Disclaimer: My terms are borrowed (by way of Terry Boardman and Bruce Charlton) from Rudolf Steiner, but I cannot claim to be using them in anything like a strictly Steinerian sense. In fact I have read only a tiny fraction of Steiner's voluminous output and assimilated only a tiny fraction of that. However, his demonology has long since taken on a life of its own.

These are just some tentative notes. I neither pretend nor aspire to be an expert on evil.

⁂

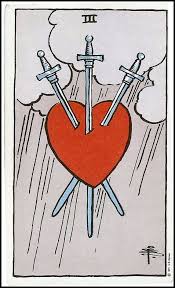

Sorath

MEPHISTO:

I am the spirit that negates.

And rightly so, for all that comes to be

Deserves to perish wretchedly;

'Twere better nothing would begin.

Thus everything that your terms, sin,

Destruction, evil represent—

That is my proper element.

-- Goethe's Faust (Walter Kaufmann's translation)

By Sorath I mean the principle of evil at its purest, the devil of all devils, Goethe's "spirit that negates." God is the love-motivated Creator, and Sorath is the hate-motivated anti-Creator, who opposes all creation -- who thinks it "better nothing would begin" and that all that has begun "deserves to perish wretchedly."

Sorath's ultimate goal is that nothing at all exist, including Sorath himself. Does Sorath exist, then? Perhaps not. Perhaps it is not possible that he should. It may be possible to be God, even to be Lucifer, but not to be Sorath. After all, who can fail to see the self-contradictory nature of the statement, "I am the spirit that negates"? Sorath should probably not be thought of as a person at all, but as the hypothetical limit to which evil converges. Appropriately, Sorath is not a name from folklore, not a demon people are actually said to have interacted with, but an artificial creation of Steiner's, made from the Hebrew numerals for 666.

God is, ultimately, a Person -- and, pace Yeats, there is no Deus Inversus, no equal and opposite God of Evil, no Angra Mainyu ("Ahriman" in the original Zoroastrian, non-Steiner sense of that name). Devils who are persons certainly exist, but the devil of all devils is an abstraction, a mathematical limit which none of them can quite reach. And the name we give to this limit, this outer darkness, is also mathematical: Sorath.

We may nevertheless speak, and not altogether figuratively, of "what Sorath wants" and what it means to "serve Sorath."

⁂

What Sorath is up against

Sorath is against creation and against Creator -- that is, against existence, against being as such -- so any understanding of Sorath's battle plan must begin with answering that ever-popular question, Why is there something rather than nothing? (And, yes, I intend to answer that little question en passant and then forge ahead with my demonology. This attitude is, incidentally, why there is something rather than nothing posted on this blog.)

Descartes, meet Berkeley. Berkeley, Descartes. Let's have each of you chuck your most famous Latin catchphrase into this here crucible and see what comes out, shall we? And . . . splendid: Esse est cogitari aut cogitare. "To be is to be thought, or to think." Sorath's enemies are thinkers -- God, the gods, and such humbler beings as ourselves -- and the combined harmonious thought of these thinkers, which is the creative Logos.

New thinkers

think themselves into existence, oh, probably all the time -- beginning as "minor presences, riffraff of consciousness" (Iris Murdoch's phrase) and then, some of them, developing from there, some even to the threshold of Godhood itself.

But this is likely a one-way street. Thinkers don't ever think themselves out of existence -- how could they? How could you cease, by an act of will, to have an active will? To say, or think, "I will my own annihilation," you have to say I will. Existence cannot be undone.

Thinkers -- excepting perhaps those dragons and titans and hecatoncheires who came into being before there was a Logos -- have a natural tendency to think and act in harmony with the Logos. At first, at the most rudimentary levels of development, this tendency is almost wholly passive and unconscious. "For behold, the dust of the earth moveth hither and thither . . . at the command of our great and everlasting God" (Hel. 12:8) and "even the wind and the sea obey him" (Mark 4:41).

As a thinker develops, though, and becomes increasingly active and conscious, the possibility of deliberately rebelling against the Logos begins to emerge. Sorath wants to persuade as many as possible to choose that path, with the ultimate goal of undoing creation, reducing the cosmos, if not to nothing at all, at least to chaos.

The problem, though, is how to persuade anyone to join you when you have quite literally nothing to offer. The devil of all devils wants everyone "to choose captivity and death, . . . that all men might be miserable like unto himself" (2 Ne. 2:27). Uh, what's the selling point again?

Ultimately, many can and will choose just that -- will say, "Evil, be thou my good!" and walk willingly into hell -- but they must be brought to that point by a circuitous route. That's where Lucifer and Ahriman come in.

⁂

Lucifer

In

The Song of the Strange Ascetic (which I discuss

here), G. K. Chesterton imagines how he would have lived if he "had been a Heathen" and expresses bafflement at the choice of an actual heathen called Higgins -- a sort of Caspar Milquetoast of heathenism -- not to live that life. Heathenism, we are to infer, is as much wasted on the heathens as youth is on the young.

A heathen Chesterton would have filled his life with wine, love affairs, dancing girls, and glorious military campaigns against the Chieftains of the North. He would have served Lucifer, in other words -- pursued forbidden pleasures -- and doesn't quite get this Ahriman fellow whom the prissy bourgeois Higgins chooses to serve instead.

Lucifer is all about wine, women, and song. Those who follow Lucifer are motivated by pleasure rather than the avoidance of pain, and are willing to embrace risk, danger, adventure, even a sort of heroism, in its pursuit. They do not shy away from violence and may even revel in it. Alcibiades, Casanova, Blackbeard -- Falstaff, even. (Not Epicurus, who, despite the modern connotation of his name, was a consummate Higgins.) This is the most relatable and accessible form of evil, the sort a good man like Chesterton could easily fantasize about embracing. "Gateway drug" is the term, I believe.

Why call this aspect of evil Lucifer? Well, because Steiner did, obviously, but we can also invent an ex post facto etymology for it. Lucifer, "light-bearer," is from the Latin lux, "light," but we can imagine that it derives instead from luxus, "luxury, debauchery." Also, Lucifer was originally a name for the planet Venus -- whose other name is that of the ancient Roman goddess of sex, drugs, and rock-'n'-roll.

⁂

Ahriman

How did Satan become Satan? Joseph Smith, the Prophet, proposes a somewhat novel origin story for this supervillain: One of the angels comes before the Lord and proposes, "send me, . . . and I will redeem all mankind, that one soul shall not be lost." And it is for this offer of universal salvation -- because, that is, he "sought to destroy the agency of man" -- that he is cast out of heaven and becomes the devil (see Moses 4:1-4).

If Lucifer seeks pleasure, Ahriman seeks

control. Note that this is not necessarily the same thing as seeking power. Those who serve Ahriman may seek to be

in control themselves, but more often their goal may simply be that everything be

under control. Hierarchy is of Ahriman, because even those who are far from the top have no objection to it. Even an Ahrimanist who has the ability to control things personally will generally defer these personal decisions to a system or algorithm, personal responsibility being unpleasantly risky. A near-perfect example of Ahrimanic man is the 2020s birdemicist, happy to submit to house arrest, universal surveillance and censorship, and forced medical procedures -- rather than take a chance of catching the flu. "Non serviam" is Lucifer's motto, not Ahriman's; if Ahrimanism were condensed into a two-word motto, it would be, "Safety first" -- or, if more than two words are needed, "

None are safe until all are safe" ("that one soul shall not be lost").

Lucifer's motivation is positive: the pursuit of pleasure. Ahriman's is negative: the elimination of risk. Lucifer's focus is personal; Ahriman's, universal. Thus Ahriman, though less obviously "evil" than Lucifer, is actually considerably closer than Lucifer to Sorath, to the pure and universal "spirit that negates."

Suicide has cause and stillbirth, logic; and cancer, simple as a flower, blooms.

-- Karl Shapiro

Conceptually, Sorath is primary, and I have discussed him first. Chronologically, in the evolutionary development of evil, he comes last. The natural progression is from Good to Luciferic, from Luciferic to Ahrimanic, and from Ahrimanic to Sorathic.

First, the good are tempted by forbidden pleasures, and by forbidden means of pursuing good ends, and embrace the ethos of Abbey of Thélème: Fay ce que vouldras, "Do what you want."

This Luciferic playing-with-fire leads to predictable results, people begin to feel that the world has become a chaotic and dangerous place, and they turn to Ahriman. We can see a clear example of this if we look back at the past half-century: As the flower children (those fleurs de mal) blossomed into flower fogeys, a movement that began with free speech, free love, and letting it all hang out evolved organically into the world of PC, sexual harassment prevention training, and a superstitious horror of the "inappropriate."

As Ahriman drains the world of its charm and turns everything into management and bureaucracy, as he extinguishes joy and the memory of joy, as everyone, to one degree or another, is assimilated into his soulless system, mutual respect becomes impossible, more and more people live in a state of barely suppressed rage, and the prospect of burning everything to the ground becomes increasingly attractive. Sorath has arrived.

⁂

The Blood War

When Sin claps his broad wings over the battle,

And sails rejoicing in the flood of Death;

When souls are torn to everlasting fire,

And fiends of Hell rejoice upon the slain,

O who can stand?

-- William Blake

In the Dungeons and Dragons cosmology, one of the defining features of the "Lower Planes" (hell) is the Blood War -- the interminable conflict between the chaotic-evil (Luciferic) demons and the lawful-evil (Ahrimanic) devils, with a third class of neutral-evil (Sorathic?) fiends manipulatively playing each side against the other. So -- did the D&D guys get hell more or less right? Was old Gary Gygax privy to one or two of the deep things of Satan?

If the Blood War did not exist, Sorath would have to invent it. Remember what Sorath wants -- for men to hate the good as such and to pursue evil strictly for the evulz -- and how contrary to human nature that is. How to get us humans to sail against the wind of our own deepest nature? By tacking, of course.

- Sorath's goal: Avoid good, pursue evil

- Human nature: Pursue good, avoid evil

- Lucifer tack: Sacrifice the avoidance of evil in order to pursue good (e.g. to seek pleasure)

- Ahriman tack: Sacrifice the pursuit of good in order to avoid evil (e.g. to be "safe")

Clever little devil, right? But so far this is just tacking, and no one ever said tacking was hell. War is hell. That's the next step. Notice that the Lucifer tack and the Ahriman tack are polar opposites and are both evil. With just a bit of nudging, we get this:

- Sorathized Lucifer: Sacrifice the avoidance of evil in order to destroy Ahriman!

- Sorathized Ahriman: Sacrifice the pursuit of good in order to crush Lucifer!

Rage against the machine! Machinate against the rage! Behead those who insult Sorath -- who, for his part, claps his broad wings above the battle and sails rejoicing in the flood of Death. O who can stand?

And he called them unto him, and said unto them in parables, "How can Satan cast out Satan? And if a kingdom be divided against itself, that kingdom cannot stand. And if a house be divided against itself, that house cannot stand. And if Satan rise up against himself, and be divided, he cannot stand, but hath an end.

Given what we have discussed thus far, what are we to make of this statement attributed to Jesus?

Victor Hugo's unfinished poem does not really address the matter; I have pilfered the title because of its ambiguity. La fin de Satan could mean the annihilation of Satan, or it could mean Satan's objective, his telos (which is in fact the word used in Mark) -- and, wait, are those even two different things? Didn't we say that "Sorath's ultimate goal is that nothing at all exist, including Sorath himself"? La fin de Satan est la fin de Satan.

Jesus, in the passage quoted, is responding to the claim that "by the prince of the devils casteth he out devils." The implication is that devils obviously don't work that way, because if they did, the whole enterprise of devilry would have collapsed long ago, torn apart by infighting. The continued existence of Satan is proof that Satan is not in the habit of undermining himself, and thus that the whole idea of a power-of-Satan-compels-you exorcist is inherently implausible.

Everything I've written in this post thus far -- Lucifer vs. Ahriman, the Blood War, all that -- seems to be saying that the kingdom of Satan succeeds by being divided against itself, and thus that Jesus was wrong. Well, as a Christian, I obviously can't leave it at that!

The easy way out would be to point out that this quote from Jesus does not appear in the Fourth and most authoritative Gospel, that Mark consists of notes compiled by a non-witness, and that Jesus may well never have said anything like this. Honestly, though, it sounds quite Jesusy to me, and I believe he probably did say it or something like it.

Another possibility is that Jesus was speaking specifically about exorcism. Back when I still believed the mainstream idea that Mark's was the most trustworthy Gospel and was focusing my studies on it, I went so far as to read an entire book called Demonic Possession in the New Testament, by William Menzies Alexander. Alexander draws a distinction between possession by "demons" or "unclean spirits" (a condition cured by Jesus on many occasions) and possession by "Satan" (attributed only to Judas Iscariot). The latter (which also has the distinction of being the only "possession" mentioned in the Fourth Gospel) is clearly moral in nature and leads to damnation. In contrast, those troubled by "unclean spirits" are treated as victims who bear no moral responsibility for their condition. The other important point that Alexander makes is that the wave of demon-possession described in Mark was a unique phenomenon, localized in time and space. With a few ambiguous exceptions like the case of King Saul, there is scarcely a hint of demon-possession in the Old Testament, nor does demon-possession in the Marcan mold appear to happen much in the modern world. (Satan-possession, in contrast, seems to be at an all-time high.) The demoniacs of first-century Palestine, a bit like the Convulsionnaires of Saint-Médard centuries later, appear to have represented a sort of spiritual outbreak or epidemic which flared up, spread through the population, and then burnt itself out -- with this last process perhaps expedited by the activity of Jesus and his disciples. If this phenomenon was the "Satan" Jesus' accusers were referring to, it would appear that its kingdom didn't stand, and it did have an end.

Something else to keep in mind is that Jesus' responses to critics or those who tried to catch him in his words generally worked on two levels. At the level of mere repartee, their purpose was to pwn and silence his opponents; at a deeper level, they were "parables" -- riddles -- conveying more substantive truth. For example, Jesus' famous statement about the unforgivable sin against the Holy Ghost was also a response to accusations that he used demonic power to cast out demons. As rhetoric, its message was, "Be very careful calling something demonic which may actually be from the Holy Ghost" -- but we can hardly conclude that mistakenly thinking a particular "miracle" may be demonic is the unforgivable sin! The deeper meaning of this statement is, well, deep, and a great deal has been thought and written about it -- almost all of which, rightly, departs from the statement's original rhetorical context.

So focusing too much on the conclusion "and therefore exorcisms are never performed by demonic power" may be much too narrow a constraint when it comes to understanding the deeper meaning of "How can Satan cast out Satan?" Rhetorically, it is supposed to work as a reductio ad absurbum: Satan obviously wouldn't undermine his own power; therefore, no exorcist is a servant of Satan. But those who think it out realize at that what it reduces to isn't absurd at all:

Satan cannot stand, but hath an end. I mean, what's the alternative, really? That Satan and his works will endure forever? That Satan --

ce monstre délicat -- has eternal life?

⁂

What if they gave a Blood War and nobody came?

But I say unto you, That ye resist not evil.

Yet Michael the archangel, when contending with the devil, . . . durst not bring against him a railing accusation, but said, "The Lord rebuke thee."

-- Jude 9

Jesus answered, "My kingdom is not of this world: if my kingdom were of this world, then would my servants fight."

But Jesus said unto him, "Follow me; and let the dead bury their dead."

We are not here to fight in the Blood War. We are not here to contend against Satan and those who serve him. The example of the Messiah conspicuously not overthrowing the Empire should have made that clear enough. We are here to learn, to serve God, and to follow Jesus to eternal life. Anything else is a distraction.