I must obey the inscrutable exhortations of my soul. My mandate also includes weird bugs.

Tam multa, ut puta genera linguarum sunt in hoc mundo: et nihil sine voce est.

Monday, May 2, 2022

My mandate also includes weird bugs

Sunday, August 22, 2021

The question is not, Can we suffer? but, Can we learn?

a full-grown horse or dog is beyond comparison a more rational, as well as a more conversable animal than an infant of a day, or a week, or even a month old. But suppose the case were otherwise, what would it avail? The question is not, Can they reason? nor, Can they talk? but, Can they suffer?

Thursday, June 3, 2021

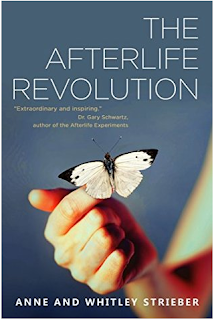

A butterfly Mason?

I wonder how common this association is? I know Aristotle used the same Greek word to refer both to the soul and to the cabbage butterfly. (By coincidence, this same species of non-moth appears to have been chosen by Strieber's entomologically confused cover illustrator.)

Suleiman-bin-Daoud laughed so much that it was several minutes before he found breath enough to whisper to the Butterfly, "Stamp again, little brother. Give me back my Palace, most great magician." . . . So he stamped once more, and that instant the Djinns let down the Palace and the gardens, without even a bump.

The cats' fear didn't make sense to me at all. I decided there must be some animal outside, perhaps a deer. I returned to Dr. Gleidman's essay.I read the following sentence: "The mind is not the playwright of reality."At that moment there came a knocking on the side of the house. This was substantial noise, very regular and sharp. The knocks were so exactly spaced that they sounded like they were being produced by a machine. Both cats were riveted with terror. They stared at the wall. The knocks went on, nine of them in three groups of three, followed by a tenth lighter double-knock that communicated an impression of finality.

I cannot know if this was intended, but the knocks reflected a tradition in Masonry where when someone is elevated to the 33rd Degree, they knock in this way on the door of the hall before being admitted.

He repeats this assertion in The Super Natural.

Also, when entering the thirty-third degree, a Mason must knock on the door of the lodge nine times in three groups of three.

I know basically nothing about the higher degrees of Masonry, but certainly "three distinct knocks" is a thing, and it wouldn't be surprising if they sometimes did three groups of three. Anyway, the point here is that Strieber, just like me today, (1) saw his cats behaving strangely, (2) assumed it was because of an animal outside, and then instead (3) observed something which he connected with Masonic ritual.

Monday, April 12, 2021

Noah's eyes

|

| Blue irises and white sclerae |

This is from Mauricio Berger's Sealed Book of Mormon (Sealed Moses 4:3). Little things like this have a way of capturing my imagination.

And Lamech lived a hundred and eighty-two years, and begat a son, and named him Noah . . . and when he saw the newborn child, he perceived that his eyes were different, and he was afraid that Noah would be the son of a watcher, but the Spirit of the Lord rested on Lamech, comforting his heart by making him know that he was not a descendant of the watchers, but it was the beginning of a new human progeny.

In context, watcher refers to angels that were mating with human women, as recounted in the Book of Enoch and alluded to in Genesis 6. Noah's eyes were sufficiently "different" that his father, Lamech, feared he might not be fully human -- but of course all humans alive today are supposed to be the descendants of Noah, so "Noachian" eyes -- eyes of a type like those of the watchers, but unknown among antediluvian humans -- must be commonplace, perhaps even universal, among modern humans.

My first thought was that Noah must have had white sclerae. This trait is now so universal among humans that the sclera is commonly called the "white of the eye" -- but our closest relatives, the chimpanzees, have black sclerae (darker than the iris), and so our distant ancestors may well have had all-dark eyes as well. Interestingly, bonobos have sclerae which, while not as white as our own, are lighter than the iris. Among gorillas and orangutans, sclera color varies from individual to individual, much like iris color in some human populations, and may be either lighter or darker than the iris.

Another obvious possibility is that Noah had "blue eyes" -- meaning blue irises. When we think of "eye color," we think of the iris, taking it for granted that the sclera is always white. Among monkeys and apes generally, though, it is sclera color that is variable, while irises are almost universally brown. I am open to correction by any primatologists among my readers, but I believe it is correct to say that (excluding albinos from consideration) no other monkey or ape has blue eyes; certain lemurs are our closest blue-eyed relatives, and blue eyes in lemurs are genetically different from those in humans and apparently evolved independently. It seems quite likely, then, that early humans were all brown-eyed, and that blue eyes appeared later.

If we are all descended from blue-eyed Noah, though, why do so few of us (8 to 10%) have blue eyes? Well, Noah was apparently a mutant, so we can assume that neither his wife nor any of his three daughters-in-law had any blue-eye genes. Since blue eyes are recessive, all of his children and grandchildren would have been brown-eyed. His great-grandchildren (assuming they were the product of cousin-marriages among his grandchildren) would have been 6.25% blue-eyed -- reasonably close to the modern percentage.

Thus far I have been trying to guess the nature of "Noachian" eyes by thinking of ways (some) human eyes differ from those of our nearest relatives, but we are also told that Noah's eyes were like those of a watcher. Are there any hints in old books as to what the watchers' eyes looked like? Nothing in the Bible or Book of Enoch comes to mind, but aren't the Greek gods -- heavenly beings that came down, mated with human women, and begat the "mighty men which are of old" -- likely the same beings as the watchers? And we know from Homer that Athena, at least, had distinctive eyes. Her stock epithet is γλαυκῶπις -- which could be calling her eyes either "bright, gleaming" or "blue-green, blue-gray." I do not believe Homer gives any of his human characters eyes of this sort. Athena's epithet leads us back to the two possibilities I have already discussed: Athena's eyes may have been blue or gray, or they may have been unusually "bright" because her sclerae were white rather than black.

⁂

Why bother writing a post like this, about what Noah's eyes might have been like if a certain obviously bogus book were actually true? Because -- and I am quite confident in saying this -- if I don't, no one else will!

Wednesday, January 13, 2021

Q*bert

Saturday, November 28, 2020

On vegetarianism and animal welfare

As twenty cannibals have hold of you

They need their protein just like you do

This town ain't big enough for the both of us

And it ain't me who's gonna leave

-- Sparks

I've been thinking about vegetarianism a bit recently, due to the recent conversion of a few of my closest associates to that cause. Here are some thoughts.

⁂

Consider the werewolf.

One of the books I read and reread a zillion times as a child was The Werewolf Delusion by Ian Woodward. It includes a bit about ceremonies for turning oneself into a werewolf, and one of the spells to recite is (don't try this at home!) "Make me a werewolf! Make me a man-eater. Make me a werewolf! Make me a woman-eater. Make me a werewolf! Make me a child-eater." Because that's fundamentally what a werewolf is. Werewolf -- "man-wolf" -- is a compound of the same type as sparrowhawk or ant lion. A werewolf is not primarily a man-like wolf or a man who turns into a wolf, but a predator that hunts man as its natural prey.

So, how do you feel about werewolves? I think we can agree that, to quote a book title from another of the Four Horsemen of New Alycanthropism, Werewolves Are Not Great. If they existed, we would have to exterminate them.

Exterminate them? But werewolves are virtually human! Legend has it that they are humans, cursed to transform, but even if that is not true, the Cheetah Principle tells us that they can't be ordinary animals. To live by hunting something as fast as a gazelle, a predator must be even faster itself -- and to hunt something as intelligent as a man? Werewolves must surely be sapient -- have souls -- be people -- so can we just exterminate them?

Yes. It is permitted to kill even a human being if he is trying to kill you -- and werewolves are, by their very nature, trying to kill us.

Even if you balked at actually killing werewolves -- and I don't think many people would -- you would surely at least agree that they ought to be encouraged to quietly go extinct. Mass sterilization might be a relatively humane option. And if even that strikes you as problematic, then if it so happened that werewolf populations were in decline anyway, we should at the very least not actively do anything to reverse that trend.

Most people aren't going to have so many qualms, though. Death to werewolves, right?

⁂

Fearful symmetry?

A common philosophical underpinning to ethical vegetarianism (particularly the Buddhist variety) is the idea that killing people is wrong because people are sentient -- capable of suffering -- and that many or most animals are sentient as well. Therefore, animals ought not to be killed unnecessarily.

But this view implies that tigers, for example, are basically the same as werewolves.

Tigers must kill to live. Their very existence brings suffering and death to other sentient beings. By vegetarian logic, it would be better if tigers did not exist. While we obviously can't kill them -- they're sentient beings, too! -- we should rejoice at the news that they are an endangered species. Instead of supporting the "save the tiger" movement, which directly causes suffering and death to wild boars and sambar deer, we should be thinking about a trap-neuter-release program.

No vegetarian I know thinks this way. In fact, I am sometimes asked how an animal lover (for such is my reputation) could fail to be a vegetarian. My answer is that most of the animals I love are predators, and that I therefore accept the validity of the predator lifestyle.

But not the werewolf lifestyle. My position is clear. Tigers have a right to exist. Werewolves -- or, for that matter, individual tigers who have become man-eaters -- do not.

We, too, are a predatory species, and we have a right to be just that. It's okay to be a predator. But not a werewolf. Vegetarians who disagree with that will have to ask why, and see if they have a coherent answer.

⁂

Preventing harm vs. preventing existence

Ours is different from most predatory species in that we have two very different modes of predation: hunting and animal husbandry. These days, of course, most of our meat comes from farms, with large-scale "hunting" (harvesting from the wild) being mostly limited to fish. The would-be vegetarian has to consider each separately, for they are very different.

Vegetarianism is usually grounded in some desire to prevent harm to animals. This prevention is indirect, though. If I am offered a pork chop and refuse to eat it, no harm is being directly prevented. The pig is already dead, and my refusal to eat its flesh won't bring it back to life. However, the consistent refusal of significant numbers of people to eat meat would reduce the economic demand for meat, which in turn would reduce production. Fewer animals would be slaughtered.

Fewer animals would be slaughtered -- and what would that mean? This is where the distinction between hunting and farming comes into play. For hunted species -- especially those, like the swordfish, that have few natural predators -- not slaughtering them generally means allowing them to live out their natural lives in peace. (For those lower on the food chain, it more likely means letting them be killed by non-human rather than human predators.) For farmed species, though, the situation is entirely different. How do you think pig farmers would react to a sharp drop in the demand for pork? By only slaughtering half of their swine and allowing the rest to live long, happy lives and die peacefully in their sleep -- or by arranging that fewer pigs be born in the first place? You're not improving the quality of porcine life, just reducing the quantity.

In fact, I think we probably need to make a four-way distinction:

- Wild animals from prey species are going to be killed by predators one way or the other, so human predation creates no new harm.

- Wild animals from non-prey species (e.g. swordfish, bears) or from species whose natural predators are extinct (deer in most places) generally won't be killed unless we kill them.

- Some farmed animals (e.g. factory-farmed chickens) probably have an existence that is worse than death, and reducing the number of such animals in existence seems a worthwhile goal.

- Many other farmed animals do not have an existence that is worse than death, and preventing their existence seems entirely uncalled-for.

⁂

Animal welfare vs. personal purity

Many vegetarians get into the movement via a concern for animal welfare, only to slip by slow degrees into the mindset that if they partake of animal flesh they will be unclean until even. Some will even treat meat as a contaminant, refusing to eat anything -- however meat-free it may be -- that was prepared with fleischig kitchenware. These people should drop the pretext that the mutant kashrut by which they live has anything to do with kindness to animals.

Friday, October 23, 2020

When 2,240-ton cats roamed the earth!

|

| Looks legit, right? |

Alexandre Saint-Yves d'Alveydre's 1884 book Mission des Juifs was finally translated into English in 2018 by Simha Seraya and Albert Haldane. They released two versions: a simple translation called Mission of the Jews and an annotated one called The Golden Thread of World History. I bought the latter, which as turned out to be a mistake. So far, I would estimate that at least 90% of the footnotes simply implore the reader to read The Urantia Book (published decades after Saint-Yves's death, and therefore textually irrelevant!), and none of them shed any useful light on the text itself. (The translation itself is also amateurish in the extreme, but it's unfortunately the only game in town.)

Among the many confusing passages the translators did not see fit to annotate at all is this one about prehistoric animals:

The mammoths, the ten-meter-tall behemoths, the five-meter-long Brazilian lion, the twenty eight meter-tall felis smilodon, the diornis bird as big as an elephant, the ornitichnithès, a still more colossal bird, judging by its strides of three meters, all those beings who have returned to the invisible are but signatures of their indestructible celestial Species, the symbols of the biological and purely intelligible Powers of the Cosmos.

"Behemoths"? Is that supposed to refer to some specific animal? And since when have there ever been lions of any description in Brazil? And, wait, did you just say a 28-meter-tall Smilodon?

Those less familiar with the metric system might not have an intuitive sense of how completely ridiculous that is, but what we're talking about here is a saber-toothed tiger as tall as a nine-story building, five times the height of a giraffe, 65% taller than Sauroposeidon proteles, the tallest known dinosaur. Sauroposeidon was so tall because of its ridiculously long neck, but a cat's height is measured at the shoulder.

Smilodon populator, the saber-toothed tiger we all know and love, was 1.4 m tall and 2.6 m long. It weighed about 280 kg, and its namesake teeth were 30 cm long. Scaling up, then, this hypothetical S. alveydreii with a height of 28 m (92 ft) would be 52 m (170 ft) long, weigh 2,240 tons (heavier than 20 blue whales), and have canine teeth 6 m (20 ft) long. Forget being taller than a giraffe; this thing would have had teeth the size of giraffes!

I finally just had to look up the original (qv):

Les mammouths, les mastodontes, de dix mètres de haut, le lion du Brésil de cinq mètres de long, le félis smilodon de vingt-huit mètres, le diornis, oiseau grand comme un éléphant, l’ornitichnithès, oiseau plus colossal encore, à en juger par ses enjambées de trois mètres, tous ces êtres rentrés dans l’Invisible ne sont que les signatures de leur Espèce céleste, indestructible, ne sont que les symboles de Puissances biologiques et purement intelligibles du Kosmos.

So the "behemoths" in the English version are mastodons. Why on earth would they change that perfectly clear word to the vague behemoths -- at the same time leaving untranslated such an opaque term as ornitichnithès?

Now, about those crazy measurements.

Were mastodons 10 meters (33 feet) tall? No, of course not. They were 10 feet tall, about the same as a modern elephant. Saint-Yves must have read something in English about mastodons and misunderstood the units being used.

The "lion du Brésil" is a tougher case, as no lions, living or fossil, have ever been discovered in that country or (probably) anywhere else in South America. (It has recently been proposed that some jaguar fossils in Patagonia actually belonged to Panthera atrox, the American lion, but nothing like that had been suggested in Saint-Yves's time, and anyway it's still not Brazil.) The Eurasian cave lion (P. spelaea) grew to five feet at the shoulder, so perhaps Sant-Yves once again read feet as meters (and, in this case, height as length), but I have no idea why he thought such an animal was from Brazil of all places. Smilodon did live in Brazil, and some of the first Smilodon fossils were found in that country, so perhaps Saint-Yves got two quite different extinct felids mixed up in his memory.

And now we come to the gargantuan Smilodon itself -- le félis smilodon de vingt-huit mètres. The text does indeed say twenty-eight meters, but "tall" was added by the translators -- so perhaps what Saint-Yves meant was that the animal was 28 meters long. This would make it a mere 1,250 times as big as a real Smilodon, rather than 8,000 times -- a considerable improvement, but obviously not enough of one! Since 2.8 meters is pretty close to the real length of S. populator, my best guess is that Saint-Yves carelessly omitted a decimal point when he was doing his research and then -- somehow! -- later wrote in his book that "le félis smilodon" was as long as a blue whale without setting off his own BS detector. And Seraya and Haldane faithfully translated it, guessed that the big cat was most likely 28 meters tall rather than long, and proceeded as if that were a perfectly normal thing to write, with no need for an explanatory note. I guess The Urantia Book didn't have anything to say about it.

As for the other two creatures mentioned, le diornis should be Dinornis, the giant moa of New Zealand. It was in a general sense "as big as an elephant" -- a bit taller than an elephant but only one-tenth as heavy. Ornitichnithès should be Ornithichnithes -- a name formerly applied to some tetrapod footprints dating to the Carboniferous, and so obviously not those of a bird! Current opinion is that they were made by a mammal-like reptile of some sort. (The translators have Google, too. Why couldn't they have done this work for me?)

⁂

Really, though, who cares if a book about the mission of the Jews gets its paleontology wrong? It's not a science book, right? Well, I think we need to guard against the Gell-Mann Amnesia effect. An author who can get so many facts in a single paragraph so wrong -- so insanely wrong! -- who can swallow the idea of a 28-meter tiger without batting an eye -- is likely to prove equally careless and gullible when it comes to things that can't be so easily checked.

Saturday, August 1, 2020

The meaning of birds

You cannot underestimate how far people are trapped in modernity. I once watched a nationalist pagan Youtuber who, while talking about population genetics on his computer, noted that an owl had landed on a branch outside his window the night before. For an ancient pagan this would have been an event of enormous import, the only thing worth talking about; the birds were messengers from the gods and augury was central to paganism. But the Youtuber, despite identifying as anti-modern and totally primal, rejecting even Christianity as too modern, mentioned the owl in passing--as if it were a curious and mildly interesting fact. The population genetics on his screen were much more important and real to him, and so he spurned a divine messenger.Even people who have taken a conscious step out of modernity are still consumed by its frame of reference; when they see a bird, they don't see a sign--just a wildlife fact.

Friday, July 24, 2020

Eight lyouns and an hundred egles

In þat contré ben many griffounes, more plentee þan in ony other contree. Sum men seyn þat þei han the body vpward as an egle, and benethe as a lyoun: and treuly þei seyn soth þat þei ben of þat schapp. But o griffoun hath the body more gret, and is more strong, þanne eight lyouns, of suche lyouns as ben o this half; and more gret and strongere þan an hundred egles, suche as we han amonges vs.

Friday, June 19, 2020

Wednesday, May 27, 2020

Cats and lilies

Fortunately I did not have to learn this from tragic experience, though it was rather a near escape. I noticed that the cats seemed abnormally interested in a vase of flowers my wife had just put in the kitchen, and thankfully I followed up the hunch, googled "cats and lilies," and very likely saved a feline life or two. The lilies are now locked away in a room the cats do not have access to, and we will not be bringing any representatives of that particular genus into the house again.

I mention this primarily to spread the word to any fellow cat owners who may be unaware of this potential threat, but also to note the strange appropriateness of it all from a symbolic point of view.

Lilies, besides being a traditional funeral flower (which therefore ought to be deadly to something), are also an age-old symbol of purity, and especially of sexual purity or virginity. They are a common motif in paintings of the annunciation.

|

| Auguste Pichon, The Annunciation |

The cat, on the other hand, is a traditional symbol of infidelity -- partly, I think, due to the habit of thinking of cats as the "opposite" of dogs, the latter being a byword for loyalty -- and of sexual misconduct. A cathouse is a whorehouse, and a womanizer is said to have "the morals of an alley cat."

|

| David Hockney, Mr and Mrs Clark and Percy |

This weird appropriateness is underscored by the fact that, in defiance of all botanical common sense, the daylily (which certainly counts as a lily as far as symbolism is concerned) insists on being toxic to cats in precisely the same way that true lilies are, despite being more closely related to onions and asparagus than to lilies proper.

Sunday, May 3, 2020

Each continent and region has its own biological "style"

|

| American and European badgers |

|

| American and European robins |

|

| American and European red squirrels |

This is just a gestalt impression that I can't begin to quantify or explain, so I'm hoping I'm not the only one who sees it -- but, doesn't there seem to be a common "style" underlying the three American species (on the left), and another, quite different style manifested in the European ones (on the right)? It's as if two artists with very different souls had each been commissioned to paint a badger, a robin, and a red squirrel. Seeing the "Americanness" of the one set and the "Europeanness" of the other is as easy -- and as hard to explain -- as distinguishing a Titian from a Rembrandt.

(I remember once looking at a brochure from a local museum, advertising a Chagall exhibition. Of the pictures featured in the brochure, one immediately stood out as vastly superior to the others and made me think that maybe Chagall wasn't as crappy an artist as I had always thought. It turned out to be a Picasso.)

Something similar can be said for the "Africanness" of African animals, the "Asianness" of Asian ones, and so on. On a smaller geographic scale, I am continually amazed at how consistently Japanese birds look Japanese; observing a new-to-me bird in Taiwan, I can almost always accurately guess whether or not it is also found in Japan.

Although comparisons, like the American-European ones above, make regional styles easier to see, they can also be recognized without comparison. My first sense that there was something ineffably American about American animals came from looking at a picture similar to this one.

Just as Rembrandt and Titian, and even Picasso and Chagall, are all part of a larger style called "European art," which is quite distinct from, say, Chinese art -- so I sometimes feel that I can sense a common "Earth" style underlying all the animals in the world, even though I obviously have no other set of animals to compare them too. The planetary spirit of Earth may be harder to see, for lack of contrast, than the regional spirits of various countries and continents, but it is no less real.

Tuesday, April 7, 2020

Every cat has a right to eat fish

I had just finished having lunch with my wife. She had had a salad with shrimps in it but had given at least half of the shrimps to the very insistent Geronimo, one of our cats, who likes shrimp better than anything else in this world. This led me to comment on how strange it is that cats should have such a strong preference for seafood given that they can't swim, hate water, and would presumably never eat seafood in the wild. It's not just fish but shrimp, squid, oysters -- almost any kind of seafood, really -- and even among fish they have a strong preference for large marine species such as tuna.

After lunch I opened up a book I had just started, Jonathan Cott's biography of Dorothy Eady, alias Omm Sety, a 20th-century Englishwoman most notable for her firm belief that she was the reincarnation of an ancient Egyptian priestess. Wanting to have a mental picture of this character as I read, I flipped forward to the plates and found this.

The caption (also notable for its curiously "broken" English) mentions the clay figurines just barely visible in the background but has nothing to say about the feature that dominates the scene: an enormous poster of a cat reading "Every cat has a right to eat fish."

Why should such a poster exist? It seemed as if it could only be an advertisement for a particular brand of cat food, but no brand name was visible. Googling the slogan yielded, amazingly, only one hit (this post will bring the total up to two), but that did lead me to a vintage cat food advertisement (UK, 1979, just a year before the Eady photo was taken).

This is obviously an ad from the same series as the one that appears in the Eady photo, differing in that it features a different cat and, more importantly, that it has the expected brand name written at the bottom in huge letters.

One can only conclude that Eady, a fondness for cats perhaps being part of her "ancient Egyptian" shtick, got a Choosy cat food advertisement, cut off the part with the brand name, and put it up on her wall -- but left the slogan intact because there was no way to remove it without also cutting the cat's ears out of the picture. This strikes me as rather eccentric even by reincarnated-priestess-of-Isis standards. It's not as if pictures of cats -- even Egyptian-looking ones! -- are so hard to come by that anyone should have to resort to incompletely mutilated cat food ads.

Note also that one can buy an ad like this on eBay now because it's a vintage ad of the sort some people like to collect -- but it wasn't "vintage" in 1980 and would not have been for sale to the general public. It's the sort of poster that would have been displayed on the wall of a pet shop, veterinary clinic, or some place of that sort, and Eady must have specially requested it from the owner of some such establishment so that she could take it home, cut off the bit with the logo, and put it up on her wall!

Friday, March 20, 2020

Black dogs and Reubens

Among those present was the first dog I ever owned as a child in America, a black Lab-Pointer mix whose name had been determined for her by the white zigzag mark running down her chest. She was dancing all around, wagging her entire body in a transport of delight, and my first thought was to find my cell phone and call my wife. "Wait till she hears that Lightning has come back!" (In the real world, of course, my wife never knew Lightning, who died many years before we met.)

Later my wife was there, too, standing with me in front of the house, and I pointed out to her the one dog I didn't recognize, a curly-haired female something like a Labradoodle. "That's Fournier!" she said. "That's the new dog!" -- and though that means nothing to me in real life, in the dream I accepted it as a sufficient explanation.

"Shall we bring them all into the house?" I said. "But I'm afraid they'll poop."

Later I dreamt that I saw several variations on the same Internet meme:

|

| Something like this |

Later still I was at a very large house party where everyone was milling about. I saw somebody eating a sandwich and suddenly decided that I wanted a Reuben -- corned beef, Swiss cheese, sauerkraut, and Russian dressing on rye -- but didn't know where to find one or even the ingredients to make one. I wanted to ask someone at the party, but I didn't really know anyone.

Then finally I saw someone I knew -- one of my old linguistics professors from my college days, a Dr. Levine. I was about to walk up to him and ask if he knew a kosher-style deli in the area, but then I suddenly got cold feet. "He's going to think I'm asking him because he's Jewish," I thought, "not because he's the only person I know. And a Reuben's not even kosher anyway; it's like asking a Chinese guy where I can buy fortune cookies." So I just gave him a nod and a smile and walked away.

Then I suddenly thought, "Wait. I have a big nose. I have an Eastern European name. He probably assumes I'm Jewish. It won't be offensive at all!" But it was too late; he had disappeared into the crowd.

Monday, March 2, 2020

Not just fear; dogs can smell leonine thoughts

|

| Blue bipedal lions with Mesopotamian beards: Dogs don't like them |

Anyone who, like me, makes a habit of rambling through the neighborhood somewhere around one-thirty or two a.m. in the morning, when only the goblins are out, has to deal with the occasional overly aggressive dog.

For a long time, my go-to technique for scaring off dogs was the old standby of stooping down as if I were going to pick up a stone, but a year or so ago I inadvertently discovered another method. I was writing about the World card of the Tarot at that time, which involved much brooding over the Four Living Creatures, one of which is the lion. Several pye-dogs were out and about, minding their own business. As I was walking along, I suddenly visualized myself as a lion -- specifically, as the bipedal lion depicted on the cover of the Rolling Stones album Bridges to Babylon -- and the instant I did so, all the dogs stopped, looked at me, and then turned tail and ran!

A few nights later, I was out walking again, and a big black dog came running at me full speed, teeth bared and snarling, so I tried it again. I just kept walking as before but imagined myself as a lion. Again, the reaction was instantaneous. The dog fairly skidded to a stop, scrambled a bit, and then took off whimpering back the way he had come. Since then, I've used this technique every time a dog comes looking for trouble, and it works every single time. (On dogs only. Cats and herons are unaffected.)

How does it work? I suppose that the visualization must cause some tiny, unconscious changes in my body language, and that the dogs pick up on that -- but that doesn't explain why, the first time, I somehow got the attention even of dogs that hadn't been looking at me before. Perhaps, as the headline suggests, they do literally smell our states of mind, via changes in hormones and sweat and such -- or perhaps it's something more mysterious. In any case, I offer it as a possible tool for anyone who sometimes finds it necessary to strike fear into canine hearts.

Tuesday, February 25, 2020

Cat bitten by radioactive spider

This is Geronimo, one of my home's nine or ten resident felines. I haven't the slightest clue how he managed to get up on top of this tchotchke cabinet, which is a sheer vertical face with no protruding shelves or anything to use as stepping stones. I think he forgot how he did it, too, since I had to use a stepladder to get him back down.

Monday, February 17, 2020

What species was Bitter Green?

Is the title character in the Gordon Lightfoot song "Bitter Green" (1968) a dog, a horse, or a woman?

Upon the bitter green she walked the hills above the townThis certainly sounds like a horse. A grazing animal would naturally spend its time "upon the . . . green," and only the footsteps of a large hoofed animal would echo through the hills. A woman's footsteps might echo on pavement, but not on a green. It's hard to know what to make of the last phrase, since "footsteps as soft as eiderdown" surely means silent footsteps, the kind that don't echo. Anyway, on balance these lines support the horse theory.

Echo to her footsteps as soft as eider down

Waiting for her master to kiss away her tears"Master" normally refers to the human owner of a domestic animal, but it might be used poetically of a woman's husband or lover. Tears of sorrow, on the other hand, are shed only by human beings, but again could be ascribed poetically to other species. Waiting through the years for one's master to return is a behavior most stereotypically associated with dogs, but horses and women have also been known to do it.

Waiting through the years

Bitter Green they called her"Loving everyone that she met" sounds like an animal, and specifically like a dog. Applied to a woman, the phrase is rather scandalous and also seems inconsistent with the idea of a Penelope patiently waiting for her true love to return. "Bitter Green" itself also seems like a name that would be more naturally given to an animal than to a person. A woman would be known by that rather strange nickname only if no one knew who she was or what her real name was, which is inconsistent with "loving everyone that she met."

Walking in the sun

Loving everyone that she met

Bitter Green they called herThis also sounds like an animal. A woman whose husband or lover had disappeared would still have a home and would naturally wait there (perhaps by the window, wearing a face that she keeps in a jar by the door) rather than in the sun.

Waiting in the sun

Waiting for someone to take her home

Some say he was a sailor who died away at seaHorses don't kiss people, but dogs and women do.

Some say he was a prisoner who never was set free

Lost upon the ocean he died there in the mist

Dreaming of her kiss

But now the bitter green is gone, the hills have turned to rustIs this just a seasonal change? But Bitter Green waited "through the years."

There comes a weary stranger, his tears fall in the dustThis strongly supports the woman theory. The most natural interpretation is that the long-awaited "master" finally returns, but too late, and kneels in tears at Bitter Green's grave. It seems unlikely that a dog or horse would have been buried in a churchyard, especially in her owner's absence. (Against this, note that this line is "dreaming of a kiss" -- not "her kiss" as in the chorus. Perhaps the wife whose grave the stranger is visiting is distinct from Bitter Green.)

Kneeling by the churchyard in the autumn mist

Dreaming of a kiss

In one of the sci-fi stories I wrote as a very young child, the astronaut protagonist had, among other items of spacefaring equipment, a "space shovel" which he used for digging on the surface of distant planets. I had no very clear idea of how a space shovel might differ from a common-or-garden shovel, but the phrase "space shovel" just sounded right, and it seemed that an astronaut ought to have one. It was not until years later that it dawned on me that "space shovel" sounded an awful lot like the then-common phrase "space shuttle," and that it was almost certainly this unconscious echo that made me think the former phrase "sounded right." I think some similar unconscious association was likely behind Gordon Lightfoot's choice of the phrase "Bitter Green."

Friday, August 9, 2019

Naming the animals

People always seem to assume that when Adam named the animals he was creating a language, assigning common nouns to the various species -- saying, "You lot shall be called dogs; you lot, cane spiders; you over there, white-throated guenons," and so on.

Obviously he was doing nothing of the sort. If Adam had been tasked with inventing a language from scratch, nouns for animals would have been a relatively low priority. Why wasn't he coining words like leg, tree, breakfast, sun, or gully? Why did he name only animals -- and, later, his wife? Because he was giving them names -- personal names.

I've always followed Adam's example in this. Any animal that I see often enough to recognize sooner or later gets a name, and I've always had a knack for noticing the features that distinguish each individual animal from its conspecifics. There are limits, of course -- I never could tell one black-capped chickadee from another -- but I clearly remember that as a child I distinguished and named each of the dozen or so mourning doves that frequented our bird feeder. Individual ants of course did not receive names, but colonies did. Certain colonies enjoyed our favor and received occasional gifts -- the biggest of which was a roadkilled toad which the workers assiduously remodeled their whole hill to accommodate.

*

I've often been surprised at how readily animals of a variety of "higher" species seem to grasp the concept of a name -- something that seems pretty abstract for an animal to deal with. Dogs and cats, of course, but also, surprisingly, sugar gliders -- very small animals with no real history of domestication.

Each of our cats is known by several different monikers in two different languages, but each can recognize and respond to all of its names. The cat called Pinto, for example, answers to Pinto, P, Doudou, Heibai, and Xiaohuai. He also understands that Scipio is the name of another cat whom he particularly hates, and he responds to that name by lowering his ears and tensing up. I find this ability -- in a not-very-social species that communicates primarily by body language -- nothing short of astonishing. I've sometimes wondered if it might not have a psychic component -- if the cat responds not so much to the name itself as to the attention channeled by the act of uttering it.

Thursday, August 8, 2019

A frog among herons

I stepped out last night and found a frog perched on the back windshield of my car -- a rather handsome medium-sized brown frog with dark eyes. I'm not really up on the frog species on Taiwan yet, but if I had seen it in America I would have called it a Little Grass Frog, and I assume it was something along those lines -- a "tree frog" but of a non-arboreal species.

I always feel responsible for animals that show up at my doorstep, and clearly this frog had to be moved. He had unwittingly wandered into the territory of a half-dozen feral cats that pretty much kill anything that moves (they just got a skink the other day), and one of them particularly likes to sleep on that car.

I first tried to move it by hand, with the predictable result. (As Hobbes observed, "They drink water all day just in case someone picks them up.") This spooked the frog enough that it hopped away and climbed up into the innards of the neighbor's motorcycle to hide. I spent some time with a flashlight trying to locate and extract the creature, but it had hidden too well. In the end, I had to give up and just hope that it had the good sense to come out before morning.

An hour or so later, I stepped out again, and the frog was back on the car! This time I managed to persuade it to hop into a little paper bowl, and I set off to find a safe place to let it go. The frog settled in, folding its limbs up as neatly as a bat's, and waited patiently in the bottom of the bowl, turning its head occasionally to check on me but otherwise motionless. (In fact, his movements and general mien reminded me very much of one particular bat I had known years ago, so much so that thoughts of reincarnation fluttered around the periphery of my attention. With short-lived species, who can say how many times, and in how many guises, the same handful of beast-souls might keep crossing one's path?)

My wife had suggested that I let him go on the big magnolia by the side of the road, but in the end I decided that the dangers of the road, and the lack of water and of other vegetation, outweighed the commonsense consideration that a tree frog ought to be in a tree. (Anyway, my somewhat biologically informed hunch was that this, while technically a tree frog in the same way that a panda is technically a carnivore, was a mostly non-arboreal creature I was dealing with.) I opted instead for a paddy field with a few small trees in it, some distance from the road.

When I reached the intended release point, I was greeted by the sound of heavy wingbeats, and a large heron rose up from a nearby canal and flapped off into the night. Herons, of course, eat frogs, and I almost decided to take my little charge elsewhere. However, I already knew from experience that there were no unheroned precincts in the vicinity, and in fact for the moment this was the one stretch of paddy where I knew for sure there was not a heron hunting -- so I said a brief prayer for him and let him go, comforting myself with the thought that, whatever the risks, he was at least safer now than he would have been if I had left him in the lions' den where I had found him. "Go your way: behold, I send you forth as a frog among herons." In the end, I'm afraid, safety just isn't on the menu for frogs. They must seek other satisfactions. He made a few trial hops, turned back to look at me for a second, and then disappeared into the vegetation.

*

The strange thing is that I'm usually on quite friendly terms with the local herons and have no objections to their catching and eating frogs -- but I wanted very much for them not to eat this particular one. But why? Why should this frog live and others die? Just because it's the one I happened to find -- or rather, the one that happened to find me? Well, yes, that's the reason -- and on some level I feel quite sure that such thinking isn't as irrational as it seems.

Ace of Hearts

On the A page of Animalia , an Ace of Hearts is near a picture of a running man whom I interpreted as a reference to Arnold Schwarzenegger....

-

Following up on the idea that the pecked are no longer alone in their bodies , reader Ben Pratt has brought to my attention these remarks by...

-

1. The traditional Marseille layout Tarot de Marseille decks stick very closely to the following layout for the Bateleur's table. Based ...

-

Disclaimer: My terms are borrowed (by way of Terry Boardman and Bruce Charlton) from Rudolf Steiner, but I cannot claim to be using them in ...