Tam multa, ut puta genera linguarum sunt in hoc mundo: et nihil sine voce est.

Sunday, May 2, 2021

Retracing the development of the Luciferic/Ahrimanic/Ahuric/Devic model

Monday, April 19, 2021

Lucifer, Ahriman, and Ganymede virtue sets

Rudolf Steiner saw Lucifer, Ahriman, and the Christ in Aristotelian terms: Lucifer is one extreme; Ahriman, the other; and the Christ represents the perfectly balanced "golden mean" between the two. This corresponds to the virtue theory propounded in the Nicomachean Ethics -- where, for example, Courage is seen as a golden mean between the extremes of Cowardice and Rashness.

It is wrong to conceptualize the Christ this way -- as if the goodness of God consisted in being just Ahrimanic enough without being too Ahrimanic -- as if Lucifer were 0, Ahriman were 1, and the Christ were 0.618... (realized to infinite decimal places in the Christ himself, but only approximated by mere mortals!). "Moderation in all things" is a Greek maxim, not a Christian one. The Christian version is this: "I would thou wert cold or hot. So then because thou art lukewarm, and neither cold nor hot, I will spue thee out of my mouth" (Rev. 3:15-16).

As I pointed out in my post "Vice and vice versa," Aristotle's one-dimensional theory of virtue is also an inadequate conceptualization of evil. It is quite possible to be simultaneously cowardly and rash -- it has in fact been the norm since 2020 -- but there is no Aristotelian way to model that. I recommended as an improvement the Ganymede virtue set (GVS) as pioneered by "G" of the Junior Ganymede blog.

A two-dimensional GVS consists of two virtues and two vices (whereas a one-dimensional Aristotelian virtue set, or AVS, has only one virtue per two vices). Cowardice and Rashness are not opposites; Cowardice is the opposite of Courage, and Rashness is the opposite of Prudence. Cowardice and Rashness are complementary (not opposite) vices, and Courage and Prudence are complementary virtues. It is (as we see every day now) possible to be both extremely cowardly and extremely rash. And it is possible to be (like the Christ?) both perfectly courageous and perfectly prudent. To quote G himself, referring to a slightly different virtue set, "Confident Humility sounds like a contradiction. So does Arrogant Timidity. But they are common enough that they are almost archetypes."

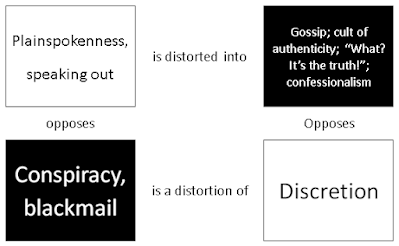

In the GVS diagram above, it is clear that one of the vices (Rashness) is Luciferic, and the other (Cowardice) is Ahrimanic. Is that a general rule? Here are some more GVS diagrams from G (taken from "Charting Virtue" and the other posts linked therein, to which the reader is referred for more details on these particular virtue sets).

- Luciferic vices: Rashness, immodesty, pride, "authenticity," "being true to yourself," the god within, gossip, "What? It's the truth!", confessionalism, rebellion, avant-gardism, high time preference

- Anti-Luciferic virtues: Prudence, modesty, humility, the "nameless virtue" of which hypocrisy is a distortion, discretion, obedience

- Ahrimanic vices: Cowardice, uglification, despair, contemptibleness, hypocrisy, conspiracy, blackmail, legalism, Pharisaism, fear, timidity

- Anti-Ahrimanic virtues: Courage, comeliness, glory, sincerity, plainspokenness, speaking out, breaking the letter to keep the spirit, trusting God to provide

Friday, December 4, 2020

Vice and vice versa

Ace of Hearts

On the A page of Animalia , an Ace of Hearts is near a picture of a running man whom I interpreted as a reference to Arnold Schwarzenegger....

-

Following up on the idea that the pecked are no longer alone in their bodies , reader Ben Pratt has brought to my attention these remarks by...

-

1. The traditional Marseille layout Tarot de Marseille decks stick very closely to the following layout for the Bateleur's table. Based ...

-

Disclaimer: My terms are borrowed (by way of Terry Boardman and Bruce Charlton) from Rudolf Steiner, but I cannot claim to be using them in ...