To this day there are 'artists' in the East who make a business of carving genuine roots of mandrakes in human form and putting them on the market, where they are purchased for the sake of the marvellous properties which popular superstition attributes to them. . . . The virtues ascribed to these figures are not always the same. Some act as infallible love-charms, others make the wearer invulnerable or invisible ; but almost all have this in common that they reveal treasures hidden under the earth, and that they can relieve their owner of chronic illness by absorbing it into themselves.

Tam multa, ut puta genera linguarum sunt in hoc mundo: et nihil sine voce est.

Tuesday, November 15, 2022

Mandrakes, treasure-hunting, syzygy

Thursday, June 16, 2022

Minor sync: Roosh Valizadeh's birthday

Yesterday, June 14, I was browsing Synlogos and noticed a link to a post by Roosh Valizadeh -- "13 Tips for Reading Books" or something. I didn't read the post, but for some reason seeing it made me think, "Hey, I wonder how old Roosh is." I don't know why that came to mind. I don't know exactly how old most bloggers I read are, and I've never felt the need to find out. But in this case I just suddenly wanted to know, so I looked it up.

He was born on June 14, 1979 -- so it was on his birthday that I had this sudden urge to look up his date of birth.

Possibly this was something I already subconsciously knew. His "About Roosh" page, which I think I must have read before (I recognize the photo with the striped shirt and the little black dog) says "My birthday is on Flag Day, a national holiday, which I share with Donald Trump." I definitely know Trump's birthday, and that it is Flag Day (and also my sister Kat's birthday), since I've mentioned that fact several times on The Magician's Table, so that should have served to make Roosh's birthday particularly memorable. Perhaps when I happened to see his name on June 14, I was nudged by a not-quite-conscious memory, and that is what made me wonder about his age.

Today, when I wanted to write a post noting this sync or crypto-memory or whatever, I found that I couldn't remember who it was whose June 14 birthday I looked up on June 14. My first thought was that it had been Amber Heard, of all people! I spent quite some time scrolling in vain through lists of famous people born on June 14 before I suddenly remembered.

Appropriately, given these memory lapses, June 14 also turns out to be the birthday of Alois Alzheimer.

Saturday, June 15, 2019

An odd case of the Madeleine Effect

One would assume that each such experience is a one-off. One would assume that if Proust had taken up the habit of eating tea-soaked madeleines every day, he would not have experienced daily clockwork revelations of le temps perdu. One would assume that only a relatively uncommon stimulus would have the power to call to mind a specific previous instance of the same.

"One would assume," I say -- would, were it not for direct experience to the contrary.

*

The relatives at whose home I saw the movie live fairly close to our own house, but we don't visit them that often. However, I pass through that general area several times a month, and every time I get within a half-mile or so of their home -- the area in which I had walked after seeing 47 Ronin -- it triggers an memory of impressive (if perhaps not quite Proustian) vividness. I remember walking along the road, passing a rather handsome stray Formosan mountain dog, seeing a white sedan drive past me and then turn left. I remember a long row of Roman-style banners which had been put out to advertise for an election (and which have long since been taken down), and how their fluttering in the dark struck me as somehow uncanny. And I remember what I was thinking at the time -- mostly about the many-eyed beast, of course, and the dream which had anticipated it.

*

What would cause this sort of recurring Madeleine Effect? My guess is that it has to do with the fact that, while the stimulus is one I encounter often, it is never accompanied by any other memorable events which might compete with the original. When I visit those relatives, actually being in the house where I saw the movie does not trigger any vivid memories -- probably because all kinds of different things have happened in that house, of which watching 47 Ronin is just one. The house is not haunted by a single dominating memory. On the roads near their house, though, nothing ever happens. I just pass through. I've only been walking there that one time, which was memorable because of the uncanny experience I had just had, and which imparted its uncanniness to the otherwise unremarkable scenery. The first time I passed through after that, I experienced an unusually vivid memory -- which was itself a memorable experience, and thus reinforced the memory of the original walk. Aside from my walk, and my vivid memories of that walk, nothing at all memorable has ever happened to me in that area, so no real new memories are formed to swamp out the original one.

Monday, May 6, 2019

Changing the future and changing the past

*

The first matter of business is to establish exactly what is meant by change. As a simple example of a change, consider my marital status, which changed in the latter part of 2010. Prior to that date, I was not married; after that date, I was and am. That's what change means: that a given proposition ("William James Tychonievich is married") is/was/will be true at some points in time and false at others.

We can represent this change graphically by means of a colored line. The dimension represented by the line is "time," with the past to the left and the future to the right, and the color of any given point on the line represents my marital status at that point in time (blue for single, gold for married). Below is a portion of such a timeline, covering the years from 2009 to 2020.

|

| Fig. 1 |

We want to consider the idea of changing the future and the past, so this timeline is inadequate, giving no indication of which points on the line are past and which are future. We need to add something to indicate that the present moment is -- well, of course it's a moving target, changing even as I type this sentence, but this is a pretty low-resolution timeline, so "about a third of the way through 2019" will be good enough for our purposes. (If you should happen to be reading this post at a significantly later date, please be so good as to proceed on the counterfactual-to-you assumption that the present moment is indeed in that general vicinity.) Let us modify our timeline by reserving the bright colors used in Fig. 1 for past points in time and representing future points by paler versions of the same colors, like so:

|

| Fig. 2 |

There are now two points on the timeline where the color changes. The point where it changes from blue to gold represents the event of my marriage. To the left of that point, I was single; to the right, I was, am, and will be married. The point where the line changes from bright to pale represents the present moment. Everything to the left of that point is past, and everything to the right of it is future.

Now, we have already established that my marriage in 2010 constitutes an example of a change, and our timeline above locates that change to the left of the present moment -- that is, in the past. Is this, then, what we mean by "changing the past? Obviously not -- but why not, and what do we mean?

Well, the natural answer is something like this: The change in question occurred in 2010 -- which means that at that time, 2010 was not in the past but was the present year. If what happened in 2010 were to change now, that would be what we mean by "changing the past." But this introduces a distinction between 2010-in-2010 and 2010-now which cannot be represented on a one-dimensional timeline. Such time designations require two coordinates -- (2010, 2010), (2010, 2019) -- which means our simple timeline must be expanded into a two-dimensional "timeplane" of the type pioneered by J. W. Dunne and discussed in my post "The present now will later be past."

The title of that post, taken from the Bob Dylan Song "The Times They Are a-Changin'," was chosen because, while it seems very obviously true, it implicitly assumes a two-dimensional model of time. A simple timeline, like Fig. 2 above, can represent past, present, and future, but not the idea that "the present now will later be past." The very phrase "will later be past" describes the same state of affairs as being future in one sense and past in another -- which requires a rectangular coordinate system comprising two perpendicular timelines.

|

| Fig. 3 |

Now I know from experience -- my own included -- that this is point at which readers' eyes start to glaze over, but I'm afraid there's just no avoiding these diagrams. I can only ask for the reader's patience and do my best to explain. The color of each point on the timeplane in Fig. 3 represents a proposition regarding my marital status: The hue represents the content of the proposition (blue for single, gold for married), and the tint represents its tense (pure colors for past, light colors for future). Each point is located in two different temporal dimensions: The x-axis ("object time") represents the time the proposition refers to, and the y-axis ("meta-time") represent the time at which the proposition is true.

I've marked two (arbitrarily selected) regions on the plane "A" and "B," respectively, in order to use them as examples. They represent the following meta-propositions:

A: In 2010, the proposition "WJT will be married in 2012" was true.

B: In 2014, the proposition "WJT was married in 2012" was true.For completeness, we really ought to indicate the tense of the meta-proposition as well. Fig. 4, below, is so modified as to express this. Solid colors (such as were used in Fig. 3) represent meta-past, and stippling represents meta-future.

|

| Fig. 4 |

The region marked "C" in Fig. 4 represents the following meta-proposition:

In 2020, the proposition "WJT was married in 2011" will be true.The "was" in the object proposition is indicated by the use of a pure color as opposed to a tint, and the "will be" of the meta-proposition is indicated by stippling.

The red dot in Fig. 4 marks the place where the true present may be found. (Or at least, this was true when I wrote it, about a third of the way through the year 2019.) When we say, "2019 is the present year," the word "present" corresponds to the diagonal line separating pure colors from tints, and the present-tense verb "is" corresponds to the horizontal line separating solid colors from stippling. The intersection of those two lines, marked with the red dot, is "the present now." Dylan's statement that "the present now will later be past" means that if we start at the red dot ("the present now") and move vertically down into the stippled region ("will later be"), we find a pure color ("past") rather than a tint.

Take a minute to digest that. I want to be sure the meaning of these timeplane diagrams is clear before proceeding.

Now look back at the region marked "A" in Fig. 3 and the meta-proposition to which it corresponds: "In 2010, the proposition 'WJT will be married in 2012' was [already] true." And consider this: If I were to extend my timeplane diagram to cover a wider range of past times, there would be a region on that diagram corresponding to the meta-proposition "In 4000 BC, the proposition 'WJT will be married in 2012' was already true." This is fatalism, of the unassailable variety spelled out by Richard Taylor (whose argument I discuss here) -- unassailable because it does not depend on the doctrine of causal determinism. From the mere assumption that all possible statements about the future are (already) either true or false, and that their truth-value cannot change, it follows that all is fated, that whatever happens is inevitable.

To escape Taylorian fatalism, it is necessary to believe that we can change the future -- an idea which is common enough in naive discourse, and which our two-dimensional timeplane allows us to model. Let us modify our diagram, then. Instead of assuming (as Fig. 4 does) that my getting married in late 2010 is something that was always going to happen, something that was already written in the book of fate hundreds of years before my birth, or as far back as you care to imagine -- instead of assuming that, let's assume instead that I wasn't going to get married on that date, not until I actually made the decision to do so. Let's assume that my decision, rather than being just another step in the inevitable unfolding of fate, actually decided something, literally changed the future. And let's further assume (as seems reasonable) that this future-altering decision was made some months before the actual event of the marriage.

|

| Fig. 5 |

The black dot on the timeplane in Fig. 5 represents the moment I exercised my agency and made the fateful decision (which, I need hardly mention, is entirely different from a fated decision, the latter being a contradiction in terms and no decision at all).

The diagonal line that passes through the black and red dots, and divides the pure colors on the left from the tints on the right, represents the timeline of my life as I experience it, as a succession of object-time "presents." The horizontal line that passes through the red dot, and divides the solid colors from the stippling, represents the meta-time present. (The object-time present is a point; the meta-time present is a line.) The intersection of these two lines divides the plane into four quadrants, representing (clockwise from the upper left), what had happened (solid pure colors), what was going to happen (solid tints), what will be going to happen (stippled tints), and what will have happened (stippled pure colors).

*

The diagonal line -- my life as I experience it -- is exactly the same in Fig. 4 (where the future is fated) and in Fig. 5 (where it can change). It would appear, then, that there can be no empirical evidence for the one model or the other, no possible experience that would be more consistent with the one than with the other. Choosing one over the other would be a metaphysical assumption, not a conclusion from evidence.

However, that may not be entirely true. There is considerable evidence (see J. W. Dunne's Experiment with Time for starters) that, while the attention is generally confined to the point-present represented by the red dot, it can sometimes extend to other regions of the linear meta-time present, especially during dreams or similar states of relaxed or diffuse attention. In such states, we have access to the object-time future (precognition) and past (retrocognition) -- at least as they exist at the meta-time present. Under Taylorian fatalism (as diagrammed in Fig. 4), the content of object time does not vary across meta-time; the only meta-time change is that of tense (as the future becomes the past), so whatever future events are perceived through genuine Dunnean precognition will infallibly come to pass when the future times in question become present. There would be no possibility of seeing the future and then changing your behavior as a result of what you see, with the result that the foreseen event is averted. This is precisely what fatalism -- of the sort seen in the Greek myths, for example -- means. Cassandra's prophetic warnings are ignored and have no power to prevent the events they foretell. The prophecies regarding Oedipus are not ignored, but the very attempt to thwart them leads to their fulfillment. Either way, fate ineluctably plays out.

In the model where the future can be changed (as diagrammed in Fig. 5), even true precognitions need not necessarily come true. For example, look back at Fig. 5 and imagine that in 2009 (in both object time and meta-time -- that is, at a point on the diagonal line) I had a precognitive vision of 2011. Since such a vision would be of object-time 2011 at meta-time 2009, I would see myself as still single at that date. However, by the time object-time 2011 becomes the meta-time present, it will already have changed, so that the 2011 I experience will be different from the 2011 I foresaw. Nonetheless, what I foresaw was true. (If that seems like a contradiction, consider this analogy. I turn on the TV to the weather channel and discover that it is sunny in Taipei. I then get in my car, drive to Taipei, and upon my arrival find that it is raining. But what I saw on TV was true.) Instances of true precognition that do not come true would be evidence that the future can be changed.

The problem, of course, is that, if a vision or premonition does not come true, there would seem to be no grounds for considering it genuinely precognitive. For example, once in my late teens, at a time when I had no plans to go overseas, I had a very vivid and detailed dream in which I was about 30 and living in Vietnam. I'm 40 now and have never set foot in that particular country. It's possible that my Vietnam dream was genuinely precognitive, revealing what was (at that time) going to happen in the future, but that the future it foretold has since changed because of choices I or others have made. It could also be considered a garbled precognition of what in fact came to pass. (I do live in Asia and have for most of my adult life.) But there's no good reason to believe that, and the simplest explanation is that it was just a dream and not precognitive at all. Certainly such a dream cannot constitute evidence that the future can be changed. Is such evidence possible?

Consider the premise of the Final Destination series of horror movies. The protagonist has a sudden vision of a series of events leading up to all his friends dying horribly in a freak accident. When the foreseen events begin to play out in real life, he panics and manages to prevent his friends from getting on the doomed plane or roller coaster or whatever. Then the freak accident occurs as foreseen, except that his friends are not among those killed by it. Later they all go on to die horribly anyway, in different freak accidents, because "you can't cheat death," but that's not germane to my point here, which is that the originally premonition is clearly a true one even though it does not come to pass exactly as foreseen. When people act on a precognitive warning so that the foreseen event does not happen, but subsequent events make it abundantly clear that it would have happened had they not taken action, that is evidence that the future can be changed.

Such evidence in fact exists. The literature on precognition is full of Final Destination type stories (minus the post-accident bit where everyone dies horribly anyway). Someone has a premonition of being in a plane crash, they cancel their tickets, and then the flight they would have been on crashes. That kind of thing.

*

What about changing the past? Well, it's a bizarre idea, so our illustrative example will be a little bizarre as well. I must ask the reader to suspend disbelief, ignoring for the moment the question of whether or not such things can really happen. Our question is what it would mean for the past to change, and, supposing it did change, whether there could be any empirical evidence of that change.

Suppose that "originally" I chose not to get married in 2010. Years later, in 2015, I looked back on that choice with regret and said to myself, "I wish I'd married that girl when I had the chance!" A passing genie happened to hear my remark and granted the wish. From that moment, it suddenly became true that I had gotten married in 2010. We can represent this hypothetical story graphically as below, in Fig. 6.

|

| Fig. 6 |

Remember that the diagonal line dividing the pure colors from the tints represents my life as I actually experience it, as a succession of presents -- and notice that in the world depicted by Fig. 6, I never actually experience my own wedding or the first several years of my married life. I go directly from being a bachelor to having been married for nearly five years! Surely such an obvious discontinuity in my experience could not possibly go unnoticed, and surely the fact that people's lives don't include such discontinuities is evidence that the past cannot change -- right?

Well, not exactly. Remember that causation is an object-time phenomenon. When object-time 2010 changed in meta-time 2015, all subsequent points in object time also changed as a result of the causal effects of that 2010 wedding. For example, if photos were taken at the wedding, those photos will (after the granting of my wish) still be there in 2015 and after. But if the creation of photos is one of the effects of the wedding, the creation of memories in the minds of the participants is another. If my memories of the past are understood to be effects of those past events in the ordinary sense of that word (i.e., one of the effects of a given past event is an alteration in the state of my brain, which alteration persists through time and constitutes my memory of that event), then my memories at any given point in my life will be of what preceded that point horizontally (i.e., in object time), not diagonally along the line of my actual experience. If the past cannot be changed, the difference is immaterial, since the content of the horizontal and diagonal pasts will be identical. If it can be changed, then as soon as the change has happened, the content of my "original" past is inaccessible to me. When, at the moment marked with the black dot, I suddenly transform from a bachelor into someone who has been married for five years, my memories change as well. I would have no memory of ever having chosen not to get married in 2010, nor of regretting my choice and having my wish granted by a genie. My memory would tell me that I had "always" gotten married in 2010, and all observable effects in the present would also be consistent with that. No evidence that the past had changed would be possible.

What about retrocognition -- "paranormal" direct access to the past, corresponding to precognition and different from ordinary memory? Would that give us access to the "original" past, before it had changed? No, because like precognition, it represents an expansion of attention from the point-present to the linear present of meta-time (represented in the figures by the horizontal line passing through the red dot).

*

I had originally planned to discuss the so-called "Mandela Effect" -- the phenomenon of memories that don't match documented history (such as many people's memories of Nelson Mandela having died in prison, or of the Berenstain bears being called the Berenstein Bears) -- as possibly representing memories of the past before it was changed, but our two-dimensional time model has no way of accounting for such "memories" (except to say that they are simply errors). That will require us to venture into the even-more-confusing domain of meta-meta-time -- and, this post already being quite long enough, I think I will reserve that discussion (and a discussion of the moral significance of changeable vs. unchangeable pasts, as raised by Bruce Charlton) for the sequel.

Ace of Hearts

On the A page of Animalia , an Ace of Hearts is near a picture of a running man whom I interpreted as a reference to Arnold Schwarzenegger....

-

Following up on the idea that the pecked are no longer alone in their bodies , reader Ben Pratt has brought to my attention these remarks by...

-

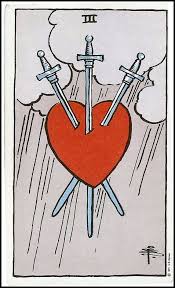

1. The traditional Marseille layout Tarot de Marseille decks stick very closely to the following layout for the Bateleur's table. Based ...

-

Disclaimer: My terms are borrowed (by way of Terry Boardman and Bruce Charlton) from Rudolf Steiner, but I cannot claim to be using them in ...