. “They were a legendary romantic pair,” recalls Brown, who represented them both, but she was studio-based while he “was the poster child of the post-studio artist.” Peyton and Rirkrit remain close. “I think it’s been a refrain he’s been saying for a while: ‘I’m going to stop traveling all the time,’” Peyton says. “But I don’t think it’s in him to.” She continues, “The whole world is not a huge place for him.” Since August, he has been in Thailand (doing preparation work as a director of its next Biennale), Korea, and Japan.

And then back to New York to teach and set up this survey of things past, conjured again with the hope, perhaps, of nudging the present, even the future, away from thinking about art as the creation of an asset class for investment instead of as a struggle for personal freedom.

Or maybe he’s just putting the urinal back on the wall and inviting us all to piss in it.