While Éliphas Lévi did not create a Tarot deck, His influence on the Rider-Waite version of the Wheel of Fortune card is so substantial that he deserves a post of his own.

In Dogme et Rituel de la Haute Magie (published 1854-56, translated by Waite in 1896 under the title Transcendental Magic), Lévi makes the connection between the words tarot and rota (Latin for "wheel," as in rota fortunae) and associates them with the Tetragrammaton:

The incommunicable axiom [on which the Great Magical Arcanum depends] is enclosed kabalistically in the four letters of the Tetragram, arranged in the following manner: In the letters of the words AZOTH and INRI written kabalistically; and in the monogram of Christ as embroidered on the Labarum, which the Kabalist Postel interprets by the word ROTA, whence the adepts have formed their Taro or Tarot, by the repetition of the first letter, thus indicating the circle, and suggesting that the word is read backwards (Transcendental Magic, Book 1, pp. 19-20).

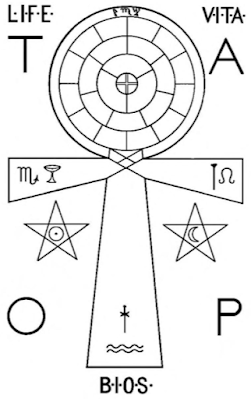

The above text is accompanied by the following illustration:

In the center we can see the Tetragrammaton -- God's name in Hebrew, usually rendered Jehovah or Yahweh in English -- flanked by INRI (for Iesus Nazarenus Rex Iudaeorum, "Jesus of Nazareth, King of the Jews") and by a variant of the Labarum made up of the Greek letters TAPΩ, corresponding to the Latin TARO. (I don't know where we are supposed to see the word AZOTH.)

The Labarum of Constantine properly consists of the Greek letters XP (the first two letters of Χριστός, "Christ"), often accompanied by A and Ω ("Alpha and Omega" being a title applied to Christ in the book of Revelation). Lévi's variant, with T instead of X, can hardly be called "the monogram of Christ," but it turns out to be a genuine Christian symbol, known as the staurogram because it was originally used to abbreviate the Greek word σταυρός, "cross" -- shortened to στρός, with the T and P written as a ligature. Like the XP ligature of the Labarum, the TP ligature was later often accompanied by A and Ω. The image below was found on a Catholic website having nothing to do with Lévi or the Tarot.

With only a single T, this gives us

taro -- the root vegetable, not the card game. This is where Lévi is, as he indicates, indebted to Guillaume Postel, who in his

Key of Things Kept Secret from the Foundation of the World described a complicated symbol which involved writing the word ROTA (and HOMO, and DEUS, and various other things) around the circumference of a circle. Lévi noticed that when ROTA is thus written, one could just as well begin with the T as the R and read TARO, after which we would arrive again at the T, giving us TAROT. (Despite what Lévi implies, Postel himself did not connect his ROTA with either the staurogram or the Tarot. See details

here.)

Incidentally, the staurogram, with A on the left, Ω on the right, and P at the top, sheds some light on something that has perplexed me for a long time: the letters on the cruciform halo of the Maiestas Domini image at the Basilique Saint-Sernin de Toulouse (a sculpture I discuss extensively in my post on

the World card). Cruciform halos generally bear the letters Ὁ ὬΝ ("the existing one"), but this one -- uniquely, so far as I know, and I've looked at a

lot of Maiestas Domini images -- bears the letters A, Ω, and R -- a strange mixture of the Greek and Latin alphabets.

|

| Letters enlarged for clarity |

Now I assume that the halo is based on the staurogram, with the cross itself representing T. The P has been Latinized as R, but the Ω has not; its significance is that it is the last letter of the alphabet ("Alpha and Omega, the beginning and the end"), so changing it to O is out of the question. It is interesting that this particular Maiestas Domini, which I consider to have been uniquely influential in the development of the Tarot, should (also uniquely) include the letters TARΩ in its design.

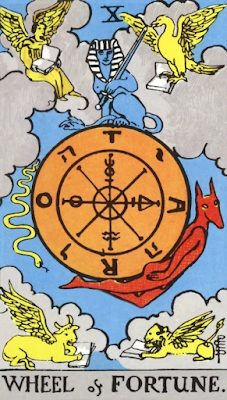

Lévi's La clef des grands mystères contains this representation of the Wheel of Fortune.

Aleister Crowley's English translation of the Clef adds a note describing the figure thus:

It is a type of the Wheel of Fortune. The wheel itself is erected on a wooden post, and has a crank affixed to the hub. There is no image of Fortuna to turn it. The base of the post is held by a blunt double crescent on the ground, rounded horns slightly up and in parallel like a hot-dog bun. Two nosed serpents issue from the base, cross once and arch toward the post just below the wheel. The wheel is double, having an outer and an inner ring with eight spokes running through both rims. The spokes have a circular expansion with central hole inside and a bit short of the inner rim. These spokes appear to be riveted to the inner rim. At the top of the wheel is the Nemesis seated on a platform as a sphinx with a sword: head cloth, stern male face and woman’s breasts, winged. The sword is hilt to wheel and up to left. 'ARCHEE' is written over the wing to the left. Rising on the right of the wheel is a Hermanubis or variation of Serapis: Dog’s head, human body, carries a caduceus half hidden behind head and wheel, legs before wheel. 'AZOTH' is written above the head of this figure. A demon reminiscent of Proteus descends the wheel on the left. His head is bearded and horned, his legs are tentacular and finned. He carries a trident below. 'HYLE' is written below his head.

Hyle of course means "matter," while

Archée (

Archeus) and

Azoth are alchemical terms.

Archée is defined at

this site (in French) as "the immaterial principle of organic life, different from the intelligent soul" -- in other words, something like what is normally called an "astral body."

Azoth, which normally refers to the element mercury, is used by Lévi to refer to "the Universal Magical Agent" or "Universal Medicine,"which he explains as follows: "The Azoth or Universal Medicine is, for the soul, supreme reason and absolute justice; for the mind, it is mathematical and practical truth; for the body it is the quintessence, which is a combination of gold and light. In the superior or spiritual world, it is the First Matter of the Great Work, the source of the enthusiasm and activity of the alchemist. In the intermediate or mental world, it is intelligence and industry. In the inferior or material world, it is physical labor." In other words, it can be just about anything, and the precise nature of its relationship to matter and to Archeus is unclear.

It terms of its apparent influence on Waite, the important things to notice about this image are: (1) the striped Egyptian headdress on the sphinx, replacing the traditional crown; (2) the dog-headed man Hermanubis, replacing the dog; and (3) in place of the monkey, a bearded demon with "tentacular" legs, connected by Crowley with Proteus but equally resembling traditional representations of Typhon.

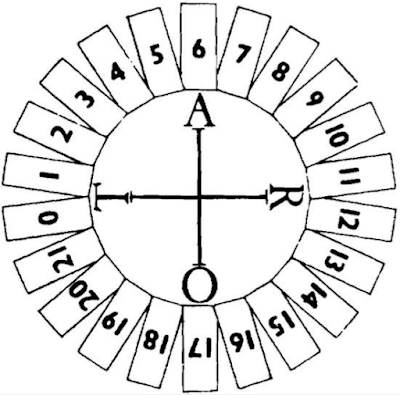

Waite was influenced even more directly by the treatment of the Wheel in The Magical Ritual of the Sanctum Regnum, "translated from the MSS of Éliphaz Lévi and edited by W. Wynn Westcott, M.B., Magus of the Rosicrucian Society of England" and published after Lévi's death, in 1896. It features illustrations which are "facsimile copies of Lévi's own drawings," and there are notes in Westcott's own voice at the end of each chapter. The illustration we are interested in is this one, accompanying a chapter which is called "The Wheel of Fortune" but actually discusses only the "Wheel of Ezekiel."

Again we have an eight-spoked wheel, and the word ROTA/TARO is written along its circumference, interspersed with cursive writing not notable for its legibility. (Reading clockwise from the top, I believe it reads "T électricité A chaleur R magnétisme O lumière" -- meaning, as I suppose is fairly obvious, "electricity, heat, magnetism, light." It is not clear what these terms, borrowed from physics, have to do with anything.)

I would have rotated the word 180 degrees, with R at the top, O on the right, T at the bottom, and A on the left -- corresponding to the orientation of the staurogram and of the Saint-Sernin sculpture. This orientation would also make ROTA the most natural reading, with TARO as a hidden second meaning, rather than the reverse. Furthermore, the letter A, turned so that its point is to the left, exactly resembles the Phoenician aleph -- which means "ox" and thus corresponds to the ox which occupies that position on the Wheel.

The design also features the four letters of the Tetragrammaton and the four living creatures of Ezekiel. (The living creatures are arranged according to the vision of Ezekiel and the camp of Israel, rather than in the astrological arrangement commonly used in the World card. See details

here.) The other characters on the Wheel are alchemical symbols, three of which represent the

tria prima of Paracelsus: sulfur, mercury, and salt.

These are the three primes, but the Wheel design calls for a fourth -- so Lévi, for reasons I do not pretend to understand, chose the astrological sign for Aquarius, sometimes used in alchemy to represent water, though an inverted triangle is more usual. I am also unsure as to why the sulfur glyph has been rotated 90 degrees but the one for salt has not.

Westcott's notes, appended to Lévi's text on the Wheel of Ezekiel, describe the card in question as follows: "The Tarot Trump marked 10 is named the Wheel of Fortune; the card shows a wheel supported on two upright beams. Hermanubis stands on one side, and Typhon on the other; above is the Sphynx holding a sword in its Lion's jaws. [. . .] This key is figured by Lévi in his Clef des grands mystères, page 117."

Although he references the illustration in the Clef, reproduced above, Westcott's description differs in several particulars from the published version of that illustration. He describes the wheel being supported on two beams rather than one, says the figures on the sides are standing beside the wheel rather than clinging to it, and has the sphinx holding a sword in its jaws rather than its hand. (This last is particularly strange, since human-headed sphinxes don't generally have lion's jaws! He must have meant to write "claws.") He also identifies the Hyle figure as Typhon rather than Proteus, an identification Waite would later follow.