Bad Bishop

/Bad Bishop

Bad Shepherds: The Dark Years in Which the Faithful Thrived While Bishops Did the Devil’s Work, by Rod Bennett, Sophia Institute Press, Manchester, New Hampshire, 2018

Fuerchte dich nicht du Kleine Herde by Gabriele Kuby

Kisslegg: FE Medienverlag, 2023

REVIEWED BY DR. E. MICHAEL JONES

Confronted with chaos in the Church, a number of writers have stepped forward and offered their explanation of what went wrong and what needs to be done. Rod Bennnet’s book Bad Shepherds: The Dark Years in Which the Faithful Thrived While Bishops Did the Devil’s Work is a recent example of this genre. Bennett claims that he has written “a history with a healing purpose, aimed at binding the wounds being inflicted on modern Catholics by their own bad shepherds.”[1] In order to make his point, Bennett proposes a Manichean dichotomy according to which the light of the laity illumines the darkness of the bishops. Four legs good, two legs bad is nuanced when compared to the invidious comparisons which inform Bennett’s book. During the Arian crisis, we are told:

God’s lowly laity began to shine. The simple, dutiful man or woman in the pew was never, in any great numbers, at all fooled by any of this. The truth of the matter had been plain to them from the beginning: Arianism was a political scheme dreamed up by politicians for purposes of their own; nothing more, nothing less. Laypeople were the guinea pigs; Constantius and his ilk were the experimenters.[2]

Constantius, in case you didn’t know, was the Roman emperor at the time, a fact that Bennett fails to explore throughout his book. The bad bishop, it turns out even in the examples that he gives, have one thing in common, and that is weakness when confronted by imperial power. The bishop is not the main actor in this story; the prince is.

Rod BennetT

As an alternative to the bad bishop, Bennett creates the myth of the pious laity. At virtually every crisis in the Church, “the laity shone—at a time when clerical spines needed stiffening badly.”[3] During the Arian crisis, “the laity—the blessed laity—now sheep without a shepherd, as it were, once again, prayed their prayers, worked their works of compassion, continued their patient imitation of Christ ... and kept on keeping on”[4] while at the same time praying “a pox upon all these fools and knaves,” who happened to be their bishops.[5] The saviors of the Church during the Dark Ages, were: “The men and women who responded to the calls of Columba, of Benedict, of Boniface, and of other monastics must, after all, have come originally from the ranks of a pious laity.”[6]

The fact that Bennett claims that the heroes of this story “must have come from the laity” exposes the conjectural nature of his premise, as he himself admits:

No Ernie Pyle has immortalized his story, but orthodoxy’s “G.I. Joe”—the regular Western layman—must have existed during the Dark Ages, or there would have been nothing left to reform when Gregory VII came along.[7]

The term laity in Bennett’s book is a category of the mind which marshals the historical facts to a foregone conclusion, which has more to do with cultural categories in the United States than the structure of the Church throughout the ages.

Rod Bennett is a convert who hails from East Tennessee, where ministers handle snakes and every man is his own priest. The Church welcomes converts, but as Jewish converts like Dawn Goldstein, Rebecca Bratten Weiss, and others have shown, converts often bring baggage with them which distorts their understanding of the religion they have newly adopted. In Bennett’s case, echoes of Whig history, the Black Legend, American exceptionalism, and other Protestant concepts rear their heads and determine the course of the discussion. John Maynard Keynes said politicians invariably channeled the thoughts of some defunct economist. The same sort of unconscious bias is responsible for the bad bishop/good layman dichotomy which deforms the history it sets out to interpret in Bennett’s book.

Bennett dragoons “Catholic laypeople” like “Chaucer, Dante, Giotto, Petrarch, Marco Polo, St. Louis IX, and Richard the Lionheart” into a narrative in which he describes the Middle Ages as “the age of Magna Carta,” an era which displayed “the beginnings of self-government”[8] in a way dear to the heart of Englishmen but which distorts the role of bishop as defined by the Church.

The first bishops were appointed by Christ. They were not chosen democratically by the laity in the manner of lesser nobility extorting rights from the crown, as was the case in “the age of Magna Carta.” This beginning determined what was to follow in the Church. The apostles, who were “appointed as rulers in this society, took care to appoint successors.” The laity, in other words, were completely excluded from a process which began with Christ and continued with those chosen by Christ choosing their successors down to the present day. It is this apostolic succession which anchors the Church in Christ, and it is through this succession that the patrimony of faith gets handed down from one generation to the next. The structure of the Church is thus hierarchical and not democratic.

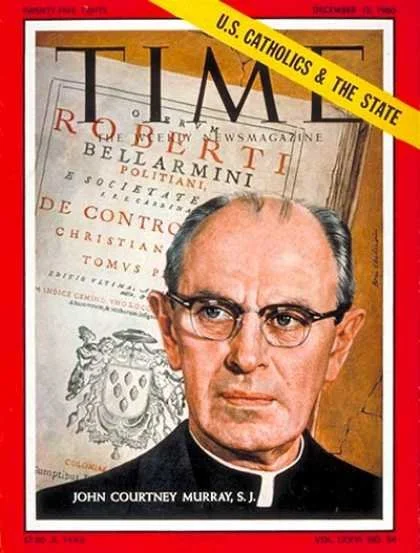

The Second Vatican Council, convened at the dawn of the American empire, took place under its shadow, and double agents like John Courtney Murray tried to get the Council to import alien principles like the separation of Church and state into Dignitatis Humanae, but they could not impose democratic principles on a hierarchical Church, led by bishops, because Christ:

willed that their successors, namely the bishops, should be shepherds in His Church even to the consummation of the world. And in order that the episcopate itself might be one and undivided, He placed Blessed Peter over the other apostles, and instituted in him a permanent and visible source and foundation of unity of faith and communion. And all this teaching about the institution, the perpetuity, the meaning and reason for the sacred primacy of the Roman Pontiff and of his infallible magisterium, this Sacred Council again proposes to be firmly believed by all the faithful. Continuing in that same undertaking, this Council is resolved to declare and proclaim before all men the doctrine concerning bishops, the successors of the apostles, who together with the successor of Peter, the Vicar of Christ,[9] the visible Head of the whole Church, govern the house of the living God.

The apostles were “appointed as rulers in this society,” and they “took care to appoint sucessors.”[10] The divine mission which has been “entrusted by Christ to the apostles will last until the end of the world,” but its form of governance will not change.[11] Bishops are chosen by other bishops, who are chosen by other bishops, going all the way back to the first bishops, or apostles, who were chosen by Christ. This is a top-down operation. It does not rise from the bottom, as the democratic process operates, or should operate. In order to carry out their task, the bishops receive “a special outpouring of the Holy Spirit,” which is “transmitted” by “Episcopal consecration” from one bishop to another.

John Courtney Murray

Ignoring Church documents on the role of a bishop, Bennett claims that “Bad shepherds, in fact, were the chief obstacle to reform in those days; most of the serious reform efforts were commenced by laypeople, secular leaders, and, sometimes, religious monks and sisters.”[12] In this passage, Bennett is referring to the 15th century, the Avignon papacy, and the condemnation of Jan Hus at the Council of Constance, which was certainly a scandalous era, but he then goes on to claim that the same thesis applies to the Reformation, which was a creation of bad bishops as well. In order to maintain that thesis, Bennett tries to foist an essentially Protestant and totally naïve understanding of Luther on his readers.

Bennett’s historical surveys often say the opposite of what he thinks they say. A good example is his claim that bad bishops were responsible for the Reformation. This involves a naïve portrayal of Luther as a sincere but misunderstood Catholic reformer, a view which may be conditioned by residual Protestantism.

In addition to sins of commission, Bennett commits a glaring sin of omission by not mentioning the Council of Trent. The group which put an end to the threat of the Reformation, regained two-thirds of the territory lost to the Protestants in the 16th century, and inaugurated what is arguably the greatest come back in the history of the Catholic Church was made up entirely of bishops. Why didn’t Bennett mention the Council of Trent? We don’t know, but we can only assume that he omitted it because it contradicted the bishops bad/laity good thesis which informs his book.

Bennett also ignores the evidence which he does bring to bear on the Reformation, evidently unaware that it too contradicts his bishops bad/laity good thesis. As I have said many times, the Reformation was a looting operation, whose main actors were the lower aristocracy in both England and Germany who could not resist the temptation to steal Church property which the Reformation provided. Bennett cites William Cobbett, who writes:

Religion, conscience, was always the pretext, but in one way or another, robbery, plunder was always the end. The people, once so united and so happy, became divided into innumerable sects, no man knowing what to believe; and, indeed, no one knowing what it was lawful for him to say; for it soon became impossible for the common people to know what was heresy and what was not.[13]

This passage is undeniably true, but it hardly constitutes praise for the laity, who are portrayed as confused sheep without a shepherd and unable to comprehend the magnitude of what was happening. Confronted with facts like this, Bennett retracts his thesis and admits, in tacit recognition of the reforms of Trent, that “For every pope or cardinal who went bad, there are ten at least who poured out their lives for my salvation and yours.”[14] The laity, in other words, cannot save the Church in spite of the bishops. In order to be effective, “the faithful must cling to their bishop, as the Church does to Christ.”[15]

This, however, is not the program which Bennett proposes in his book.

Bennett concludes that “this story of the bad shepherds has taught us the slow, steady, but enormous power of God’s blessed laity.”[16] If the laity can’t do it, no one can. Only the laity can serve as “a good counterbalance to the failings of the bad shepherds.” Only they can “right the bark of Peter and clean the Augean stables.”[17] Bennett even urges the laity to leave the Church. The laity “can empty the churches of known collaborators in the cover up. . . . Let them preach to vacant pews. We can receive our lessons and our sacraments elsewhere: an irregularity, to be sure, but these are irregular times.”[18]

At this point, the cure begins to look worse than the disease. Schism is not the cure for heresy or any other ill in the Church. Schism, according to St. Augustine, is the refusal to join in the communion of the faithful out of fear of contamination, and the prime example of schism in his day and time was the Judaizing sect known as the Donatists. No offense in the Church is grave enough to warrant separation from the communion of the faithful and the sacraments dispensed by her ministers. If Bennett knows this, he should tell us. If he doesn’t know this, he shouldn’t be writing books which flatter the laity only to lead them astray.

Bennett’s solution to the problem of bad bishops has a particularly American flavor, resembling the Boston Tea Party more than the plenary councils of Baltimore:

Many church functions – many of the ones that have gone most neglected, in fact, such as remedial catechesis and adult formation – likewise do not require the hand of a sacerdotal minister. The men and women who returned Athanasius to his see prayed in their own homes long prayers for strength and deliverance, unassisted by clergy. We’ve heard talk about “the hour of the laity” for decades; now seems the time to make it more than talk. . . . Those times of duty have come. A time to purify the Church ourselves, a time to tell the clergy (reverently) to “lead, follow, or get out of the way.” This time, we don’t want it over; not until the rats are out of the barn with the barn still standing – so that we can all go back in it again to gather the harvest.[19]

Bennett then unwittingly invokes the issue of trusteeism, as when he writes that “buildings that have been put up and paid for by the laity can have new locks installed; and yes, faithless priests can be sent back to the bishop.”[20] It’s not that simple. Bennett’s glib suggestions indicate an ignorance of Church history and any understanding that the Church has already been down this road and decided in favor of the bishops and against the laity, especially in 19th century America, where ethnic Catholic churches refused to accept priests from other ethnic groups as pastors. According to the Encyclopedia Britannica:

Crises thus arose when trustees invoke civil law to dismiss unpopular pastors, sometimes because they were from different ethnic backgrounds than their parishioners. Trusteeism spread across 20 states in the East, South, and Midwest. Occasionally, trustees joined with anti-Roman Catholic groups (i.e., the Know-Nothing Party) to encourage civil legislation favouring their cause. . . . Trusteeism faded as American bishops gradually reasserted their prerogative under church law to appoint pastors through the use of legislation passed at a series of church councils in Baltimore. The controversy caused the bishops thereafter to be wary of lay leadership in parish administration.[21]

Whenever dissension arose, as was often the case, between Polish laymen and Irish bishops, the Holy See invariably sided with the bishops. Both Pope Pius VII and Pope Gregory XVI “vindicated the rights of the Church against the pretensions of the trustees,” with the latter pope claiming that “the office of trustees is entirely dependent on the authority of the bishop, and that consequently the trustees can undertake nothing except with the approval of the ordinary.” The Third Plenary Council of Baltimore confirmed the judgment of the popes, claiming that “in case of disagreement between the trustees and the rector, the judgment of the bishop must be accepted.”[22]

Council of Trent 1545-1563, Museo del Palazzo

Bennett’s difficulties in forming the right categories are compounded by his folksy style, which leaves his book marred by slang that never elucidates and often times confuses the issue, as when he tells us that the fifteenth century was a “dumpster fire.”[23] In describing the Reformation, Bennett tells us that when Eck tried to bring the Germans around, he “was almost lynched. The people wouldn’t have any of his bull — they took it away from him and burned it.”[24] In describing the support which Luther received from the German people, Bennett tells us that “Metaphorically, the whole German Volk took Luther onto their shoulders like the quarterback who just tossed the game-winning pass.”[25] Isn’t “Volk” another word for laity? If so, Bennett just refuted his own thesis.

Bennett’s slang repeatedly comes back to bite him. After the pope condemned him:

Dr. Martin Luther’s career as a Catholic university professor was over. The pope had called him a fool, and there’s just no recovering from that in Luther’s line of work. For Luther now, it was either beg in the streets or double down and take the whole thing to another level. His many fans practically made the decision for him.[26]

Does “many fans” mean the laity? If so, Bennett once again refuted his own bishops bad/laity good thesis. If not, Bennett should be more precise in explaining who was responsible. The same is true of the people Bennett refers to as “Luther’s supporters,” who “egged him on—drove him, like a stunt performer, to add ever more dangerous feats to his act.”[27]

Who are these people? Are they “das Volk”? If so, they are the laity who should have rescued the German Catholic Church from its bishops. Unfortunately, they were no better than the archbishop of Brandenburg, the man Bennett has appointed as bearing responsibility for the Reformation:

And it was only when Albert—yes, that same bad shepherd, the archbishop of Brandenburg, who needed to repay the three hundred thousand ducats he had borrowed to get a waiver for holding three bishoprics at once!—disdained to return his call, so to speak, that Luther got riled. He distributed the Ninety-Five Theses publicly (using the recently invented Gutenberg printing press, by the way) and challenged all comers to debate.[28]

By this point in his narrative, the bad bishop thesis, not the facts he marshals, determines the outcome of Bennett’s argument. Bennett then cites Hilaire Belloc and William Cobbett, both of whom claim in Belloc’s words that “the driving power behind” the Reformation was “the opportunity for loot.” But Bennett seems unaware that he has refuted his bad bishop thesis. Or are we to believe that the bishops looted their own churches? The idea is absurd. It was the thieving aristocracy who were the driving force behind the Reformation, which was nothing more than a looting operation, completely without theological justification in England, and with Luther’s self-serving theology providing the justification in Germany. R. H. Tawney gave us the best explanation of the relationship between loot and piety in England when he wrote, “The upstart clergy had their teeth in the carcass, and they weren’t going to be whipped off by a sermon…”

[…] This is just an excerpt from the May 2024 Issue of Culture Wars magazine. To read the full article, please purchase a digital download of the magazine, or become a subscriber!

Articles:

Culture of Death Watch

Gamer Life by Brother Michael

NATO’s War Against Russia by Luis Alvarez Primo

Features

The Failed Quest for American Identity by Dr. E. Michael Jones

The God of the Cubicles: Why Sola Scriptura is not Scriptural by JP

Reviews

Bad Bishop by Dr. E. Michael Jones

(Endnotes)

[1] Rod Bennett, Bad Shepherds: The Dark Years in Which the Faithful Thrived While Bishops Did the Devil’s Work, (Sophia Institute Press, Manchester, New Hampshire 2018), p. 8.

[2] Bennett, Bad Shepherds, p. 19.

[3] Bennett, Bad Shepherds, p. 26

[4] Bennett, Bad Shepherds, p. 29.

[5] Bennett, Bad Shepherds, p. 53.

[6] Bennett, Bad Shepherds, p. 58.

[7] Bennett, Bad Shepherds, p. 58.

[8] Bennett, Bad Shepherds, p. 59.

[9] Pope Paul VI, Lumen gentium, Nov. 21, 1964, Vatican.va, https://www.vatican.va/archive/hist_councils/ii_vatican_council/documents/vat-ii_const_19641121_lumen-gentium_en.html

[10] Lumen gentium, 20.

[11] Lumen gentium, 20.

[12] Bennett, Bad Shepherds, p. 59.

[13] Bennett, Bad Shepherds, p. 103.

[14] Bennett, Bad Shepherds, p. 139.

[15] Lumen gentium, 30.

[16] Bennett, Bad Shepherds, p. 141.

[17] Bennett, Bad Shepherds, p. 141.

[18] Bennett, Bad Shepherds, p. 144

[19] Bennett, Bad Shepherds, pp. 144-5.

[20] Bennett, Bad Shepherds, p. 144.

[21] “trusteeism,” Britannica, https://www.britannica.com/topic/trusteeism

[22] “Trusteeism,” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Trusteeism

[23] Bennett, Bad Shepherds, p. 67.

[24] Bennett, Bad Shepherds, p. 93

[25] Bennett, Bad Shepherds, p. 87.

[26] Bennett, Bad Shepherds, p. 90.

[27] Bennett, Bad Shepherds, p. 92.

[28] Bennett, Bad Shepherds, p. 86.

[29] Bennett, Bad Shepherds, p. 94.

[30] Bennett, Bad Shepherds, p. 94.

[31] Gabriele Kuby, Fuerchte dich nicht du Kleine Herde (Kisslegg: FE Medienverlag, 2023), p. 11. All translations from the German are mine.

[32] Lumen gentium

[33] Kuby, p. 24.

[34] Kuby, p. 25.

[35] Kuby p. 15.

[36] Kuby, p. 13.

[37] Kuby, p. 14.

[38] Kuby, p. 16.

[39] Kuby, p. 18.

[40] Kuby, p. 39.

[41] Kuby, p. 42.

[42] Kuby, p. 40.

[43] Kuby, pp. 27-9.

[44] Kuby, pp. 32-33.

[45] Kuby, p. 19.

[46] Kuby, p. 20.

[47] Kuby, p. 41.

[48] Kuby, p. 60.

[49] Kuby, pp. 44-5.

[50] Kuby, pp. 72-3.

[51] Kuby, p. 78.

[52] Kuby, p. 14.

[53] Kuby, p. 22.

[54] Kuby, pp. 23-4.

[55] Kuby, p. 30.

[56] Kuby, p. 31.

[57] Kuby, p. 34.

[58] Kuby, p. 85.