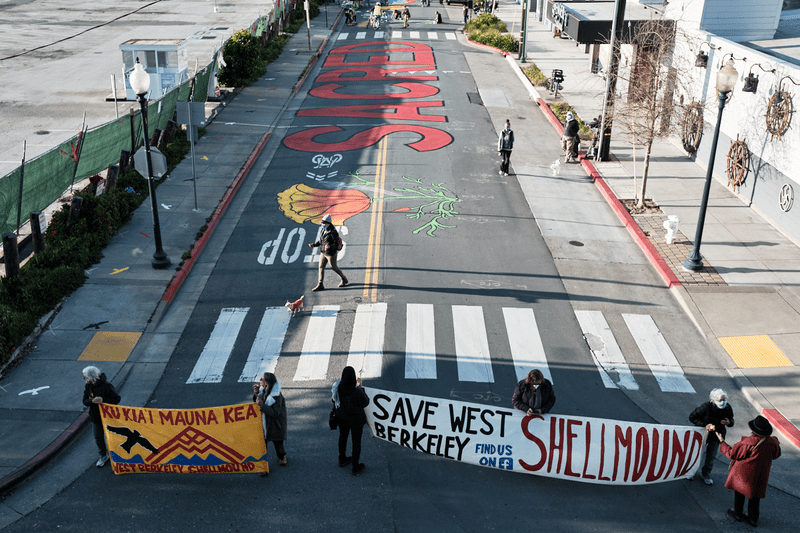

The March 2024 announcement from the Berkeley City Council that it had concluded eight years of commission reviews, demonstrations, lawsuits and ultimately negotiations to protect and preserve the West Berkeley Shellmound sent shockwaves throughout Berkeley and beyond. The two-acre parcel, paved over for a parking lot for the former Spenger’s Fish Grotto restaurant, was purchased from an owner who sought to develop it as a residential/commercial complex, for $27 million dollars, of which the city contributed $1.5 million. The bulk of the funds, $25.5 million, were raised by Sogorea Te’ Land Trust, under the leadership of Corrina Gould, chairperson of the Confederated Villages of Lisjan, a local Ohlone tribe whose roots in Berkeley go back millennia.

The West Berkeley Ohlone Shellmound and Village Site is one of the most significant archeological sites in the Bay Area, generally acknowledged as the site of the first human habitation on the shores of San Francisco Bay. It was a ceremonial center that rose up 20 feet, extended several hundred feet in length and could be seen from miles away. It contains a record of dramatic environmental and cultural change over thousands of years.

Although the Shellmound has been leveled, plundered by early settlers who carried off mortar, pestles, projectile points (arrowheads), fish hooks, bone awls, disk beads, charmstones and sometimes human remains as souvenirs, the site still contains objects of cultural significance in the soil beneath the asphalt, and is important enough to have been designated as eligible for the National Register of Historic Places in 2003. An additional landmark is the hard-won deal that is the largest “land back,” urban sacred site victory in California history.

While the commercial value of the site is obvious, the cultural significance of the place and its hold on the imagination of Native peoples is not as apparent when viewing the dusty lot with its nearby train tracks and the hubbub of the Fourth Street corridor. The planned development had much to offer the city — increased tax base, much needed housing — but the invigorating vision that Sogorea Te’ proposes in its stead is a thousand times more valuable by any measure: gardens, ceremonial spaces, daylighting of Strawberry Creek, a cultural center with educational exhibits and programs. The return of a part of their original lands to the Ohlone people represents an historic turning point, not just for Berkeley but for the entire country. Finally, the Indians win one.

In addition to the thousands of hours of hard work by Bay Area Indians and their allies, this monumental land rematriation is yet another example of Berkeley’s decades of progressive actions and dedication to social justice. We are not only the home of the Free Speech Movement and curbside recycling, we were also the first city to recognize Oct. 12 as Indigenous Peoples’ Day. We have a history and commitment to righting wrongs. And the desecration of Berkeley’s Shellmound, a rich repository of shells and ritual objects from a sacred space that was used for thousands of years as a burial and ceremonial site, was an egregious wrong that went unnoticed and uncorrected for generations. Much of its archeological treasure, some of which is now housed in UC Berkeley’s Phoebe A. Hearst Museum, was removed in the late 19th and early 20th centuries to line railroad beds and for other construction purposes.

Although traditional native life is not a utopia, returning the land back to local Ohlone peoples creates an opportunity for something exceptional to happen. Once the additional funds are raised to complete this almost miraculous rematriation project, the site will draw many new visitors to Fourth Street, a prospect not lost on quite a few of the nearby merchants who have supported the project. Until that day, I invite you to visit this still-sacred site and to imagine the vibrant village it once was, at the spot where a beautiful, flowing, Strawberry Creek emptied into the Bay and to also envision the revitalized cultural center it will become, honoring our heritage and — as the women-led Sogorea Te’ Land Trust calls on us to do — healing and transforming the legacies of colonization, genocide and patriarchy.

The city’s recent actions in returning this small, sacred piece of Berkeley to the Ohlone make me proud to be a resident.

The Berkeley community is invited to join me at a joyous celebration of the Shellmound Victory on Saturday, July 13, from 4-8 p.m. at the Shellmound site at 1900 4th Street. The event is being hosted by the Sogorea Te’ Land Trust and the Confederated Villages of Lisjan Nation. All are welcome! (Note: You are encouraged to bring a folding chair if you would like to sit and a water bottle to stay hydrated.)

Malcolm Margolin is the founder of Heyday books and the California Institute for Community, Art & Nature and author of The Ohlone Way: Indian Life in the San Francisco-Monterey Bay Area and other books about Native Californian history.